May 12, 2015

“33 Days”, a long-lost memoir of escaping the Nazis and occupied France, finally published in its complete edition

by Dennis Johnson

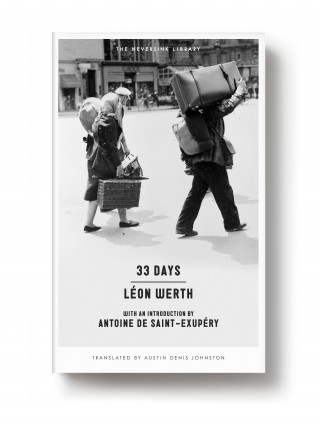

33 Days is based on a manuscript that was smuggled out of Nazi-occupied France in October of 1940 by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, who took it to New York with the intent of getting the book published in English. But the manuscript—which consisted of his friend Léon Werth’s firsthand account of his escape just months before from Nazi-occupied Paris, and an introduction to that account written by Saint-Exupéry—was never published, and subsequently vanished.

Fifty years later, in 1992, Werth’s French-language text was rediscovered and published by the French publisher Viviane Hamy. However that edition did not include Saint-Exupéry’s introduction, which remained lost. In 2014, the introduction was rediscovered in a Canadian library by Melville House, and thus this book represents not only the first English language edition of 33 Days, but the first edition of the book to include both the complete, original text and introduction, as originally intended by Werth and Saint-Exupéry.

Werth had asked Saint-Exupéry to smuggle the book out of France because, as a Jew, Werth was not allowed by the French government to publish anything. Forced to hide out in France’s Jura mountains and unable to move about as easily as his non-Jewish friend, Werth also no doubt felt, as did Saint-Exupéry, that an English-language version of his gripping, first-hand testimony might be useful to Saint-Exupéry in his greater mission in going to New York, which was to stir American support for intervention. After all, the story of the massive French flight from the approaching Nazi Werhmacht in May and June of 1940—a migration of such Biblical proportions as to now be called by historians “l’Exode,” or “The Exodus”—was largely unknown in the US. Werth’s account remains, in fact, one of the few eyewitness documentations of the Exodus, which is estimated to have involved over eight million people, and to have been the largest mass migration in human history.

In New York, Saint-Exupéry did manage to find an agreeable publisher, Brentano’s, a bookstore that during the war years also published French-language books in translation. Saint-Exupéry asked for nothing more than a military parcel consisting of chocolate, cigarettes, and water purification tablets in payment, and was so certain of the publication that he mentioned 33 Days in a book of his own published around that time, Pilote de guerre. However, for reasons that remain unknown, the book never appeared, and the manuscript was lost. Saint-Exupéry was apparently so frustrated by the failed publication that he took his introduction, at least, and expanded it into another wartime book, Letter to a Hostage, with the “hostage” being Werth—who goes unnamed for his protection.

While Werth would survive the war and go on to write numerous books, Saint-Exupéry would not, his plane disappearing while on a reconnaissance mission over the Mediterranean in July of 1944, presumably shot down by the Germans.

But 33 Days, in addition to being a vivid and harrowing first-person account of one of modern history’s major events, and a welcome introduction in English to an important French writer, stands as a testament to a long-term friendship tempered in wartime, that of Léon Werth and Antoine de Saint-Exupéry—who dedicated his most famous work, The Little Prince, to Werth:

“I ask children to forgive me for dedicating this book to a grown-up. I have a serious excuse: this grown-up is the best friend I have in the world… he lives in France, where he is hungry and cold. He needs to be comforted.”

Dennis Johnson is the founder of MobyLives, and the co-founder and co-publisher of Melville House.