August 14, 2015

Friday Popol Vuhs

by Melville House

This August, as we prepare to unleash a bunch of incredible books into the world, MobyLives will be taking a bit of a breather. We’ll still post the occasional news item or feature, but for most of this month we’ll be posting a roundup like this every morning. We will, of course, remain active on Twitter and Facebook. We hope you have a great August, and that you’ll keep checking in with us!

This August, as we prepare to unleash a bunch of incredible books into the world, MobyLives will be taking a bit of a breather. We’ll still post the occasional news item or feature, but for most of this month we’ll be posting a roundup like this every morning. We will, of course, remain active on Twitter and Facebook. We hope you have a great August, and that you’ll keep checking in with us!

- Central London will be home to 25,000 new books come October; Waterstones has announced it’s opening a new three story branch on Tottenham Court Road. (The Bookseller)

- “Books required!” There’s serious concern after Birmingham Libraries published a flyer requesting book donations from the public, reading “Due to public saving cuts we are no longer purchasing any new books or newspapers.” (The Guardian)

- President Obama‘s summer reading list includes Ta-Nehisi Coates‘ Between the World and Me, The Sixth Extinction by Elizabeth Kolbert, and The Lowland by Jhumpa Lahiri. (The Washington Post)

- Haruki Murakami‘s advice column has been collected into an 8-volume ebook. He answered 3,716 letters, but you’ll have to read them in Japanese; there’s no English version planned. (Entertainment Weekly)

- David Oyelowo is the first black James Bond. Sort of—he’s reading the audiobook, but would make an A+ Daniel Craig replacement.

- James McBride is writing a nonfiction book about James Brown. Chances are, it will be great. (Associated Press)

- The inaugural Galley Beggar Short Story launches this weekend. (The Bookseller)

- The world’s oldest multicolor book has been digitized, so you can look at it without it turning into a giant pile of old ass dust. (Smithsonian Magazine)

- The cover of the 20th anniversary edition of Infinite Jest will have a fan made cover. Cool. (Entertainment Weekly)

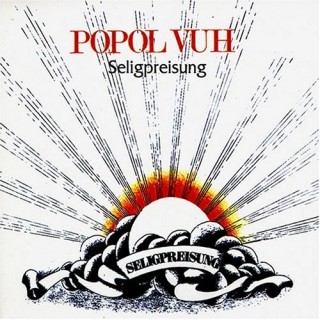

This month’s roundups are brought to you by Future Days: Krautrock and the Birth of a Revolutionary New Music. Each roundup will feature a short excerpt of the book, and a couple of songs from a Krautrock band. Today’s band is Popol Vuh.

Today’s excerpt from Future Days:

Formed in 1969, and with their leader Florian Fricke having managed to obtain a Moog synthesizer long before such instruments were available to his peers, Popol Vuh are understandably considered to be foundational to the Krautrock phenomenon. Born in the Bavarian island town of Lindau in 1944, he was introduced to the piano as a child. ‘I began to make music when I was eleven,’ he told Sandy Robertson of UK magazine Sounds in 1981. Among his tutors was the brother of the great twentieth-century composer Paul Hindemith. He would discover free jazz – throughout his life he would claim a spiritual kinship with John Coltrane’s contemporary Pharoah Sanders. He would also briefly hook up with Manfred Eicher, who later founded the ECM label, in a jazz-fusion combo. His head was further turned from his studies by his interest in film – one of his first paying jobs was as a film critic for Der Spiegel, among others.

He was also, inevitably, touched by the insurrectionary spirit of the era, but it was one aspect of that time in particular that affected him, as radical young Germans turned against their economic benefactors the Americans, revealed as imperialists by their involvement in Vietnam. As he told his friend Gerhard Augustin, to whom he granted a rare interview in 1996, ‘There was also a spiritual revolution. We have discovered the Eastern part of this globe.’ The epiphany he experienced when he came across the old Mayan book Popol Vuh (‘Book of the Community’, though the name was hand- picked for the difficulty of translating it precisely) hit home ‘like a thunderstorm’, he said.

Popol Vuh’s debut album, Affenstunde, which means something like ‘Monkey Hour’, was released in 1970. Its cover is, on the face of it, a quintessential hippie tableau. It sees Fricke, in sleeveless sheepskin top, attending to his Moog like a radio ham, as percussionist Holger Trülzsch sits swaddled in Afghan coating astride his drumskins while Bettina Fricke, Florian’s wife, who co-produced the album and designed the cover, attends to her tabla. Beginning with a simulation of birdsong, we are immediately plunged, as if through a black hole, into the outer reaches of uncharted space. Even today, it sounds otherworldly, beguiling, perhaps precisely because of its ‘datedness’, its raw technological naïveté a rarity in today’s world of ubiquitous, incidental electronic blare. A film student, Fricke would doubtless have recently seen Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. He spoke of Affenstunde as looking to ‘capture the moment when a human being becomes a human being and is no longer an ape’. There are reminders, as his Moog rears up from the mix, of the moment early on in the film in which the primates throw a bone in the air, only for a jump-cut to transform it into an orbiting spacecraft centuries hence.

For 1971’s In den Gärten Pharaos (‘In the Garden of Pharaohs’), Fricke and co. decamped to the Pilz label, set up that year by the notorious Krautrock entrepreneur Rolf-Ulrich Kaiser. It consisted of just two side-long tracks, with Fricke’s Moog again to the fore, supplemented by organ and piano. The opening title track com- mences in similar vein to Affenstunde – the distant sounds of bird- song and the lapping waters of a simulated landscape supplanted by the dark, billowing tones of synth, throbbing ghoulishly from every corner of the mix, ascending, descending, probing and over- lapping. Fricke has mastered his instrument, overcome some of its wobblier, patchier tendencies that were still entertainingly evident on the debut, while Trülzsch’s percussion is now rhythmically plundered from African and Turkish traditions, doing battle with the starry lights and meteoric runs of the Moog.

‘Vuh’, by contrast, recorded in the ecclesiastic setting of a church, is immediately a sterner proposition, as Fricke strikes up on an organ from high in the rafters, amid the theatrical shimmer of cymbals. The organ tones hang like a Gothic awning for several minutes with cathedral permanence, announcing them- selves over and over rather than embarking on the narrative of a solo, as percussion breaks out in rebellion now and again at the admonishing air of the track, before relapsing. In some ways, it prefigures the likes of Sun O))), whose metal is formally arranged into a ritual almost for ritual’s sake. ‘Vuh’ is a black mass of sorts, but containing no text, injunctions or dogma, merely structure and gravitas.

It was at this point, however, that Fricke made the decision to abandon his synthesizer altogether. For Hosianna Mantra, in 1972, there were wholesale changes. In came Conny Veit on electric and twelve-string guitar, Robert Eliscu on oboe, Klaus Wiese on tamboura and Fritz Sonnleitner on violin, while the Korean Djong Yun, daughter of a composer, took up vocals. For Popol Vuh fans, Hosianna Mantra is Fricke’s Everest, a masterpiece of quasi-religiosity in which East and West are straddled, as implied in the album’s title. ‘A high point in the history of music,’ insisted writer Gary Bearman in 2008.

—

Their soundtrack work for Werner Herzog was more than just jobbing day-work but a vital audio-visual collaboration. They seemed destined to meet – Herzog had further pricked Fricke’s interest by using the text of the Popol Vuh as the basis for one of the chapters of his 1971 movie Fata Morgana. Perhaps it’s precisely because of its antithetical nature that Popol Vuh’s music made for such an appropriate soundtrack to these films. It serves as a counterpoint, an ironic one.

Still more effective was Popol Vuh’s soundtrack for Nosferatu the Vampyre, released in 1979. Fricke provides pretty, string-soaked background for the pastoral scenes – however, his high Gothic strains also enhance the more beguilingly terrifying passages of the film. Each is accompanied by a simple but devastating two-note choral leitmotif from Fricke which, once heard, is never forgotten, and which helps engrave the key images from Herzog’s movie on the memory.

For those who find the late Fricke’s musings on spirituality somewhat conceptually vapid, the marriage of his music and Herzog’s content is one made in heaven.