January 5, 2016

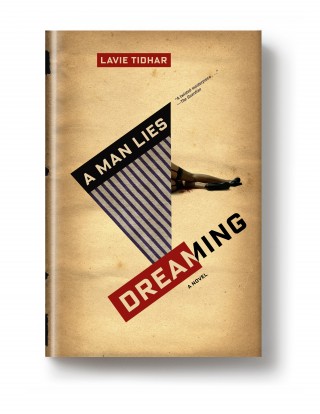

Spring Books Preview: A Man Lies Dreaming by Lavie Tidhar

by Mark Krotov

Over the next few days, we’ll be offering a peek at the titles we have lined up for Spring. Lavie Tidhar’s novel A Man Lies Dreaming is out March 8, 2016.

Over the next few days, we’ll be offering a peek at the titles we have lined up for Spring. Lavie Tidhar’s novel A Man Lies Dreaming is out March 8, 2016.

If you’re a Raymond Chandler fan, the opening pages of Lavie Tidhar’s A Man Lies Dreaming will prove a source of considerable excitement. Here are the master’s exquisite, obsessive descriptions; the shadowy urban landscapes; and of course, the stern, gloomy private investigator who sees trouble everywhere. But things soon start to get weird. For one thing, we’re in London, not Los Angeles. And Wolf, our would-be Marlowe, seems to have had quite a political past before he ended up as London’s most miserable PI. And wait, come to think of it, Wolf looks and sounds an awful lot like . . .

Nope, sorry, it’s too good a twist to give it away. But suffice it to say that A Man Lies Dreaming is much more than a perfectly pitched neo-noir. It is, instead, a radical and provocative and wholly new kind of Holocaust novel—breathtaking in its audacity, its boldness, its holy-shit-how-did-he-just-pull-that-offness. Tidhar will make you laugh when you’re not supposed to, and he’ll leave you devastated you when you least expect it. The Guardian called A Man Lies Dreaming a “twisted masterpiece,” and it’s certainly that. But above all, it’s that rarest of things: a true original.

She had the face of an intelligent Jewess.

She came into my office and stood in the doorway though there was nothing hesitant about the way she stood. She gave you the impression she had never hesitated a moment in her life. She had long black hair and long pale legs and she wore a summer dress despite the cold and a fur coat over the dress. She carried a purse. It was hand-threaded with beads that formed into the image of a mockingbird. It was French, and expensive. Her gaze passed over the office, taking in the small dirty window that no one ever cleaned, the old pine hatstand on which the varnish was badly chipping, the watercolour on the wall and the single bookshelf and the desk with the typewriter on it. There wasn’t much else to look at. Then her gaze settled on me.

Her eyes were grey. She said, ‘You are Herr Wolf, the detective?’

She spoke German with a native Berliner’s accent.

‘That’s the name on the door,’ I said. I looked her up and down. She was a tall drink of pale milk. She said, ‘My name is Isabella Rubinstein.’

Her eyes changed when she looked at me. I had seen that look before. In her eyes clouds gathered over a grey sea. Doubt – as though trying to place me.

‘I’ll save you the trouble,’ I said. ‘I am nobody.’

She smiled at me. ‘Everyone is somebody.’

‘And I do not work for Jews.’

At that the clouds amassed in her eyes and stayed there but she remained calm, very calm. Her hand swept over the room. ‘I do not see that you have so much choice,’ she said.

‘What I choose to do is my own damn business,’ I said.

She reached into her handbag and came back with a roll of ten-shilling notes. She just held it there, for a long moment.

‘What is it about?’ I said. At that moment I hated her, and that hatred gave me pause.

‘My sister,’ she said. ‘She is missing.’

I had two chairs for visitors. She pulled one to her and sat down, crossing one leg over the other. She was still holding the notes between her fingers. She didn’t wear any rings.

‘A lot of people are missing nowadays,’ I said. ‘If she is in Germany I cannot help you.’

‘No,’ she said, and this time there was tension in her voice. ‘She was leaving Germany. Herr Wolf, let me explain to you. My family is very wealthy. After the Fall our assets were seized, but my father still had friends, some even amongst the Party, and he was able to transfer much of our capital to London. I myself, and my mother, were both allowed to leave the country legally, and my uncles continue the family’s continental operations in Paris. Only my sister remained behind. She is young, younger than me. At first she was beguiled by their ideology; she had joined the Free Socialist Youth before the Fall. My father was furious. But I knew it would not last.’ She looked up at me, with a half-smile. ‘It never does, with Judith, you see.’

All I could see was the money she was holding between those long slim fingers. She moved the roll of notes back and forth, idly. I had been penniless before, and poverty had made me stronger, not weak, but that was in my former life. My life was different now, and it was harder to be hungry.

I said, ‘So you arranged for her to leave.’

‘My father,’ she said quickly. ‘He knew men who could smuggle people out.’

‘Not easily,’ I said.

‘Not easily, no. Not cheaply, either.’ Again that half-smile, but it flickered and was gone in a flash.

‘How long ago was that?’

‘A month. She was meant to be here three weeks ago. She never appeared.’

‘Do you know who these men were? Do you trust them?’

‘My father did. As much as he could be said to trust anyone.’

Something jogged my recall, then. ‘Your father is Julius Rubinstein? The banker.’

‘Yes.’

I remembered his likeness in the Daily Mail. One of the Jewish gangsters who grew rich and fat on the blood of the working man in Germany, before the Fall. His like always survived, like rats abandoning a sinking ship they fled Germany and re-established themselves elsewhere, in clumps of diseased colonies. They said he was as ruthless as a Rothschild.

‘Not a man to cross,’ I said.

‘No.’

‘Your sister . . . Judith? She could have been captured by the Communists.’

She shook her head. ‘We would have heard.’

‘You think she was brought to London?’

‘I don’t know. I need to find her. I must find her, Herr Wolf.’

She put the roll of notes on my desk. I left it there, though whenever I looked at her the notes were in my field of vision. The Jews are nothing but money-grubbers, living on the profits of war. Perhaps she could see it in my eyes. Perhaps she was desperate. ‘Why me?’

‘The men who smuggled her here,’ she said, ‘are old comrades of yours.’

There was nothing behind her eyes, nothing but grey clouds. And I realised I had misjudged Fräulein Isabella Rubinstein. There was a reason she had picked me, after all.

‘I do not associate with the old comrades any more,’ I told her. ‘The past is the past.’

‘You’ve changed.’ She said that with curiosity.

‘You do not know me,’ I said. ‘Do not ever presume to think that you do!’

She shrugged, indifferent. She reached into her purse and brought out a silver cigarette case and a gold lighter. She opened the case with dextrous fingers and extracted a cigarette and put it between her lips. She offered me the open case. I shook my head. ‘I do not smoke,’ I said.

‘Do you mind if I do?’

I did mind and she could see it. She flicked the lighter to life and wrapped her half-smile around the cigarette and drew deep, and blew smoke into the cold air of my office. A draught came in through the window and though I was dressed in my coat I shivered. It was the only coat I owned. I looked at the money.

I looked at her face. She was nothing but trouble and I knew it and she knew I knew. I had no business hunting for missing Jews in London in the year of our Lord 1939. I once had faith, and a destiny, but I had lost both and I guess I’d never recovered either. All I could see was the money. I was so cold, and it was going to be a cold winter.

A Man Lies Dreaming by Lavie Tidhar

PAGES: 288

ISBN: 9781612195049

FORMAT: HARDCOVER

ON SALE MARCH 8, 2016

Mark Krotov is senior editor at Melville House.