November 30, 2015

“All novels should have songs” — Lars Iyer on writing

by Melville House

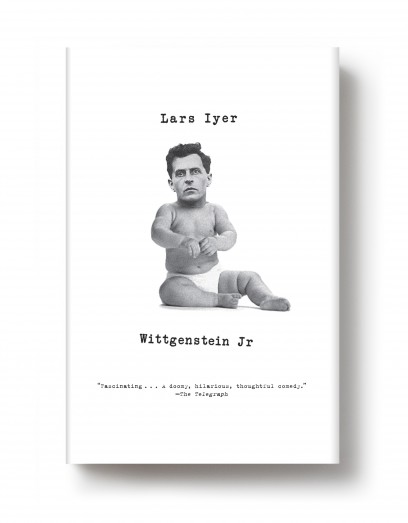

Last week, The Guardian asked Melville House author Lars Iyer where in the world his most recent, deliciously bizarre novel, Wittgenstein Jr, came from. Below, reprinted with the author’s permission, is his response …

Last week, The Guardian asked Melville House author Lars Iyer where in the world his most recent, deliciously bizarre novel, Wittgenstein Jr, came from. Below, reprinted with the author’s permission, is his response …

I like to write about philosophers in my fiction, but what a gloriously difficult subject philosophy is! EM Cioran asks: “How can a man be a philosopher? … How can he have the effrontery to contend with time, with beauty, with God, and the rest?” It’s a good question. Real philosophers — not to be confused with academic philosophers, with the philosophers of our contemporary university — feel a burning sense of vocation, but are never quite sure what they are being called to. They’re diagnosticians, symptomatologists. They’re working on a cure. They philosophise for the world, even if the world ignores them. It’s admirable, but also quixotic. It’s no surprise that they often have a sense of being against their times.

There are few philosophers who have felt the duty of philosophy more strongly than Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889-1951). My novel Wittgenstein Jr is indeed based on the life and myth of the great Viennese philosopher, which I find irresistible. But the novel is set in our present – in today’s Cambridge – and Wittgenstein is a nickname some students give to their intense young lecturer. It is a fitting nickname: my character is as afraid as the real Wittgenstein was of losing his mind. He has the same quasi-religious faith, initially at least, that his studies in logic might save him. He has immense personal charisma, inspiring acolytes and followers by his seriousness and integrity; and, like the real Wittgenstein, he comes into collision with university institutions, albeit for different reasons than his predecessor.

My character, Wittgenstein Jr, is particularly troubled by the figure of the contemporary don, who is more concerned with making research bids in the entrepreneurial culture of the contemporary university than with excelling as a scholar and teacher. He is horrified by the corporatism of the contemporary academic, interested in little other than gaming the new evaluation metrics and networking in enterprise zones and profit-driven research centres. He is also suspicious of old-style dons, and for the same reason that we might be today – their sense of common culture and shared endeavour, along with their soaring patriotism and moral purpose, were premised on entrenched privilege, on exclusions and subordinations based on class, gender, sexuality, religious background and ethnicity. The Wittgenstein of my novel has little patience with the values and ideals of what he calls the “English lawn”, and yet he nevertheless harks back to older models of association between academics, and between them and their students.

Until recently, your tutor at a great university was both a challenger and a goad, trying to push you to be better than you were. You could expect rebuke if you were not living up to your intellectual potential. Educo, the Latin root of education, means “I raise up” or “I lead forth”. Old-style dons sought to raise their students up, according to the old notion of Bildung, of formation, turning them towards higher ideals, lighting them on the road to full humanity. Wittgenstein Jr would like to raise his students up, but he finds them altogether free of that yearning for ideas, that infinite desire that is the condition of learning. And indeed, the students we meet in Wittgenstein Jr seem, initially at least, to be more interested in mischievous, pub modes of skiving off their studies – in seeking new ways of getting high, in staying up all night with a bottle of spirits between them – than in serious ideas and philosophical discussion.

For all this, the Wittgenstein of my novel is pushed towards a crisis that makes him change not only his view of philosophy, but also to come to appreciate his students for their very hedonism, for the way they can wildly enjoy life. In the end, they give him a clue as to how he might live once he is able to finish his treatise on logic. Might he one day idly doodle in the margins of Plato, and make paper boats from weighty philosophy tomes? Might he let himself fall in love? For their part, Wittgenstein Jr’s students come to appreciate their serious young lecturer, too, taking walks with him along Cambridge’s College Backs, driving him out to the countryside and hearing him speak on the many ills of the age.

In particular, Wittgenstein Jr becomes close to shy and unaffected Peters, the narrator of the novel and a scholarship boy from the provinces, who I modelled on the historical Wittgenstein’s real life friend David Pinsent. Like Pinsent, Peters is sweet and unselfconscious, and almost immune from the stormy moods from which his teacher suffers. And, like Pinsent, Peters writes a record of his time with his teacher. This is the book Wittgenstein Jr itself. The narrative is Peters’s act of love for his eccentric teacher, recording for posterity the struggles of a thinker at odds with his time.

As always in my fiction, there’s high despair and low humour. And there’s romance, too. And songs (all novels should have songs). There are quotes from Wallace Stevens, from Goethe, lines from Pretty Woman. And there’s utopianism – even a kind of messianic yearning, as Wittgenstein Jr dreams of a world liberated by philosophy and then liberated from philosophy, of a post-philosophical paradise, where a kind of innocence is regained and life can be led simply, without reflection, and seriousness is indistinguishable from play.