April 2, 2013

Boris Berezovsky in conversation with Anna Politkovskaya

by Alex Shephard

Russian oligarch Boris Berezovsky died in exile in London just over a week ago. Although examiners declared that Berezovsky’s death was “consistent with hanging and there were no signs of a violent struggle” police are not yet ruling out the possibility of foul play.But Berezovsky’s death was most likely the result of his much reduced circumstances: he was broke, isolated, and depressed—and police haven’t been shy about the fact that they believe he committed suicide.

Berezovsky is considered by many to be emblematic of Yeltsin-era Russia. He made his fortune by acquiring a wide variety of assets, most notably the country’s largest television network. While Berezovsky’s large fortune (around $3 billion at its height) attracted its share of attention, the methods by which Berezovsky made it were often more fascinating — he was, for a time, the poster-robber baron of Russian oligarchy and excess, and allegations of corruption and other criminal activities had dogged him for years before his death.

But in post-Soviet Russia, writes Masha Lipman in The New Yorker, “Berezovsky was the one-man powerhouse of national politics, one of the country’s richest tycoons, and the kingmaker behind Vladimir Putin’s ascent to the presidency in 2000.” However, shortly after Putin’s election, the two had a very public falling out. Berezovsky left the country six months later, never to return. He spent the next 13 years ensconced in London, where he made a new name for himself as one of the Kremlin’s fiercest critics. At times, he even advocated its overthrow, telling The Guardian in 2007 that “We need to use force to change this regime. It isn’t possible to change this regime through democratic means. There can be no change without force, pressure.” After gaining asylum in Britain he was tried twice in Russia in absentia, for crimes including embezzlement, money laundering, and fraud.

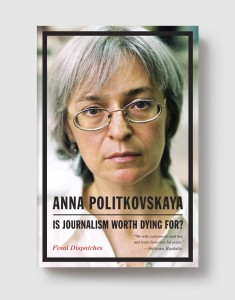

Famed Russian journalist Anna Politkovskaya interviewed Berezovsky in 2003. Her interview, accompanied by her introduction and afterword, are published below. The conversation was first published in the Russian newspaper Novaya Gazeta on January 20, 2003. The English translation is by Arch Tait and is excerpted from Politkovskaya’s Is Journalism Worth Dying For?: Final Dispatches, published by Melville House.

* * *

It is easy to insult an oligarch in exile but far less easy to understand one. Consider what he was in the past. The man who manipulated Yeltsin, the Mr Fix-it of Chechnya, the man who made a fortune out of oil, Zhiguli cars, and Aeroflot. And then it was the turn of Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin, Berezovsky’s most ambitious project. It was Berezovsky who backed Putin as the future of Russia, and so far he has lost hands down, which, admittedly, takes some of the sheen off his image as a demonic genius. It also makes him seem more human, what with the creature of his “Second President of Russia” project sitting comfortably in the Kremlin while Berezovsky is banished to the Lanesborough Hotel. Of course, this is a high-end hotel, in a top-of-the-range city, with Hyde Park outside his windows. Neither is he lonely; the Lanesborough is where the crème de la crème stay, and you can meet them in the foyer without their bodyguards. Oligarchs Deripaska, barefoot in jeans in the morning, Potanin, and Berezovsky with their wives and children. And there’s the Library Bar, the best place on the planet for the world’s Establishments past and present to relax. The armchairs in the library are just like the ones you aren’t allowed to sit on in the Hermitage, only here you are allowed to sit on them and even put your feet on them if you like. They are splendid, but all the same the Lanesborough is not the Kremlin.

Why did you choose Britain for your exile?

It was chance. I just happened to be here in October 2002 when I learned that the Prosecutor-General’s Office wanted to arrest me on an allegation of embezzling Aeroflot funds. That’s when I decided to stay, but that was not the only reason. I had lived in the south of France for a year but, in spite of the lush climate, I found it difficult to work there. The environment is debilitating. Britain is quite different. I find the climate here phenomenal and it suits me very well. The only thing I miss is the snow, but last week there was even some of that. It fell for the first time in 15 months—I felt quite at home. I have lived in France, Germany, and America, and can say without hesitation that if I had to choose somewhere to live other than Russia, then this is the most comfortable place to be. Another thing is London itself. The city is super-international. You are left in peace entirely, although at the same time you are not allowed to bother other people. In spite of all the difficulties of my situation––and I am a thorn in the flesh of the Russian Government––nobody has so much as hinted to me that I might not be welcome.

My status in Britain is rather unclear. I have not yet been granted permanent residence and have been waiting for the decision of the British Home Office for over a year, which is a bit disturbing. But imagine this situation in reverse: suppose I am a British citizen and a furious opponent of Blair (and I make no bones about the fact that I am conducting a campaign against the Russian authorities from here), and I am living in Russia; assuming Putin was on good terms with Blair, and Blair says, “Volodya, you have this character living in your country who is such a pain in my neck. Send him back to Britain, would you?” I have no doubt that the very next day, caged and in handcuffs, I would be on a plane back, because in Russia there is no justice and no protection of rights, and that goes not only for foreign citizens, but, for heaven’s sake, even for their own. Britain, in contrast, is a country where the law is tremendously respected. Another significant aspect is that nobody who is here now—Zakayev, Litvinenko—came here of their own free will. They would like to go back to Russia. America is 10 hours’ flying time from Russia. That’s a long way, and communications are difficult, while here you are living in the same information environment as Russia. People emigrate to America who don’t want ever to go back.

How do you see Europe’s current position on the Chechen crisis, after the Zakayev affair has put an end to the peace process which was developing in Europe through him? Does Europe really want to stop the war?

Let us first of all consider the place that events in Chechnya occupy among the political and social concerns of the West. We have to admit they do not have that high a priority. The British have plenty of problems of their own. Number 1 is Iraq and whether there is going to be a war there. But, more generally I would say attitudes have changed radically, and not in Russia’s favor. Serious matters such as the arrest of Zakayev have played a role in this, but also ephemeral things like Putin’s ill-judged remarks at a press conference in Brussels about circumcising a journalist who asked him about Chechnya. Sad to say, the fate of a human being like Zakayev and a stupid remark made by an uneducated man seem to carry roughly the same weight here in the scales of public opinion. The Brussels outburst was simply crude, and people here react strongly to primitive behaviour. For a long time in the West they were asking, “Who are you, Mr Putin?”, and now they think they have the answer.

These things coincided. The Zakayev affair infuriated Putin; he had lost the argument. Denmark’s decision outraged him. Headlines started appearing in the leading Western newspapers equating Putin with Miloševic. “Why should we accept Putin and roll out the red carpet for him when he is a state criminal?” Before the Zakayev affair you didn’t hear that kind of remark. Although European governments are forever trying to maintain good relations with Russia, which is understandable from a pragmatic viewpoint because they need Russia’s support in the impending war in Iraq, a chasm has suddenly opened up, between the logical behaviour of the upper echelons of European governments, and opposition politicians who have begun to criticize Putin and Russia harshly. There is also now a clear divide between the upper echelons and public opinion which, as a rule, is articulated by the press. The result is a change of attitude towards the Chechen War which may be important, although not decisive, for stopping it. That decision is one for the Russian Government to take. I would just like to quote what Zakayev once said: “Russia has the right to start a war with Chechnya, and it has the right to stop it.”

What do you mean by “important, although not decisive”?

Europe’s new position will seriously irritate the Russian Government, and push it towards a solution which will only result in its being constantly reminded of this irritant. Putin is very sensitive to personal attacks, and the terminology the West is adopting undermines him psychologically. He does not understand the real nature of the objections, and takes them personally. How the West reacts to Putin as an individual and his personal standing with the Russian public is one of the main sources of his power. After Brussels and Zakayev, the West is never going to view him as a friend because it sees that he does not share ideas which are fundamental to Western society. He does not believe in them, and in the West he is now considered a hypocrite.

The Zakayev incident was a fiasco. Zakayev is one of the most admirable figures in Chechnya. I have no hesitation in saying that. I know him not only from hearsay. I conducted extremely difficult negotiations in Chechnya, and never had any doubt that Zakayev wanted peace or that he was constructive in that respect. Zakayev’s role is plain for everyone in the West to see. There is not a single fact suggesting that he wishes to prolong the war, while there are many which testify to his having consistently defended the idea of a peaceful way out of this slaughter.

I consider that 2002 has been the most damaging year for Russia since 1991, when the Soviet Union collapsed. There aren’t enough fingers on one hand to list the defeats. The most important landmark is a qualitative change in the situation in Chechnya. If before 2002 I was sure that we could find a solution ourselves, negotiate peace between the belligerent sides, I consider that is now impossible. 2002 has been a watershed: the hatred on both sides has reached such heights that without international mediation – including involvement of countries outside the former Soviet bloc and the use of force – we can no longer resolve the conflict. This is Russia’s greatest setback. The country has lost its sovereignty in the sense that, without the intervention of external forces, it is incapable of settling its internal conflict. Russia has now suffered a devastating defeat in the Second Chechen War, considerably more serious than in the First, and the defeat is precisely that we have lost our sovereignty.

Russia’s second political defeat has been Kaliningrad [the Russian enclave between Poland and Lithuania]. We shouldn’t have gone on so foolishly and at such length, trying to tie everything down in terms of flight paths, access corridors and high-speed rail links. We should have approached the matter in terms of integration into Europe. We should have said, yes, we accept the option involving visas, but only so as to have guarantees that the whole of Russia will become part of Europe’s borderless Schengen zone within a specified number of years. This discussion never took place for the simple reason that for many centuries the Russian political elite has deeply mistrusted its own powers. Russia does not believe it is capable of taking a bet on what will happen in five or ten years’ time. Russia does not believe in its own strength. We want to be in Europe, but are afraid of that.

In the post-Soviet territories we have also suffered a complete rout. The Commonwealth of Independent States no longer exists as a unified political and economic community. That is a fait accompli. There are American troops in Central Asia and Georgia, the Baltic Region is in NATO. Relations with Belarus have only got worse. As regards more distant borders, the most striking example is Iraq. We are losing it. We took a serious step away from Iraq and lost political and economic influence in the region. I recollect the games played in 2002, manipulating a $40 billion co-operation deal as if it was just a game of “Now you see it, now you don’t.” The Kremlin is occupied by a bunch of sleight-of-hand spivs who think that if they tear up a $40 billion contract the Americans won’t invade Iraq, or will pay us back afterwards.

In addition, Russia has suffered a huge moral reverse. Most people in the West are increasingly coming to the view that Russia is not a democratic country. It is not following a liberal path, but exactly the opposite, destroying the fundamental mechanisms of democratic statehood.

Afterword

And that was all. On that note my tape ran out. It was time to come back to Moscow. It can happen that even demonic geniuses make mistakes, and if they get it wrong once then what guarantee is there that they will not get it wrong again? It has to be said, though, that however things actually turn out, people think devilishly freely in London. The Kremlin it isn’t.

Alex Shephard is the director of digital media for Melville House, and a former bookseller.