List price: $16.00

- Pages240

- ISBN9781612193618

- Publication dateApril, 2014

- Categories

- Booksellers

- Media

- Academics & Librarians

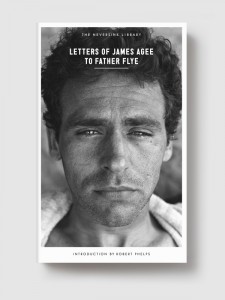

The Letters of James Agee to Father Flye

James Agee

Part of The Neversink Library

“Comparable in importance to Fitzgerald’s The Crack-up and Thomas Wolfe’s letters as a self portrait of the artist in the modern scene” – The New York Times Book Review

“I’ll croak before I write ads or sell bonds—or do anything except write.”

James Agee’s father died when he was just six years old, a loss immortalized in his Pulitzer Prize–winning novel, A Death in the Family. Three years later, Agee’s mother moved the mourning family from Knoxville, Tennessee, to the campus of St. Andrew’s, an Episcopal boarding school near Sewanee.

There, Agee met Father James Harold Flye, who would become his history teacher. Though Agee was just ten, the two struck up an unlikely and enduring friendship, traveling Europe by bicycle and exchanging letters for thirty years, from Agee’s admission to Exeter Academy to his death at forty-five. The intimate letters, collected by Father Flye after Agee’s death, form the most intimate portrait of Agee available, a starkly revealing account of the internal and external life of a tortured twentieth-century genius. Agee candidly shares his struggles with depression, professional failure, and a tumultuous personal life that included three wives and four children.

First published in 1962, Letters of James Agee to Father Flye followed the rediscovery of Agee’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men and the posthumous publication of A Death in the Family, which won the 1958 Pulitzer Prize and became a hit Broadway play and film. The collection sold prolifically throughout the 1960s and ’70s in mass-market editions as a new generation of readers discovered the deep talents of the writer Dwight Macdonald called “the most broadly gifted writer of our American generation.”

Praise for Letters of James Agee to Father Flye

“It would be hard to find a more honest account of the pressures of a writer’s life. Agee puts on no airs, writing intimately about his fears and doubts, even delving into thoughts on suicide. His portrait on the book’s cover—two pensive eyes gazing out from a face in need of a shave—seems a perfect representation of this brutal honesty. It’s as if Agee is daring the reader to pick up writing where he left off.” —Newsweek

“Comparable in importance to Fitzgerald’s The Crack-Up and Thomas Wolfe’s letters as a self portrait of the artist in the modern scene.– The New York Times Book Review

“A human document of searing honesty and naked beauty.” – Atlanta Constitution

“The stuff of life . . . Extraordinary letters which in their revelation of the hidden springs of genius constitute a major work of art.” – Pittsburgh Press

“Extraordinary letters . . . [James Agee] was what used to be called ‘an original’ . . . able to think in general terms without making a fool of himself, therein differing from most American creative writers of this century.” – Dwight Macdonald

“He simply preferred conversation to composition. The private game of translating life into language, or fitting words to things, did not sufficiently fascinate him. His eloquence naturally dispersed itself in spurts of interest and jets of opinion. In these letters, the extended, ‘serious’ projects he wishes he could get to . . . have about them the grandiose, gassy quality of talk.” – John Updike, The New Republic

“From a reading of the letters Agee emerges as a warm human being with a deep commitment to life as a person and as a writer. It is a rewarding experience to make his acquaintance.” – Kirkus Reviews

Praise for James Agee and Let Us Now Praise Famous Men

“A book of wonders—an untamable American classic in the same line as Leaves of Grass and Moby-Dick.” – David Denby, The New Yorker

“Let Us Now Praise Famous Men is . . . a classic work, an exercise in pure, declarative humanism. It will read

true forever.” – David Simon, creator of The Wire

“The most realistic and most important moral effort of our American generation.” – Lionel Trilling

“In my opinion, his column is the most remarkable event in American journalism . . . What he says is of such profound interest, expressed with such extraordinary wit and felicity, and so transcends its ostensible—to me, rather unimportant—subject, that his articles belong in that very select class—the music critiques of Berlioz and Shaw are the only other members I know—of newspaper work which has permanent literary value.” – W.H. Auden

“[James Agee’s] work continues to feel so vital just because it remains so nakedly vulnerable, so provisional, so utterly lacking in that subtle artistic poison of self-confident complacency . . . He honestly does seem something close to the James Dean of American literature.” – Michael Dirda, The Washington Post