July 31, 2013

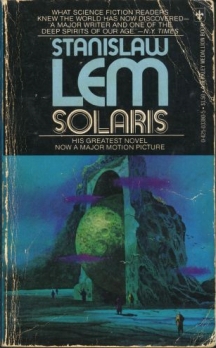

Failure to Communicate: on Stanislaw Lem’s Solaris

by Greg Cwik

Bibliophiles looking for something mind-probing and sort of social to do in Brooklyn this weekend may be in luck: there’s a marathon reading of Stanislaw Lem’s science fiction novel Solaris Saturday at the Wythe Hotel, presented by the Atlas Review, in collaboration with Marina Abramovic Institute.

Bibliophiles looking for something mind-probing and sort of social to do in Brooklyn this weekend may be in luck: there’s a marathon reading of Stanislaw Lem’s science fiction novel Solaris Saturday at the Wythe Hotel, presented by the Atlas Review, in collaboration with Marina Abramovic Institute.

The enigmatic Solaris, by no means a classic, ostensibly seems like an odd choice for a marathon reading: it isn’t as subversive and militarist as Robert Heinlein’s Starship Troopers and Orson Scott Card’s Ender’s Game, or as epic as Frank Herbert’s Dune, or as modern and edgy as William Gibson’s Neruomancer. It isn’t enveloped by a mythical aura, like the works of Philip K. Dick. It isn’t even very fun. It’s a paranoid slice of hard sci-fi, only 200 pages in length but vast in scope, concerned with communications and technology.

Human scientists are attempting to communicate with the sentient life of a far-distant planet, hoping to observe and study its inhabitants to—what else—better mankind. Surprise! Turns out the planet is the sentient life, and it’s observing and probing the scientists (in Soviet Russia, planet probes you!). Sated with fleeting human simulacra and surrounded by a viscous, varicolored ocean, the scientists’ research station becomes a microcosm of human fragility, and the scientists become lab rats.

For those keeping score at home, the novel has been translated from the original Polish and rendered in celluloid three times—in 1968, a black and white made-for-TV film that no one remembers; in ’72, Andrei Tarkovsky’s slow-burning mindfuck; and ’02, Steven Soderbergh’s unfairly maligned Americanization, which clocks in at half the length of Tarkovsky’s 3-hour monolith, and stars George Clooney’s luscious lips.

Tarkovsky’s film is widely heralded as the best adaptation of the novel by cinephiles (and Salman Rushdie), though, in typical Tarkovsky fashion, the auteur manipulates the source material to create his own piece of art, eschewing Lem’s theme of communication breakdown, which runs through the novel like an artery. Instead, Tarkovsky vivisects the innate faults of memory. Using his singular long, unsettling tracking shots through antiseptic white halls, pervaded by ethereal glimpses of spectral visions, he makes mental degradation visceral. The film feels at once stoic and saturated with melancholy; by the end, the viewer feels like s/he’s the one that’s been probed and studied.

The novel is a considerably more cerebral affair than any of the films suggests—more Arthur C. Clarke than Stanley Kubrick. Lem hated every adaptation of his novel, harboring particular abhorrence for Soderbergh’s romantic abridgement. He mused that his novel had nothing to do with “erotic problems of people in outer space.” His is a book of anthropomorphic limitations, of communication and miscommunication. “Solaris” is arguably a story that works best in written form, as the inherent malleability of prose lends itself to subjectivity, and subconscious alteration. Lem and the reader can never be simpatico, just like Solaris and the scientists.

What makes this marathon reading so fascinating is the promise of manipulation. The internal cogitation is being usurped— every one of the myriad readers will relay the novel in his or her own voice; the prose is always going to be filtered through someone else’s mind, reiterated in someone else’s voice. The reader is, in a way, being studied by the listeners, while the listeners are acting as individual observers, voyeurs: “It is not possible to think except with one’s brain, no one could stand outside himself in order to check the functioning of his inner processes.”