August 28, 2015

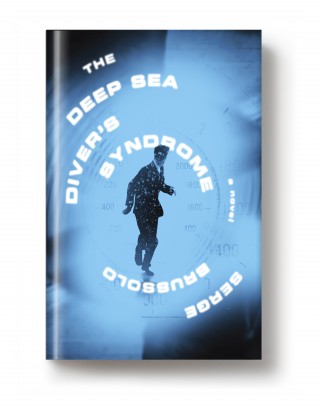

Fall Books Preview: The Deep Sea Diver’s Syndrome

by Taylor Sperry

We’re only weeks away from the launch of our Fall 2015 season, but why wait until September? Over the next couple of weeks, we’re giving you an exclusive look at the exciting new books about to land at Melville House—debut novels, major translations, and nonfiction about everything from dog walking to cocktail culture. We’ll feature a different excerpt every day, along with an introduction by our editors. Today’s book is The Deep Sea Diver’s Syndrome by Serge Brussolo, out January 19.

We’re only weeks away from the launch of our Fall 2015 season, but why wait until September? Over the next couple of weeks, we’re giving you an exclusive look at the exciting new books about to land at Melville House—debut novels, major translations, and nonfiction about everything from dog walking to cocktail culture. We’ll feature a different excerpt every day, along with an introduction by our editors. Today’s book is The Deep Sea Diver’s Syndrome by Serge Brussolo, out January 19.

Serge Brussolo might be the most famous writer you’ve never heard of. He’s as prolific as Stephen King, as brilliantly, disturbingly imaginative as Philip K. Dick and J. G. Ballard, and he’s an undisputed French master of the fantastic. And, yet, this is the first time he’s ever been published in English. In his novel The Deep Sea Diver’s Syndrome, professional dreamers take magnificent, physically exhausting dives into alternate states of consciousness, and they return to waking life with mysterious artifacts that become valuable pieces of art. The protagonist, David Sarella, is an expert dreamer whose glory days might be behind him, but who, despite many warnings, can’t help but push harder and harder against the limits of his own dives; the deeper he goes, the more difficult it is for him to return. As his adventures become more ambitious, it becomes unclear to David whether or not he’ll be able to return at all–and as readers, we’re not sure we want him to. It’s a novel that reads, from start to finish, like a dark, euphoric case of the bends.

—Taylor Sperry

I. Robbery in Deep Water

. . . the long, black, oily car clung to the sidewalk. Like a giant wet rubbery leech fastened to the foot of the building, siphoning blood from the façade, slowly gorging on the vital fluid flushing the pink marble . . . Would the structure shrivel up, wither away? Instinctively, David reached out for the car door to make sure the metal wasn’t going soft. He checked himself just in time. Rule number one: keep fleeting impressions from blossoming into full-blown fantasies. A moment’s inattention and images seized the chance to sink roots, proliferating at incredible speed—like tropical plants that, no sooner slashed, sprouted back, stalks dripping sap, amputees already reanimating . . .

. . . but still the long, black, oily car had something of the circling shark to it. Headlights like eyes unsettling in their steadiness, chrome bumpers like giant teeth that could mangle any prey. David felt the vehicle’s texture altering around him as the image gained materiality. Inside it stank of fish, the seat leather slowly growing scales. The air outside smelled of kelp, tidal scum foaming in the gutters . . .

“Stability issues,” Nadia muttered without looking at him. “You’re too nervous.” The fish reek was unbearable now. David leaned toward the door. The trunk and fender were halfway to becoming a huge caudal fin. The bodywork was beginning to bristle with sharp, tiny scales, a kind of wet leather that made his fingers prickle just looking at it. I’m being stupid. The young man forced himself to control his thoughts. This car looks nothing like a shark. Nothing. He had to pull himself together fast, because the view down the street was changing too, in keeping with the car’s mutations. The great white façade of the museum was looking more like a chalk cliff all the time, and the massive statues lining the front steps like . . . reefs. Timid waves were rising from the gutters to lick and lap at the first steps, dragging seaweed and driftwood in their wake. David blinked. The marble stairs were slowly eroding, the steps sagging, soft as sand. They melted into each other, forming a small, very white beach in the pale light of a full moon.

“Fix your stability,” Nadia said again. There was always a catch in that husky voice of hers. It was a tremendous effort for David to turn and look at the young woman. She’d hid her fiery red hair under a longshoreman’s cap and turned up the collar of her leather jacket to look more mannish, but her full lips with their ever-weary pout gave her away. “Quit fucking around,” she grumbled. “I’m about to turn into a mermaid here. I can’t feel my feet anymore.” She tried to laugh, but fear cut through the joke. She threw him a wild glance. “What’s with you tonight? This was supposed to be an easy job!”

David moved his tongue around, but could not manage to form a word. If the car turned into a shark, they’d both wind up trapped in its belly, in danger of being dissolved by stomach acid, right? It’s a car, he chanted, a mantra. Just a car. To convince himself, he began reciting tech specs from the handbook: top speed, miles per gallon city and highway—

The scales subsided; the trunk lost its finlike look. A car, a good old low-slung sports coupe that hugged the ground like greased lightning, quick as an attacking shark—no! Don’t start!

He turned his attention to the street, empty at this late hour. The museum statues stood guard along the sidewalk, sentries fossilized by fatigue. The tall façade of white marble unpleasantly intensified the streetlight glow. The jewelry boutique was on the other side of the square, a plush little setting for a window display with inch-thick glass proof against any explosive. David plunged his hand into the pocket of his leather jacket, came up with a big starchy handkerchief, and dried his sweaty palms. What time was it? He checked his diving watch. Its digital display blinked: Depth 3300 feet. Three thousand was enough to guarantee a good chance at success. He wasn’t going any deeper tonight, he could tell; he was too light. He hadn’t plunged into the water hard enough. His feet lacked that lead-soled shoe feeling that had heralded the vertiginous descents of his glory days. Still, three thousand feet wasn’t bad. Instinctively, he leaned toward the windshield to check out the sky, almost expecting to see columns of bubbles rising into the air.

“You taking off?” Nadia asked, worried. He nodded. The depth gauge showed 3295, which meant the ascent had begun; the longer he waited, the worse his working conditions would get. He had to act now. “Take a consistency pill,” Nadia suggested, handing him an unlabeled brass tube. David popped the top. A blue pill fell into the hollow of his palm. He swallowed it. “Remember,” Nadia whispered, “three’s the limit.”

He made no reply. He was well aware of the dosage. He took a great gulp of air, grabbed the metal briefcase on the back seat, and got out. He did not emerge from the jaws of a massive fish; the car had completely reverted to its original shape. As Nadia slid into the driver’s seat, he crossed the square, trying to come down hard on the cobblestones. But the clack of his heels lacked sharpness, revealing the material weakening of the world around him. It was a direct result of the ascent. As he drew closer to the surface, sounds would fade away, vases break in silence, the most devastating explosions morph into sneezes . . . He checked the depth gauge, worried: 3290 feet. A slow but irreversible ascent. He’d clearly observed the various symptoms right before his dive: restless legs, too-dry eyeballs that his eyelids painfully chafed, sweaty palms he tried to wipe on his sheets . . .

His metal heels struck the cobblestones with no greater sound than the distant echo of a tiny bell. He was tempted to punch the rounded belly of the briefcase to make it ring like a gong, but decided against it, less from fear of drawing attention than from dread of being met with only an alarmingly paltry noise.

He looked up again at the sky—at the surface. The moon’s silver disk stood out against the night. Once, not far from the moon, he’d glimpsed the hull of a ship at anchor . . . even fish. Fish, swimming among the chimney-tops overhead. He had to stop thinking about these things; all they did was hasten the ascent.

With a firm step he made for the boutique, whose window gave off a greenish glow in the dark. The pearls and tiaras behind the bastion of reinforced glass seemed half-buried in the silt. David blinked. No, not silt, cushions, just green velvet cushions. At any rate, the consistency pill would be kicking in any minute now. He had to seize that brief window and go to work. He approached the front door, which led to a kind of airlock where customers were detained for a moment before being allowed into the boutique. Once you had entered that cramped booth, a physiognomist went to work, scrutinizing you from head to toe through the glass, assessing your “financial standing” from tiny signs. If your shoes were nice, but alas, too new, that was condemnation enough; ditto for gems and diamonds of inadequate carat. Then a voice would come through the tinny speaker: “Sorry, sir, but perhaps you have the wrong address? There’s nothing in this store for you.” Humiliated, disgraced, you had no choice but to turn tail and shuffle from the vestibule like some indigestible scrap rejected by a healthy organism.

David dug around in his pocket, looking for the big key with the complicated blade for the first door. It hadn’t been too hard to come by, since getting past the first door wasn’t really getting into the boutique. Once you set foot in that airlock, that exam room—then, and only then, did things get serious. The key turned in the asterisk-shaped keyhole with a well-oiled click. A tiny light went on in the jamb of brushed steel. David put his hand on the glass and pushed. His fingerprints came off as little smiling faces, caricatures with a strong resemblance to his own features. It was as if each fingertip were a rubber stamp for certifying bureaucratic documents. He checked out his right hand. At the tip of his index finger he made out a faithfully engraved intaglio portrait of himself. He shrugged. None of this was important. Merely a rudimentary manifestation of guilt; he shouldn’t let this kind of thing slow him down—not even if, in a few minutes, his sweat went fluorescent like it had two months ago. He’d seen it all. During an earlier dive, his fingers had stubbornly persisted in leaving his name and address in black ink on every surface he must have touched. He entered the airlock; the door shut automatically behind him. The slightest mistake and he’d find himself a prisoner of the booth, which also served to trap burglars beating a retreat. It was a foolproof cell with an unpleasant foretaste of prison to it.

With the same key as before, David opened a panel set into the wall to his left, exposing a pane of frosted glass and an eyepiece that immediately lit up: two ultra-sensitive scanners, palm print and retinal. They’d been programmed for the shopowner’s right hand and left eye. The intrusion of any organs not matching the saved patterns would immediately set off every alarm in the store, and deadbolt the airlock doors on any stranger foolhardy enough to try the scanners. David set the metallic briefcase on the floor, popped the clasps, and lifted the lid. This was always a delicate moment—when he had to overcome his disgust. It was an effort to unfold the bloodstained napkin that held the jeweler’s severed hand. Nadia had done a clean job, with her expertise as a former army nurse. She’d amputated at the wrist without resorting to the bone saw she kept in her kit. “Better this way,” she often said. “He’ll have a nice clean stump, with no bone pain later.” David was quite certain that given the time, she would’ve gone so far as to stitch her victim up herself, from a sense of professional duty. He, for one, never watched the operations. He’d go into the next room, smoke a cigar, try to ignore the metallic sounds of the instruments. Nadia always put her patients under. She worked in white scrubs, as if presiding at an actual hospital. Her skill was astounding; she could’ve taught a real surgeon a trick or two. She worked without breaking a sweat, while the mere sound of a scalpel striking the edge of the stainless steel pan made David clammy all over with perspiration . . .

The square of frosted glass gave off a blinding white light, demanding that the first phase of the identification process begin immediately. If no hand was placed on its surface in thirty seconds, it would set off a general alarm. Finally overcoming his disgust, David grabbed the hunk of flesh by its sticky end and slapped the palm on the plate. It hit the glass with the wet smack of a bird flying into a window. The machine purred, gathering information. The retinal scanned blinked in turn, betraying its impatience. With his free hand, David uncorked the vial where Nadia had dropped the jeweler’s left eye, so carefully enucleated an hour ago. He swore. The gelatinous ball was slippery between his fingers. He didn’t dare squeeze, for fear of popping it. One false move, and he’d find himself imprisoned in the airlock, reduced to waiting helplessly for the police. Silently counting off the seconds, he finally got control of the eyeball and raised it gently to the level of the glowing lens. He knew he had to get it right side up; Nadia had made him practice the action at length, showing him how to tell if the organ was upside down from a few markers on the back. Fingers trembling, he held the ocular orb up to the black rubber eyepiece. The machine hummed again, and then the door to the boutique unlocked with a hiss of hydraulic pistons. David wrapped the body parts in the bloodstained handkerchief, stowed it in the briefcase, and entered the boutique.

The Deep Sea Diver’s Syndrome by Serge Brussolo; translated by Edward Gauvin

On Sale January 19

Taylor Sperry is an editor at Melville House.