February 12, 2015

The Art of the Novella challenge 14: The Duel (Casanova)

by Jonathan Gibbs

Author: Giacomo Casanova

First published: 1780

Page count: 70

First line: A man born in Venice to a poor family, with neither riches nor a title of any kind (which is what distinguishes families of note in the city from the ordinary people), but educated in a manner beyond his means, had the misfortune at the age of twenty-seven to incur the wrath of the city’s rulers.

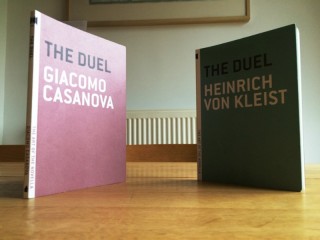

This is my second of Melville House’s five ‘Duel’ novellas, after Kleist’s 1810 account of a set-to between Sir Friedrich von Trotta and Count Jakob Rotbart over the honour of the Lady Littegarde. Here the duel is, again, over a woman – or rather because of a woman. The mechanics of how the story’s unnamed Venetian protagonist finds himself trading pistol shots with the Polish Count Branicki under a pergola in an estate outside Warsaw are easy to misread, and worth examining.

The Venetian (who I’ll stop shy of calling Casanova, even though the book’s fly-leaf informs us that the same story appears with minor alterations in the writer’s famous memoirs) is hanging out at the Polish court during an extended trip around Europe, when he upsets a ballerina, Anna Binetti – also a Venetian – by getting a bit too friendly with one of her rivals. She complains to Branicki, who promises to humiliate the cad. The two men soon cross paths at the theatre, where the Venetian has stopped by in all innocence to offer his regards to Binetti. Branicki confronts him, asks him in a not particularly friendly way if he (the Venetian) loves Binetti. When the Venetian says that he does (though it’s not clear what degree of love is in effect here – what they mean by it), Branicki says, in a manner clearly intended to escalate matters, that he will brook no rival.

“Very well, Monsieur,” responded the Venetian, in a somewhat humorous tone. “Faced with formidable gentleman like yourself, there is no man who would not obliged to back down. So I fully cede this lovable lady to yourself, with all the right that I might exercise over her.”

“I’m glad to hear that,” said the Podstoli [that’s another of Branicki’s titles] with an ugly expression. “But a coward who backs down, has backed down f..t le camp.”

It’s this taunt, rather than the whys and wherefores of who may be allowed to love or be loved by the ballerina (the right that he might exercise over her? really?), that sends the Venetian’s hand to his sword hilt. From there it’s but a small step, via some choice personal and national insults, to the exchange of psychotically polite letters requesting details of time and place where honours may be satisfied.

Whereas Kleist’s duel was for incredibly high stakes – the honesty and virtue of a high-born woman – and played out very much in the presence of God, this is a private arrangement brought about by the ignominious pile-up of i) a Venetian dancer’s wounded pride ii) a lovestruck Polish count’s sense of wanting to do what the Venetian dancer wants, and iii) a Venetian gentleman’s unwillingness to have his country’s name dragged through the mud.

Nor is the duel a duel to the death. The two men may talk about killing each other, but they’re more interested in trading a few blows for the sake of putting on a good show and then being done with it – and of avoiding the legal complications inherent in undertaking a banned practice. Branicki even turns up at the Venetian’s lodgings to go over the niceties of the arrangements.

“Let’s begin our duel with one good pistol shot apiece. Then, if you like, we’ll fight with swords until we’ve had our fill. This is the favour I am requesting. Can you really deny me such a trifle?”

On first read I found Casanova’s novella unpleasant and even boring. It seemed rather too interested in the social niceties of the duel, both before and after: whether it is polite to postpone the occasion because one has taken one’s medicine; who the doctor should attend to first in the event of mutual injury; the organisation of letters to addressed to all and sundry should this, that or the other happen.

In retrospect, however, I think I was coming at the book wrong, however. Having never read of word of Casanova, I was reading him through the lens of his popular image: that of a boastful and self-obsessed womaniser; and so I assumed that the story of the duel would, y’know, somehow involve the woman who instigated it, and that once his hero had dispatched the other man, there’d be some proper shagging.

As I read it, however, I found that the figure of the ballerina paled beside the account of the rivalry and then blossoming friendship between the two men. My original distaste, that it was the romantic dressing up of the age-old narrative of getting into a woman’s knickers, was supplanted by a second form of queasiness: that the duel was just an excuse for a ‘bromance’ between the Count and the Venetian, the heterosexual dressing up of the age-old narrative of two men strutting around in front of each other and bumping chests. They’re more interested in the exquisiteness of each other’s sensibilities, and the quality of each other’s pistols, than in any ballerina, beautiful of otherwise.

But this, too, is to misrepresent the book. Turning back to the opening pages, with its detailed account of where the Venetian travelled before he ended up in Warsaw, who he met, and how highly they thought of him, it’s clear that, just as Casanova is not primarily interested in the duel as a plot mechanism – a test for the hero to pass before he can get laid – so he is not using it as a metaphor for the very different press-and-release of male relationships.

The Polish count is as silly after the duel as before, with the two men mooning over each other in their shared ecstasy of post-battle, prestige-enhanced endorphins. The final pages of the novella returns to its original formula: a litany of the places, people, titles and honours the Venetian encounters on his journey from the Polish court.

Casanova is above all an observer, a cataloguer, a memoirist: he wants to put down how the world is, as he sees it. The duel is simply the event around which this particular set of social events orbit – and as such happens to extract itself from the totality of his experiences in the rough shape and length of a novella, a manageable chunk torn off the greater loaf.

He is interested in the constellation of facts: in each fact in itself (each detail, each grand person’s title, their heritage and personality), and in the relation it has to every other fact around it. The duel he relates may be nothing more than a simple, particularly compelling melody in the endless waltz of Life at Court, but like a constellation or a fractal it opens up when you zoom in on it to reveal a whole new (and entirely un-new, self-similar) set of notes, facts, relations.

That is what led to my misunderstanding. I had assumed that the novella was above all a metaphorical form, interested in showing the general nature of things through a singular, discrete instance. The further you dig into Casanova’s novella, however, the more surface you reveal. This is not meant negatively. I learned nothing about myself from reading this book (except about my prejudices as a reader), but I learned much about the world that Casanova moved in.

There is an anecdote dropped in at one point – in fact just when we’re building towards the crucial duel-instigating insult, when really things should be accelerating, narrative-wise – about the Queen of France, who used to eat in front of the entire court, and about how one should respond if she suggests to one in particular that “there is nothing better than a chicken fricassee”. Now, interesting as this anecdote is, it comes in entirely the wrong place, structurally, but then Casanova does not care. The connection he makes, or that occurs to him – and the relation it suggests – is what is important.

Jonathan Gibbs is the author of Randall, or The Painted Grape, published by Galley Beggar Press. He tweets as @Tiny_Camels and blogs at Tiny Camels