April 18, 2014

Hail & Farewell: Gabriel Garcia Marquez

by Wah-Ming Chang

There is a bookstore in Cartagena, Colombia, called Ábaco Libros y Café. Along a wall lined with wine near the entrance is a collage of black-and-white photographs of all the writers who’ve passed through. David Markson. Mario Vargas Llosa. Local Colombian favorites. Salman Rushdie too, added the owner, Maria Elsa Gutiérrez Pacheco, with whom I stared at the wall wondering where he was.

What about Gabriel García Márquez?

But this was a question I forgot to ask her.

García Márquez, who died yesterday in his home in Mexico City at the age of 87, lived in Cartagena for a year. A penniless student on arrival in April 1948, he spent the night first on a park bench and later, roused by the police for violating curfew hours, in jail. But not before they fed him a hot meal.

In Cartagena, he would write for the liberal newspaper El Universal under the pseudonym Septimus, and would fall asleep on the typesetting machine. He would write film reviews and screenplays, and help coordinate the Festival International Cine. He would find his literary voice, and fall in love with the lush Caribbean setting so much that the flavor of Cartagena would saturate many of his short stories and novels long after he left, most notably Of Love and Other Demons and Love in the Time of Cholera.

On an early April afternoon whose overcast sky gave way to a sudden golden sun, I sat down in Ábaco opposite a display of short novels by García Márquez and started reading Cholera for the first time. I had just given up looking for the office that rented out audio walking tours of García Márquez’s literary Cartagena, when I rounded one of those countless thin-sidewalked corners—this time a few blocks away from the famed fortress wall that separated the town from the water—and found Ábaco, a colorful oasis of books, coffee, wine, and geniality housed in an old warehouse space. The bookstore café started out twelve years ago solely as a bookstore; six years later, to attract more customers, Pacheco added the café.

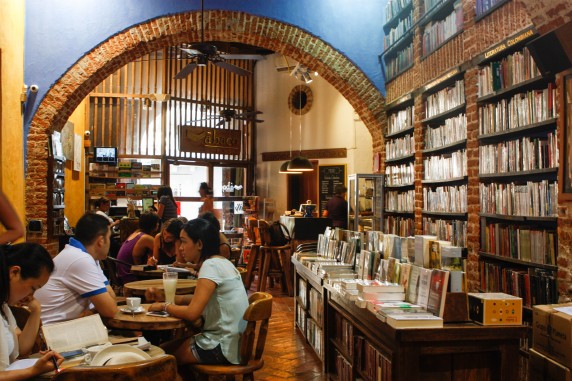

At the other end of the bookstore, framed by arches and walls packed in with old-school brick, hangs a projection screen. A ladder presses up against one of the walls. A long, thin display table (sporting a complete box set of the redesigned Kafkas, translated into Spanish) hugs the length of one wall, while small round tables fill out the rest of the space. When I sat down at one of these tables, I hadn’t known I would soon be reading García Márquez. Until then, I had read only the short story “A Very Old Man with Enormous Wings.” This reading does not count, however, because school had forced me to it, a long time ago, after which I never thought to explore further.

I stayed in Ábaco that afternoon reading Love in the Time of Cholera. I would spend the next day with the audio walking tour in my ears and my camera in my hands, and I would continue reading Cholera, often reaching the end of each sentence on the verge of tears. Experiencing literature away from home will always be a revelation. I am still reading the novel now, back in Brooklyn—during my commute to and from work, during lunch, before bed—but the flavor has changed slightly. The water is thinner here than it is in Cartagena, just as the sun is more muted, and the fruit tangier, and the ice cream too precious, and the pace at which I walk less aimless. Here, at home, I see how the characters in Cholera border on the sentimental. That’s all right, though, for García Márquez himself is not sentimental. What he is is the uncle who’s decided to tell you, for your own benefit, about the fate of a cast of doomed characters. And he does so, in his leisurely and roundabout fashion, by hyperbolizing the holy fuck out of these tragic, intertwined, predestined lives, out of history and love, of love and history. Call it magic realism, call it Nobel Prize-worthy, or call it false and self-exocitizing, as later generations of Latin American writers like Roberto Bolaño did, but there’s nothing you can do, really—or would rather do—but be held captive in the cage of his gilded words.

Ábaco’s display of Gabriel Garcia Márquez’s short stories and novellas. (All photographs by Wah-Ming Chang)

Inside Ábaco, and its regulars.

Inside Ábaco, and its tourists.

A detail of Ábaco’s wall of writers. Mario Vargas Llosa, who gave Gabo a shiner in 1976, is in there somewhere.

Book stalls in the Plaza de los Cochas.

Fermina Daza’s parrot, from “Love in the Time of Cholera.”

Gabo’s house, at Calle del Curato.

Wah-Ming Chang is the managing editor of Melville House.