December 10, 2010

Herman Melville and the new polytheism

by Melville House

Writing at The New York Times philosophy blog, The Stone, Harvard philosophy professor Sean D. Kelly has written an essay about how to navigate between the Scylla and Charybdis of religious delusion and self-deception and the anxiety and nihilism of Nietzschean post-God secularism.

Writing at The New York Times philosophy blog, The Stone, Harvard philosophy professor Sean D. Kelly has written an essay about how to navigate between the Scylla and Charybdis of religious delusion and self-deception and the anxiety and nihilism of Nietzschean post-God secularism.

Using such literary examples as T.S. Eliot, Samuel Beckett, David Foster Wallace‘s suicide and the suburban ennui in Jonathan Franzen‘s Freedom as examples, Kelly writes that “The threat of nihilism is the threat that freedom from the constraint of agreed upon norms opens up new possibilities in the culture only through its fundamentally destabilizing force.” (On the other hand, Kelly nicely points out the essentially religious thinking of writers like Times columnist David Brooks.)

Kelly turns to Herman Melville and Moby Dick to help re-imagine a life of value and meaning in a world devoid of the universal meaning provided by religion:

Writing 30 years before Nietzsche, in his great novel “Moby Dick,” the canonical American author encourages us to “lower the conceit of attainable felicity”; to find happiness and meaning, in other words, not in some universal religious account of the order of the universe that holds for everyone at all times, but rather in the local and small-scale commitments that animate a life well-lived. The meaning that one finds in a life dedicated to “the wife, the heart, the bed, the table, the saddle, the fire-side, the country,” these are genuine meanings. They are, in other words, completely sufficient to hold off the threat of nihilism, the threat that life will dissolve into a sequence of meaningless events. But they are nothing like the kind of universal meanings for which the monotheistic tradition of Christianity had hoped. Indeed, when taken up in the appropriate way, the commitments that animate the meanings in one person’s life ─ to family, say, or work, or country, or even local religious community ─ become completely consistent with the possibility that someone else with radically different commitments might nevertheless be living in a way that deserves one’s admiration…

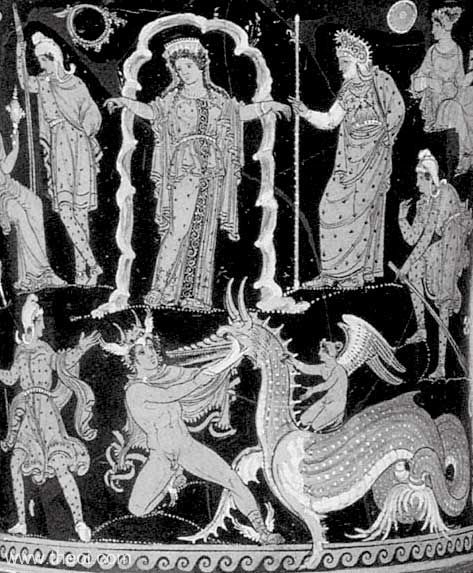

The new possibility that Melville hoped for, therefore, is a life that steers happily between two dangers: the monotheistic aspiration to universal validity, which leads to a culture of fanaticism and self-deceit, and the atheistic descent into nihilism, which leads to a culture of purposelessness and angst. To give a name to Melville’s new possibility — a name with an appropriately rich range of historical resonances — we could call it polytheism….

Melville himself seems to have recognized that the presence of many gods — many distinct and incommensurate good ways of life — was a possibility our own American culture could and should be aiming at. The death of God therefore, in Melville’s inspiring picture, leads not to a culture overtaken by meaninglessness but to a culture directed by a rich sense for many new possible and incommensurate meanings….

Indeed, Melville’s own novel could be the founding text for such a culture. Though the details of that story will have to wait for another day, I can at least leave you with Melville’s own cryptic, but inspirational comment on this possibility. “If hereafter any highly cultured, poetical nation,” he writes:

Shall lure back to their birthright, the merry May-day gods of old; and livingly enthrone them again in the now egotistical sky; on the now unhaunted hill; then be sure, exalted to Jove’s high seat, the great Sperm Whale shall lord it.

In his own blog, All Things Shining, Kelly points out the The Stone is “slated to end sometime before Christmas.” He writes:

If you believe, as I do, that it is a good thing for the paper of record to support first-rate philosophical discussions, please send an e-mail to that effect to [email protected], and include STONE in the subject line.

We encourage MobyLives readers to follow his advice.