March 18, 2014

How Harvard University Press made Walter Benjamin

by Kelly Burdick

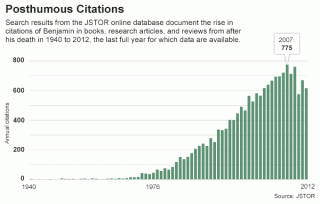

Benjamin’s citations in English

Following the suicide of critic Walter Benjamin in 1940, at 48, his name was “kept alive by a small number of friends and colleagues, the kind of trickle of a readership that hardly suggested he would one day be counted among the most significant and far-ranging critics, essayists, and thinkers of the past 100 years,” writes Eric Banks in the Chronicle Review.

Though Benjamin’s contemporary admirers included Hannah Arendt and Theodor Adorno, who helped Benjamin reach an increasingly large readership after 1968, it was the ambitious efforts of Harvard University Press and its executive editor, Lindsay Waters, that firmly established Benjamin in the English canon, as Banks chronicles in an appreciation of Waters and the press.

[H]is posthumous story can’t be recounted without consideration of Harvard’s positively European approach to bringing to print the critic’s writing, and sustaining it over time. Any writer should be so lucky to have such a long commitment—and it’s one that younger readers, who may find it impossible to recall how obscure Benjamin’s reputation was not so long ago, may not appreciate in its scope.

The case for Harvard’s role is made in a new biography of Benjamin, Walter Benjamin: A Critical Life by Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings:

The book is a victory lap for the press, which since publishing the first volume of Benjamin’s collected writings, in 1996, has turned out more than 3,000 pages of the author’s work, in addition to packaging essays in thematic volumes (like a 2008 collection on media, which included Benjamin’s vastly cited essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” or, as it’s more frequently translated, in the version written later, “The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility”).

Along the way, Waters was helped by an eclectic cast that included Daniel Bell, Paul de Man and T.J. Clark, who all understood Benjamin’s importance.

Of course, it’s a publisher’s job to act as a publicist, but Waters has always put his work on a different, higher plane. “This is what God put me on earth to do, to bring Benjamin to America,” he says, with a bit of mischief in his voice. And the divine mission is not done. Waters is quick to mention other books he still yearns to see in print: in particular, a volume of the radio speeches Benjamin wrote for children, work the author undertook in the late 1920s that, even if he liked to dismiss it as Brotarbeit, his bread-and-butter work, is a marvelous example of his interest in the mental world of children. A new translation of Benjamin’s correspondence is also on his wish list. But it’s hard to imagine that even these will fulfill Waters’s mission. After all, he says in passing, “Every sentence of Benjamin’s is worthwhile.”

Kelly Burdick is the executive editor of Melville House.