October 6, 2015

“I think it’s pretty clear you’re wrong”: An interview with Kirk Lynn

by Mark Krotov

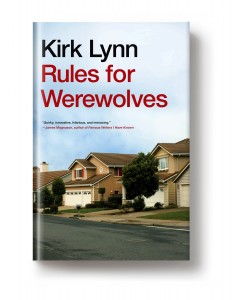

We’re publishing Kirk Lynn’s brilliant debut novel, Rules for Werewolves, in just one week, but we didn’t want to wait until publication to share this interview with the man itself. I asked Kirk a series of pretty conventional—even unanswerable—questions over e-mail, and the answers he gave me were so rich and unusual that I felt even worse about asking such prosaic questions. Interrogative quality aside, this interview is a perfect introduction to Rules for Werewolves. But if you find yourself in need of more of a fix before October 13th, we have you covered! Read an excerpt from the novel here, and take a look at Kirk’s commencement speech, delivered in May at the University of Texas. It’s a commencement speech unlike any you’ve read, which makes sense, because Kirk is incapable of writing anything that’s not totally unique and weird and beautiful. And be sure to read more about Rules for Werewolves here.

We’re publishing Kirk Lynn’s brilliant debut novel, Rules for Werewolves, in just one week, but we didn’t want to wait until publication to share this interview with the man itself. I asked Kirk a series of pretty conventional—even unanswerable—questions over e-mail, and the answers he gave me were so rich and unusual that I felt even worse about asking such prosaic questions. Interrogative quality aside, this interview is a perfect introduction to Rules for Werewolves. But if you find yourself in need of more of a fix before October 13th, we have you covered! Read an excerpt from the novel here, and take a look at Kirk’s commencement speech, delivered in May at the University of Texas. It’s a commencement speech unlike any you’ve read, which makes sense, because Kirk is incapable of writing anything that’s not totally unique and weird and beautiful. And be sure to read more about Rules for Werewolves here.

Where did this novel come from? Did the story precede the characters, or the other way around, or some third thing?

Ever since I was a kid, I liked to dream about running away, hiding somewhere and coming out at night when no one else was around and living off what I could scrounge. My eyes and my mind are drawn to the little doorway into the attic and the shed nobody uses and the weird little spaces in the back of people’s garages.

In high school we would break into for sale houses all the time for romantic/not-so-romantic date nights. You could pretend to be a couple and own the house, just without any furniture. And they were great places to hold little impromptu parties. We never did any real damage. We just wanted our own space in the neighborhood. We liberated the empty houses from their suburban slumber.

And I used to be a terrible drunk, so the idea of a violent transformation is something with which I have a little too much experience. I wish someone would’ve tied me up most nights I got into the tequila shots and beer. Every once in while I miss the deep wildness of being completely unhinged but I do not miss the aftermath.

Austin, where I live, has a long history of people sort of cheating and stealing and scamming the world just to get by. You saw Slacker, right? It’s a documentary as much as a fictional narrative. When I was an undergrad, most of my friends didn’t really work. They just got by. ‘Getting by’ was an art form in and of itself. Some of my friends are still making work in that genre.

So I think the story came from all those threads. The story came first and led me to the kind of characters who would be both bold enough and needy enough to try to live outside the system but in a group. And every group has rules and pressures to be both wild and self-possessed at the same time.

What inspired you to tackle a well-known form—the suburban novel—and turn it on its head?

In other writing I’ve talked about the idea that humans are animals and what we make is as natural as beehives or an anthills. The suburbs are simply the natural world I was born into. I love to read about people traveling out west in the olden days, but there’s no west left. I think it’s pretty well agreed the new frontier is largely interior. I think it’s in fact less exciting to think about where we are going to live and more exciting to think about how we are going to live. I think we’re just at the beginning of that exploration.

This morning my child’s battery operated dog that sings the abcs when you take it on a walk sneezed. I said bless you. No one else was in the room. I think the future has barely even begun.

At what point did you decide that this, unlike the vast majority of novels ever written, would be a novel told in dialogue?

As a playwright, especially for my theatre company, Rude Mechs, I write a lot of monologues. Dialogue accrues narrative much more quickly than monologue. And because our company is a collaborative ensemble, the text is more flexible if it comes in big monologic chunks that can be said by a cowboy or an heiress several months later once we decide who the characters are and where they are going to be standing.

I wrote fiction before I ever wrote a play. I read more fiction, too. It’s a form and a habitat in which I spend a lot of time. And narrative fiction, to me, welcomes dialogue.

I also like books that have a lot of white space. I just like the way they look and move. So all that led me to let the dialogue carry the narrative.

And as the characters interacted I think they also coalesced into a super-character—“the pack”—which has its own voice that wants to speak in full conversations, like those that take place at a great party with the perfect mix of beer and weed and liberal arts degrees and music and sneaking off to have sex and stealing food from the fridge. So some of the chapters are an attempt to give voice to “the pack” as a single entity that can only speak in dialogue and really only in unattributed dialogue.

This novel is extremely funny, extremely moving, and consistently riveting. Did you carefully parcel out bits of humor, emotion, and plot, like a chemist with a test tube, or were the elements inseparable from one another?

One of my favorite moments in my life was describing to my friend Annie Kaufman how no one ever knows if I am being serious or funny—and how, consequently, I get my feelings hurt a lot when people laugh at my serious ideas or don’t at my funny ones. But, I told her, I thought that was their problem. And she grabbed me and said, “No. That is your problem and you need to tell people when you are being serious.”

I haven’t necessarily followed her advice, but I don’t ever try to be funny or moving or even riveting. I think I try to be honest to my own desires. If I want a character to fall in love, I ask the character to express that. It usually comes out partly comic and partly sad. That may be more a feature of love than of my writing. Or it may be the nature of desire itself, which comes in the most complicated packaging.

You and I have somewhat differing interpretations of the novel’s titular werewolves. How much ambiguity did you intend?

I think it’s pretty clear you’re wrong. And I think when everyone reads the novel they will tell you that to your face. Then, if you admit you’re wrong, they’ll buy you a beer for being a good sport. But if you continue to argue and disagree, they’ll buy you a beer because they’ll feel sorry for you. You’re going to get a lot of beer either way, but don’t you want it to be for the right reasons?!

I think most of the characters are transformed by the end of the book. Literally. Strategically it didn’t seem like a good move on my part to get bogged down in the mechanics of what it physically looks like to transform in a dialogue-driven narrative (although I would argue there is some description of the transformation). But as my good friend and frequent collaborator Peter Stopschinski said when I asked him if I should have real werewolves in my book or just leave them as a metaphor: It’s more fun if they really change.

Also, I love you and like having feisty conversations with you about this, artisanal breweries, and growing cultural impact of MMA.

What’s next?

I’m working on a couple of new novels. Both revolve around lying. I was researching some famous prayers and came across George Washington’s prayer at Valley Forge, which is quoted in the biography by Parson Weems, also famous for the story of the cherry tree. As I looked into the book, it turned out that Parson Weems just happened to have a printing press and when Washington died, he thought, “man, if I had a Washington bio, I could make a mint!” And then decided to make one up based on the common knowledge of the man and filled it out with lies and embellishments. It seemed like such a rip-roaring way to write an American story. So I started writing my own lies about the General. It’s drafted but it’s psychotic.

I also became possessed of the idea of a religious sect based on nine commandments, keeping everything but the admonition against lying. As strange as it sounds, its actually coming out a little more melancholy and realistic. It revolves around a preacher who lives in a van and lives only with the help of a dizzying collection of prescriptions. When his van arrives in a vacant lot in a new neighborhood everyone sees him as a sad figure. But when he describes his own circumstances, living with the freedom not only to lie to others, but to define his own narrative, his story becomes regal and massively important to the fate of the world.

And there are always more plays, with the Rude Mechs and on my own. The Rudes are creating a piece for Yale Rep. called Field Guide, which will tell you how to live a good life, give you advice about giving advice, include some great stand up by Hannah Kenah, and possibly adapt The Brothers Karamazov into a short, little thirty-minute act of the performance. It’s early. I’ve got a new play currently entitled effective magic about a group of idiot, loser teens who make a haunted mansion into a clubhouse and use Stephen Covey’s 7 Habits of Highly Effective People to cast magic spells on bullies and parents, and most of all in the hopes of turning themselves into actual, useful, full-grown, powerful adults who aren’t poor and stupid and filled with self-hate and boredom.

Rules for Werewolves is out October 13.

Mark Krotov is senior editor at Melville House.