October 22, 2013

Iran announces a softening of book banning policies

by Dustin Kurtz

Jannati in 1981, back when he was Minister of Looking Like a Touring Saxophonist for Steely Dan

With the election of the relative moderate Hassan Rouhani, many in Iran have been anticipating some relief from the crueler restrictions of the Ahmadinejad presidency. And if, as the New York Times reported this week, street level changes have been slow in coming, the tenor of statements about censorship and banned books has proved reason for hope.

Speaking to IRNA, the nation’s official news agency, Rouhani’s new Culture Minister Ali Jannati announced “Those books subjected to censorship or denied permission to be published in the past will be reviewed again and new decisions will be made.”

But in a widely picked up statement to the semi-official ILNA Jannati goes further in deriding the overreach of the previous administration’s censors. In a translation from Radio Free Europe:

“If the Koran hadn’t been sent by God and we had handed it to book censors, they wouldn’t have issued permission to publish it and would have argued that some of the words in it are against public virtue,” he said.

Jannati said he had reviewed some of the titles that the administration of former Iranian President Mahmud Ahmadinejad censored and concluded that in many cases, censors had objected to “irrelevant” issues.

He also said in many instances censors had based their decisions on personal opinions, and added that the reviewers lacked the necessary expertise.

Jannati, perhaps significantly, is himself the son of a prominent conservative politician. And while he maintains the necessity of banning some books, his inclination to leniency in these matters would seem to be genuine.

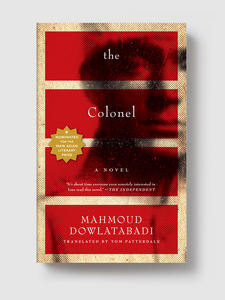

Even with a general thaw in the culture of censorship, I doubt the temperature will have warmed enough for an author such as Mahmoud Dowlatabadi, even beloved as he is, to publish his incendiary The Colonel there.The effects might be most felt by that nation’s many great publishing houses who would be able to publish a broader range of literature, domestic and international, and could avoid the variable delays caused by waiting for censors or, even worse, to have their books rubber stamped by censors only to be challenged and banned after printing.

An end result might mean more literature published overall, and thus greater potential for Iranian literary jewels to make their way abroad—surely a rewarding prospect for any regime, reformist or otherwise.

Dustin Kurtz is the marketing manager of Melville House, and a former bookseller.