June 23, 2015

James Joyce’s growing popularity in China

by Yifan Zhang

When people think about Bloomsday, the annual celebration of James Joyce’s Ulysses, they typically think of Dublin, the city in which the novel’s action take place—they probably wouldn’t think of Hong Kong. And yet, the region boasts one of Joyce’s most dedicated fan-bases. To mark this past Tuesday’s Bloomsday, Hong Kong hosted a day-long series of readings, accompanied by lectures and exhibits on the author—including one by a graphic novelist who adapted Ulysses into illustrated form.

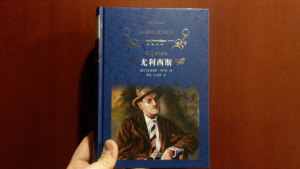

Joyce’s popularity in Hong Kong is less surprising when one considers China’s recent history with the author. Just last year, Shanghai People’s Publishing House ordered a 5,000 copy second print run of Dai Congrong’s Chinese translation of Finnegan’s Wake, which had sold out of its initial 8,000 print run within the first month of publication. There are also two Chinese translations of Ulysses, one of which saw publication in 1995 and both of which became bestsellers. More recently, the Guardian reports, “[t]wo Joyce-themed stage productions…recently toured major Chinese cities…and performed to full and enthusiastic houses in Beijing, Shanghai, Hangzhou and Jinan.”

Joyce’s popularity in China is all the more surprising when you consider Joyce’s prose, which does not lend itself easily to translation. Little of the puns, allusions, and visual/aural wordplay—each Joyce trademarks—are easily translatable to Chinese. And the greatest hurdle for the China-Joyce romance lies in his content—Joyce’s writing is spectacularly Irish, with a unique vernacular and intimacy which embodies the eccentricities of his native land. It is hard to crack even for a reader who is a native English speaker. For Chinese readers struggling through Ulysses, it is a Olympian task.

Yet, perhaps this is the very reason why readers in China and Hong Kong have flocked to Joyce’s works. Within Joyce’s prose is a history in conversation with itself, a history freely expressed and openly struggling with the good and the bad of its past and future. (Or, Stephen Dedalus, history as an unending nightmare.) Freeform and wild, his writing defies conventions and propriety—it still stands out for its audacity nearly 100 years after it was first published.

For many Chinese readers, alienated from their cultural history and suffering from enveloping media and self-censorship, Joyce’s writing can be something of a balm. In Joyce’s evocative depiction of early 20th century Dublin, Chinese readers experience the joys of having a rich and dynamic culture without fear of repercussion.

There is a term in Chinese for Joyce’s stream-of-consciousness style, “Yi Shi Liu.” In English it literally translates to “everything flows.” Right now the flow of thought and information is sharply curtailed for the Chinese people, but through Joyce they see the possibility of its existence. Here’s hoping it becomes more than a possibility soon. Maybe in a few Bloomsdays.