November 12, 2013

MobyLives reads Brad Stone’s The Everything Store

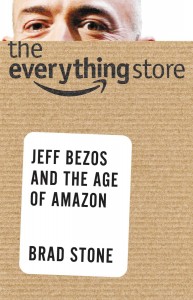

by Alex Shephard and Dustin Kurtz

Alex Shephard: Hi Dustin! Are you excited to order products from Amazon.com and have them delivered on Sundays, while you do your crossword puzzles and eat fluffy croissants?

Dustin Kurtz: Sundays are my day for squats, Alex. All kinds of squats. You should see my quads. You should feel them. And yes, I am excited. Moreso now that I’ve read The Everything Store by Brad Stone, and so can really appreciate the hard work, innovation, and, more than anything, the terrifuckingfying megalomania that went into getting me that box.

A: Yes. I bring up Amazon’s exciting new deal with USPS because it’s a perfect introduction to the way Stone approaches Amazon’s business model in The Everything Store. First and foremost, obviously, is its truly remarkable commitment to “customer service.” One theme of The Everything Store is that everything, from shipping to emails sent to lubricant-purchasers, at Amazon.com is done with Bezos’s mythoheroic customer in mind. But a second theme, very much connected to “the customer is always right” is that Bezos is willing to do anything to please this customer. He’ll wreak havoc. He’ll redraw the rule book. He is Grendel and Gilgamesh all in one and I don’t care that I’m mixing up my myths. Anyone who can’t keep up wasn’t meant to last anyway.

D: Right. I think in a moment we should address questions of whether this new biography of the relatively interview-shy Bezos is fair, but I want to talk about this idea that “he’ll redraw the rule book.” Assuming the biography is accurate—and I think we have to, Mackenzie’s objections aside—we get a detailed portrait of a man more obsessed with the myth of innovation than he is with minor details like human beings or even actual innovation.

Maybe it’s inevitable when the book’s interview subjects are all themselves consumers of the endless mythopoetic messaging this company spouts out, but more than anything you get the sense that the real concern of Bezos, and thus of the company, is exactly and only that messaging. They are a PR firm that ships toys.

A: They certainly do an admirable job at PR and they ship a shitload of toys, but I think they are actually innovative. Or, at least, they come across as such in The Everything Store (though, like most American innovators—shoutout Thomas Edison!—they stole as much as they invented). The story Stone tells is essentially the story of online commerce. Bezos successfully navigated that murky terrain and what he rightfully recognized—and what investors certainly have recognized—is that it’s a field with seemingly infinite growth. But while Bezos has certainly concocted a staggering amount of innovations in the field of online commerce, the biggest one is arguably the simplest: that online commerce has changed commerce itself, and is thus rewriting the rule book. Amazon rules online commerce, therefore they, like all victors, not only reap the spoils but write the rules. One example: Bezos seems to believe that in the online era any middleman that acts like a “gatekeeper”—one of the company’s favorite words—is dead. Every middleman except Amazon, that is.

D: Maybe my point here is more about the way business biography inevitably works but, think about it. Stone—who is critical at times but his admiration for (or fascination with) Uncle Jeff is clear—will often take pains to highlight those moments that have become legend in the culture of the company.

There are pages of people talking about Jeff’s ambitions, and about his doggedness in pleasing customers. But as far as real innovation, I don’t know if I see it. I see a man, a company, willing to talk about innovation but which was run, first to last, on old ideas. Half of his business goals are literally taken from Sam Walton’s book! Jeff was certainly a prescient investor, and I actually admire his obsession with getting himself into spaaaaaace (for his sake and ours), but, for instance, eliminating middle-men and exploiting your workforce with motivational pablum is nothing new. Maybe true moments of innovation are hard to portray. Particularly in a book reliant on a lot of stories that are essentially “so then we had a meeting and Jeff laughed a lot.”

A: And don’t forget: tons of pages about Jeff the child prodigy. I’m not sure if we’re meant to like or sympathize with this kid but child Jeff scared me. He came across like that weird kid from The Twilight Zone that turned people into jack-in-the-boxes.

D: Yeah, I mean, the real moral of the story is stay away from Jeff Bezos.

A: Yes! Or he will not let you into his space colony that will save us all from environmental apocalypse or whatever. Rich people are weird. And really into space! Space stinks. It’s scary and cold.

Stone’s relationship with Bezos is really fascinating to me, in large part because it—perhaps unsurprisingly—seems to drive the text itself, to provide the narrative arc. Stone starts fascinated by Bezos, by both his prodigious talent and his incredible drive. Frankly—and this might just be the sappy part of me that’s obsessed with sports—I found myself, like Stone, admiring young Bezos for these same reasons. But Stone apparently soured on Bezos around the same time the many of the rest of us did. That is, the mid-2000s.

D: My admiration flagged from about the tenth page when we find thirty-something Bezos trying to use math to pick up women and then dating and marrying his direct employee, but ANYHOO yes, Stone himself is fascinating. His history of journalism about Amazon shows a kind of obsession. Does he look up to Bezos? The book feels a bit like an exercise in parricide, doesn’t it?

A: Yeah, there’s a Hamlet-like element to it—Stone comes damn close to eviscerating the man on a few occasions, but ultimately holds back. I don’t think this necessarily hurts the book, but I do think Stone waffles because Bezos got in his head. Bezos doesn’t seem to read much fiction—though Remains of the Day, a very good book, is his favorite book—but he does read the shit out of pop business books, which shouldn’t come as much surprise. And he seems to be particularly fond of the sublimely, comically arrogant Nicholas Taleb and his book The Black Swan. Page 12 recounts Bezos lecturing Stone about “the narrative fallacy”—our tendency to oversimplify complex realities to make them more palatable—and Stone clearly struggles with how to present these complexities. He does an admirable job illuminating the murky and ever-changing world of online retail, but he definitely holds back on signposting, for better and for worse. There were a few times in the book where Stone seemed to hold off (in both praise and criticism) and I heard Bezos whispering “narrative fallacy” in his ear every time. (Ironically, Taleb’s description of “the narrative fallacy” is in itself a narrative fallacy as it oversimplifies what could be a very interesting concept into neoliberal garbage.)

D: Yes, that may be my favorite passage in the book—except all the talk about Digimon toys because, you know, that’s my jam—and I think it gets at my point above. Amazon has done such a good job of mythologizing itself from the very beginning that even with his 300-some interviews, Stone is surely left with little more than that myth to report. He gets a few details from dissenters, but everyone seems to be parroting Bezos himself. And, strikingly, Bezos is largely a voiceless character throughout. We hear him as he’s reported to us. Am I just fascinated by how biography works, Alex?

A: How popular biography works! You should read Richard Holmes. He rules. I heard he even bought some of the discounted Digimons Amazon sold to Mexico or whatever, because Richard Holmes loves two things: Romantic poetry and discounted Digimons.

One of the fascinating things to me about the Bezos in the book—and this only became more fascinating after MacKenzie one-starred the shit out of The Everything Store—is that you get no sense of Bezos the friend, or Bezos the family man, or Bezos the father. They are three Bezoses I would have liked to have known more about. I suppose that’s not terribly surprising, as Bezos didn’t cooperate with the book, so all Stone had to work from were interviews he did as a reporter, interviews that, unsurprisingly, find Bezos in full-on PR mode. (That said, Bezos RULES at PR mode. He should write a business book because it would be like 20 times better than Rich Dad, Poor Dad, which is, to my knowledge, the Ulysses of business books).

But another reason that interested me is that Amazon seems to be a very poor place to work if you have friends or a family. I have no idea, given the expectations and the schedule (or, if you work in one of their warehouses, the salary), how people there have families. That said, Bezos is apparently an exceptional time manager and I’m sure he excels everywhere. But a fuller picture of what its like to work at Amazon, whether you’re the founder or a manager or an engineer or, god forbid, a warehouse worker, would have rounded out the picture.

D: I loved the passages near the middle where Jeff is making everyone work through Christmas and just generally being a dick if people want to, you know, have lives, but then he takes a long paternity leave or is always on camping trips in California. Oh! Oh! Or the part where he starts flying in a private jet but “the company isn’t paying for it” so it’s okay, as if his personal wealth wasn’t built on the backs of everyone at the company. Even Stone, I think, may have a blind spot for this hypocrisy. As if Bezos’ obscene wealth is unrelated to the really brutal way he treated his workers, from the very first day of that company. I set out reading this book keeping track of every page on which Bezos shows himself to be a cruel boss but I stopped halfway through because eventually, if you are dog-earing every page, the book doesn’t close right anymore.

Yes, it seems that so much of our look into the warehouse experience came from interviews with people who did it in exceptional circumstances—very early on, or middle-management filling in for rushes. It gives it a cuter veneer than those conditions deserve.

And Alex, I’m not sure if that’s the correct plural of Digimon.

A: Is it Digimen? Mine always died. I am a bad Digiman and a worse Digiparent. Whatever.

I agree about Bezos’s hypocrisy, though I think Stone was occasionally aware of it—he seemed to take particular glee in recounting Bezos’s obsession with “the company isn’t paying for it.” But, like many of Bezos’s flaws—we learn of Jeff’s anger problems, for instance, but are reassured that he now has a life coach—they seem to be quickly muddied to create a more human Jeff. That’s all well and good but it seems like we both agree that the portrait that emerges isn’t fully human—it’s complicated, but doesn’t feel quite complete. That goes for Amazon as well, though I think that Stone accomplishes a great deal. I have a better sense of Amazon, as complicated, contradictory, and mercurial as it is than I did when I read the book last month.

D: Yes, I agree. The book is worth reading, particularly if you want to witness a journalist searching for his thirteen-thousandth metaphor for the peculiar noise of one man’s aggressive laugh. But it is not the last word on this company or this man. And I maintain that we may never see a book that doesn’t feel as if it’s recounting legend, precisely because self-referential legend is more or less the business that Amazon is in.

A: Yeah, let’s talk about the elephant in the room: the gatekeeper’s gatekeeper, the shitty businessman’s business… the publishing industry! The publishing industry does not come off so well in this book, Dustin, though that’s not terribly surprising. Stone goes to great lengths, as we’ve discussed, to portray Amazon as a complicated company. It’s clear that he sees their assault on the American commercial landscape as an inevitability and doesn’t feel a great deal of sympathy for those who were unable to recognize the changing terrain.

The publishing industry, particularly in the midsection of the book, comes across as remarkably arrogant and hubristic—there’s even an air of Greek tragedy about the tragic, out of touch New York socialites running these dinosaur companies. They don’t realize what’s happened until it’s too late and appear to be astonishingly slow to adapt. And they pay dearly for it—the $9.99 surprise in particular—and, instead of attempting to adapt, they enter into what looks to be one of the more poorly executed conspiracies in American business history. Always let your lawyers in the room, folks.

Still, no one comes across as badly as poor old Len Riggio, who badly miscalculated. “When the market is there, we’ll be there,” which Riggio said about the ebook market, now comes across as last words-worthy, though Barnes & Noble seems to be regaining a bit of its fighting spirit.

D: Yes, publishing is, in this book, stodgy and hilarious—deserving of their comeuppance. Of course I’m always willing to believe that I deserve to be punished for something I may not remember doing, so all of that was very satisfying.

Len Riggio is a fascinating character in the book; Bezos is Stone’s everyman, his reader stand-in, and so with every other executive we’re treated to descriptions of their rings and cars. At first Riggio is portrayed as a greedy Disney villain of the bumbling variety, but by the end you pity the guy.

The thing about ‘disruption’ is that you really can’t guard against it. That’s exactly the point of one of those terrible pop business books Bezos makes his team read. An adult (not that kind of adult, Alex) industry is very much just a head-down ‘do what we do and try to do it well’ affair. They are in a different business than ‘disruptors’ like Amazon. Amazon—by design—has yet to really be a stable presence in in any coherent ‘industry’ so they haven’t had to contend with that kind of stasis. That’s to their credit but not, I’d say, to the discredit of publishers.

A: That’s a great point, and one that I think is central to the book’s successes (and its failures). In The Everything Store we get a fairly compelling picture of a disruptor, but we don’t get a similar portrait of the disrupted—the “narrative fallacy” doesn’t seem to apply to them. And, in Amazon’s case, this new “disrupted” group isn’t just made up of Duck Tales villains like Riggio. It’s made up of the employees of stores like Borders and Circuit City, of small business owners and, crucially, of people who try to make their living as third-party sellers on Amazon and Amazon employees themselves. I kept clamoring for that book—a book that takes on the disrupted as well as the Chief Disruptor Jeff Bezos—which has yet to be written. I’m sure someday it will. But by then there will only be one company and it will deliver everything every day of the week on the same day that you order it and it will be called diapers.com.

D: Yeah, that’s the book I’d like to read. A counter-mythology. And I will. So long as an Amazon-branded postal carrier drops it into my sweaty sweaty squat-lap.

Alex Shephard and Dustin Kurtz work at Melville House and are friends.