February 14, 2014

Modern-day samizdat: publishing LGBT voices in Russia

by Christopher King

As the 2014 Winter Olympics head into their second week, all eyes are on the sporting events and political controversies unfolding now in Sochi. Attracting less attention is Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev’s quiet signing this week of a new anti-gay law which prevents the adoption of Russian children by same-sex couples or by single parents who live in any country which recognizes same-sex marriage, according to The Telegraph:

As the 2014 Winter Olympics head into their second week, all eyes are on the sporting events and political controversies unfolding now in Sochi. Attracting less attention is Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev’s quiet signing this week of a new anti-gay law which prevents the adoption of Russian children by same-sex couples or by single parents who live in any country which recognizes same-sex marriage, according to The Telegraph:

The decree, which is dated February 10 but was posted on the Russian government’s website on Thursday, is officially intended to “help improve the procedure for transferring children without parental care to families of Russian and foreign citizens, and to protect the rights and interests of these children.”

The amendments to the Russian adoption law that were signed by Mr Medvedev include a bar on adoptions by “those in a same-sex union recognized as a marriage and registered in accordance with the law of states in which such marriage is allowed, and also citizens of such states who are not married.”

More infamous, of course, is Russia’s 2013 law against “homosexual propaganda,” effectively banning all forms of speech in support of gay rights. Western media have extensively covered the law’s most obvious consequences—public demonstrations thwarted, activists arrested, LGBT people beaten and tortured—but equally important is the stultifying effect of the law on Russian culture, including literature. In fact, it has forced the reintroduction of a literary form presumed to have ended with the USSR: samizdat, the illegally self-published texts circulated surreptitiously by Soviet dissidents.

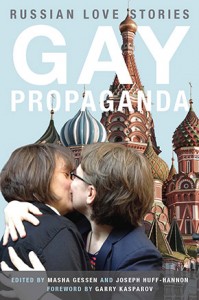

As with writers like Alexander Solzhenitsyn and Mikhail Bulgakov in the Soviet Union, LGBT writers in modern Russia have suddenly found themselves silenced, unable to write honestly or speak freely about their lives without breaking the law. Now some of these voices have been collected in a new book of stories and testimonials called Gay Propaganda: Russian Love Stories.

Although the book cannot legally be distributed in Russia, its publisher, OR Books, hopes Russian readers will pass around electronic copies in the same way samizdat texts were passed hand-to-hand in the twentieth century. Joseph Huff-Hannon, one of the compilation’s editors, spoke about this effort in an interview with The Rumpus:

Joseph Huff-Hannon: Masha [Gessen, the book’s co-editor] describes it as being a part of this legacy that comes out of literature that was banned in the Soviet Union. People took it upon themselves to print DIY books, so books would be either written by dissidents within the Soviet Union or without. They were basically books that weren’t supposed to exist. They were circulated friend-to-friend, colleague-to-colleague. This was a way to tie together a community of dissidents.

In terms of modern-day Russia, there’s a category of cultural expression that has been banned, and that category contains everything that has to do with LGBT people that’s not disparaging. For instance, you can make a TV show or write a book that paints gays and lesbians as evil. That’s actually legal because there are statutes under the law that describe how you can talk about LGBT people.

There’s a limit to how this book will reach Russians. Bookstores are not going to pick it up. We’ve already heard from journalists and journals who are saying, “This is interesting, but we can’t write a review or cover it because we might end up in court.” The way we suspect this book will get circulated is through word of mouth, through friends, through networks of liberals, human rights groups, and LGBT people and their friends and family.

Rumpus: Are you planning to send copies over there?

Huff-Hannon: That’s the plan. The first stage, right when the book publishes, is that it has the free e-book for any reader and the free PDF of the Russian manuscript. We’re going to get that circulating on blogs and social media, and there’s a longer plan to get print books and get them into Russia. A big part of the population in Russia is basically getting disappeared by the media right now.

Huff-Hannon also discusses how the Internet has both helped and hurt LGBT people in Russia:

I can give you very blatant examples. People might come to a moment in their life when they’re like, “Fuck it.” And they say something online, and they let it out of the bag, and now they’re in the U.S. because they went through [coming out], and it wasn’t long before they lost a job or they were attacked or faced other kinds of ostracism. But they also use the web as a forum to say, “You know what? Now I’m going to post pictures of my wedding on Facebook.” There’s something powerful about the web as a space for assessing the temperature for where there’s a consensus.

Read the full interview at The Rumpus. Gay Propaganda: Russian Love Stories is available now from OR Books.

Christopher King is the Art Director of Melville House.