January 23, 2015

New details emerge in the story of the boy who did not come back from heaven (because he never went there in the first place)

by Taylor Sperry

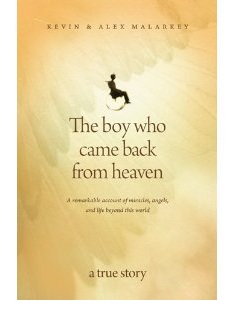

Last week, Alex Malarkey, the co-author of the bestselling memoir The Boy Who Came Back from Heaven, posted an open letter on The Pulpit and Pen saying that the details of his book–details drawn from a two-month coma he suffered at the age of six–are false. “I did not die. I did not go to heaven,” he writes. “I said I went to heaven because I thought it would get me attention.”

Last week, Alex Malarkey, the co-author of the bestselling memoir The Boy Who Came Back from Heaven, posted an open letter on The Pulpit and Pen saying that the details of his book–details drawn from a two-month coma he suffered at the age of six–are false. “I did not die. I did not go to heaven,” he writes. “I said I went to heaven because I thought it would get me attention.”

Whether or not this struck you as a surprising turn of events, what is surprising (or should be) is what we’ve since learned about the relationship between the Malarkey family and the book’s publisher, Tyndale House. While the publisher maintains that this was all news to them (they were “saddened to hear that Alex is now saying that he made up the story of dying and going to heaven”; they took the book out of print “immediately”) Michelle Dean‘s article for The Guardian on Wednesday suggests that Alex and his mother, Beth Malarkey, had been trying to set the record straight—both with their publisher and with the public—for years.

Starting in 2011, the Malarkeys addressed the book’s inaccuracies on its Facebook fan page, on personal blogs, in online forums, and in the email exchanges with Tyndale that have since been obtained by The Guardian. Meanwhile, Dean writes, “Tyndale House kept publishing a book with a quadriplegic boy’s name on the cover, even though it knew he had substantial objections to the book.”

To focus on the book’s “inaccuracies” is, of course, to miss the point. This was always going to be a story that traded in faith. But what feels problematic is the evidence that a publisher would exploit an author–in this case an author who had a book deal before he’d even turned ten–in the service of capitalizing on a trend. Times are tough, and “heaven tourism” books work (Colton Burpo’s Heaven Is for Real has sold more than eight million copies since it was published in 2010), but it seems like we should be able to do a little better than this.

Taylor Sperry is an editor at Melville House.