June 12, 2013

North Korea: your source for bombastic monuments

by Sal Robinson

In its nearly seventy years of existence, North Korea has honed its skills in at least one area: socialist realist propaganda art. And they’re so good at it these days that they’re selling it to the rest of the world.

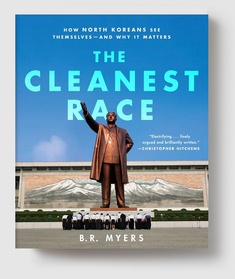

A recent article by Caroline Winter in Bloomberg Businessweek profiles the Mansudae Art Studio, a massive factory in Pyongyang that turns out propaganda art by the barreload, from the tiniest “Kim pin” to gigantic stone sculptures of noble workers, brave soldiers, and no doubt the occasional heroic little mother. They make these particular products for the domestic market (including the famous Mansudae Grand Monument, depicting Kim Il-sung and Kim Jong-il, and pictured on the cover of B. R. Myers’s The Cleanest Race), but they also have a very successful export side, knocking up monuments to order for foreign markets.

The Bloomberg article follows the re-creation of Frankfurt’s “Fairy Tale Fountain,” an art nouveau creation that was melted down during World War I for the bronze; Mansudae’s employees reconstructed it based on old photographs. Klaus Kemp, deputy director at Frankfurt’s Museum of Applied Art, explained the decision to choose Mansudae for the job:

It was a purely technical decision. The top tier artists in Germany simply don’t make realist work anymore. North Koreans, on the other hand, haven’t experienced the long evolution of modern art; they are kind of stuck in the early 1900s, which is exactly when this fountain was made.

In recent years, some of Mansudae’s biggest customers have been in Africa: they’ve had four major commissions in Namibia alone since 2000, including the new Namibian State House, with “life-size statues of native animals.” Other Mansudae sculptures dominate plazas in Botswana, Zimbabwe, and Senegal. Here’s Dakar’s African Renaissance Monument, which stirred controversy in the predominantly Muslim country because of its scantily clad female figure:

Like Ian Johnson’s recent New Yorker piece on Hengdian World Studios, the Chinese movie lot that is now the world’s largest and probably the only place on earth where you can see the “Anti-Japanese War” (one of the terms used in China for the Second World War) fought over and over again on a daily basis, the vast scale of art-making that Winter describes has its own fascination.

One of the most memorable moments in the recent film “The Autobiography of Nicolae Ceausescu” (which is composed entirely from archival footage) is a scene from 1971 in which the Ceausescus visit North Korea and are greeted with spectacular choreographed mass art—hundreds of North Koreans functioning like pixels, composing stadium-scale images depicting the history of the Romanian Communist Party—and the expression on Ceausescu’s face is one of pleasure, envy, and awe. You can almost hear him thinking, “These people know how to do this right.” It’s a deeply disturbing moment, both because it presages the expansion of Ceausescu’s own personality cult, once he returned home to Romania, and suggests that dictators plagiarize from each other as much as any other competitive group of individuals.But if you want your own piece off the Mansudae production line and you’re not an international dictator, there’s still a way: Winters reports that the artists of Mansudae, highly proficient in both realist painting techniques and in copying stuff, are probably responsible for the Canaletto and Vermeer knockoffs for sale on the streets of many European cities.

“If you’re standing on the Seine and you buy a painting from one of those stands, there’s a good chance it was made in North Korea,” says Klemp. “I can’t imagine that those artworks are sold locally.”

Sal Robinson is an editor at Melville House. She's also the co-founder of the Bridge Series, a reading series focused on translation.