September 26, 2013

Contemporary Iranian literature flourishes despite government censorship

by Michael Elmets

Image via Shutterstock.

While Iran has historically been home to one of the world’s richest and most vibrant literary cultures, in recent years, civil unrest, political pressure, and government censorship have transformed the country’s literary scene. Government censorship of literature has been a problem in Iran since at least the late 1990s, 2009’s Green Revolution, during which tens of thousands of Iranian citizens took to the streets of Tehran in protest of the disputed election victory of controversial former President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, led to an intensification of political repression of writers. And, in the years since the massive demonstration, not even 86-year old poet Simin Behbahani, who is referred to as the “Lioness of Iran” and who has twice been nominated for the Nobel Prize in literature, has been free from political intimidation.

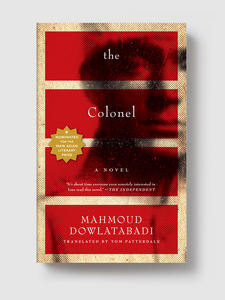

Despite such widespread repression and censorship, Iranian writers have refused to be intimidated and have found alternate means of getting their work to the public. For some of the most prominent Iranian writers, the need to avoid censorship has meant publishing in places like Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States, where Melville House has published translations of Mahmoud Dowlatabadi’s novels Missing Soluch and The Colonel. (The Colonel is still unpublished in Iran.) Other prominent writers like Abbas Maroufi and Amir Hassan Cheheltan have been obliged to leave Iran altogether for extended periods, but have used the distance afforded by life outside of Iran to produce some of the most interesting and moving literature written about contemporary Iran.Still, according to a friend who lives in Iran, the most interesting development in contemporary Iranian literature has been the rise of poetry reading nights. While many of the writers most closely associated with these poetry readings are as yet unpublished in Iran or other countries, video footage of readings by some of the most political of the performers like satirist Mohammad Reza Ali Payam (also known Haloo, or “the idiot”) and Hila Sedighi is available on YouTube. Though “Haloo” and Sedighi have each been threatened, arrested, and sentenced to prison terms, they have stayed in Iran and have continued to produce poetry inspired by the political situation in the country.

While political censorship has undoubtedly taken its toll on Iranian literature, the ability of Iranian writers both young and old to adapt and to go underground, overseas, and on the Internet in order to distribute their work has helped to preserve some of the vibrancy of Iran’s literary culture. With the potential for an easing of tensions between the United States and Iran, it will be interesting to see if more of these exciting authors will be able to find an audience in the United States.

Michael Elmets is a Melville House intern.