February 5, 2013

On the anniversary of Hans Fallada’s death

by Kevin Murphy

“Writing is the essence of my life.” –Hans Fallada

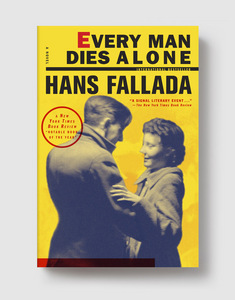

One of the twentieth century’s greatest writers, Hans Fallada, died of heart failure on this day in 1947. Fallada struggled with substance abuse, and after suffering a heart attack during the early winter of that year, was confined to a sanatorium where he spent his days with family and waiting for the publication of Every Man Dies Alone, his masterwork about a German couple who defy the sanctions and intimidation of the Nazis by circulating postcards of dissent in various areas of Berlin during World War II.

Every Man is as much a story about love as resistance; a testament to a middle age married couple’s determination and character and the courage to pursue integrity and freedom despite facing risks of unfathomable terror. Fallada wrote the novel in what he described as a twenty-four day period of “white heat.” Sadly, he would not live to see its publication — he died weeks before the book’s release.

Melville House is proud to say we’ve published Fallada’s most important books, including Little Man, What Now?, Wolf Among Wolves, The Drinker; and Every Man Dies Alone.

Of this last book, Alan Furst proclaimed: “Hans Fallada’s Every Man Dies Alone is one of the most extraordinary and compelling novels ever written about World War II. Ever. Please do not miss this.” The great Primo Levi called it, “The greatest book ever written about German resistance to the Nazis.”

We’ve recently re-released our four Fallada titles as HybridBooks, meaning they’re now accompanied by Melville House “Illuminations.” In these pages, ancillary material — interviews, never-before-seen photographs, rare essays by the author — is paired with the original texts, offering the reader new and important insights on Fallada the man, father, and author black-listed by the Nazis.

In March 2012, Melville House co-publisher Dennis Johnson travelled to Germany to meet Fallada’s son, Dr. Ulrich Ditzen, who at 82 retained vivid memories of his father’s final days. The following is a brief excerpt of an interview Johnson conducted with Dr. Ditzen that appears in the Illuminations for Every Man Dies Alone:

DJ: When was the last time you saw your father?

UD: On his deathbed.

DJ: Did he know he was dying?

UD: I think he did not but I cannot substantiate it.

DJ: What was that last meeting like?

UD: I brought cigarettes to him. He was in a sanatorium for ladies of the street. So he considered it very funny that the great German writer was combined with such ladies. [laughing]

DJ: That was where he was?

UD: [laughing] That was where he was. The house is still standing.

DJ: And so he had you bring cigarettes to him?

UD: He needed them very much. He was a real cigarette addict. Even though he had just had a heart attack.

DJ: Was it a good meeting? Was he in good spirits?

UD: Mostly he was. I went to see him regularly until the end.

DJ: So, what do you think he would make out of his renewed fame today? Would it surprise him, do you think?

UD: Not really. [DJ laughs] No, not really. He knew he was a good man.

DJ: He was confident?

UD: Yah.

DJ: Confident of his writing?

UD: That’s right.

DJ: That gladdens me to hear that.

Discouraged by the debilitating effects of his morphine addiction, Fallada worried that he was a failure, and that his life lay wasted. Despite being remembered by his son as confident until the very end, Fallada expressed remorse and frustration in a letter written to his mother shortly before his death.

In this brief excerpt from the Illuminations, Fallada scholar Geoff Wilkes discusses the letter Fallada wrote to his mother from his deathbed:

On December 22, 1946, Fallada wrote to his mother from a hospital in Berlin, describing his memories of his father, of his aunt Adelaide (who had helped him at various stages of his literary career), and of his brother Ulrich (who had been killed on the western front in August 1918):

“It’s good that they’re all dead, anyone who doesn’t have to endure this life here now can count themselves lucky. You probably already know that we’re both sick again, [his second wife] Ulla and I, first exhaustion, then abuse of sleeping drugs, then — always the same old story! I’ve already recovered a little, even though I can’t do anything like proper work yet [. . .]

I’m really only living for the children now, and I’m glad that they’re both such good and such promising children, and I wish so much that their lives will be rather easier than their father’s. Where did I go wrong, Mom? I always work hard, and long, and carefully, and I really love my family, but then I myself often destroy in a few hours what it took me months and years to create. Now I’ve written a truly great novel again, in a very short time, a novel that will be a success, I already had the fruits of my labors in my hand, and now I’m sitting here abandoned and alone, after wasting everything I had achieved again. Something in me never quite developed properly, something is lacking in me, so that I’m not a proper grown-up man, only someone who has grown old, a high-school student who has grown old, as [fellow author] Erich Kästner once described me. I tell myself today that these breakdowns have to stop, that I must live more sensibly, but I don’t want to make promises to myself anymore — let alone to other people—because I have broken such solemn promises so many times. So I’ll only say that I want to try again, I want to work, and work hard—let’s hope than I’m spared to do so for a long time! […]

Of course you know better than anyone that I may be a weak man, but not a bad one, never a bad one. That’s no excuse, and it’s bad enough that at fifty-three I haven’t become anything more than a weak man, that I’ve learned so little from my mistakes. But that’s undeniably how it is.”

Fallada was indeed a well-regarded, popular author before his death. However, despite some acclaim in America and the UK, he and his work slipped into obscurity outside of Germany during the post-WWII years.

Led by his rediscovery by Melville House, however, his work has become a world-wide phenomenon, with his books in translation and on bestseller lists around the world, and many of literature’s brightest lights commending his work. Fallada’s legacy remains vital, influential, and, on this, the anniversary of his death, full of life.

Kevin Murphy is the digital media marketing manager of Melville House.