September 19, 2012

Oulipo, OuMuPo, OuPeinPo, OuBaPo, etc.

by Sal Robinson

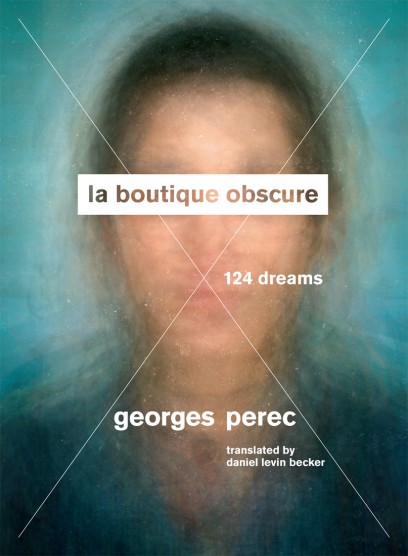

In fall, one’s thoughts turn to the battening-down-of-hatches, the finiteness of time, and in due course, constraints, and then, naturally, but also possibly as an escape from the lowering gloom, to the Oulipo movement. Whose youngest member Daniel Levin Becker is the translator of the forthcoming, never-before-translated La Boutique Obscure: 124 Dreams, Georges Perec’s extraordinary dream journal from the late 60s. (There will be dentists.) It has hypnotizing and beautiful cover, and something may or may not emerge if you move your head very quickly towards and away from the computer screen while focusing on the middle of it.

Levin Becker is the author of a recent book on the Oulipo, Many Subtle Channels, which was recently the subject of a three-part series by Matt Rowe on Three Percent (part 1 here, part 2 here, part 3 here), which describes Levin Becker’s introduction to the Oulipians:

The first third of Many Subtle Channels recounts his experience of discovering, meeting, and finally joining this strange group. Levin Becker first encountered the Oulipo as a Yale student, when George Perec’s story “The Winter Journey” was assigned in his French class. After college, he was awarded a Fulbright fellowship to go to France with a (he admits) ill-defined project to study the Oulipo. He soon found himself put to work as the group’s “slave,” organizing its archives; only after he had left France did he learn that he had been elected to membership himself. He invites us to “think of the Oulipo … as a search party for those of us who don’t know what we’re looking for.”

Rowe also draws attention to some little-known (at least to me) corners or associates or affiliates of Oulipo: OuMuPo, OuPeinPo, OuBaPo, OuTyPo, and OuWiPo, for music, painting, comics, typography and Wikipedia respectively; the Italian counterpart, OuLePo; past and present writers who wrote work we might consider Oulipian, but who aren’t actually members, like Jorge Luis Borges, Stanisław Lem, Milorad Pavić and, more recently, David Mitchell and César Aira.

The real significance of the Oulipo, Rowe argues, may be in the stance towards reading that their work invites:

The key lies in reading, not writing. As Levin Becker points out, those members who studied the Oulipo before becoming members learned to read “oulipianly” before they learned to write that way … this has much more to do with Barthes’ notion of “readerly writing.” As explicated by Tom La Farge, readerly writing engages the reader as a creative collaborator. For the writer, “the process of composition is … an experience of reading,” and the reader in turn becomes “an active participant in the composition process.” The oulipian reader, like the oulipian writer, is always re-reading, re-creating, re-membering. Levin Becker claims this “creative reading” — in effect, writing in reverse — “is no less noble, no less rewarding, no less potentially spectacular, than creative writing.”

Sal Robinson is an editor at Melville House. She's also the co-founder of the Bridge Series, a reading series focused on translation.