October 4, 2013

Ten highlights from David Bowie’s reading list (set to David Bowie’s music)

by Amy Conchie

David Bowie’s 100-book list is already getting extensive praise for its breadth, but in case you don’t have time to read them all here are a few select pairings for the refined palette.

David Bowie, aka Space Oddity (1969) – The Gnostic Gospels, Elaine Pagels

Bowie’s first album is a mix of romantic daydreaming and esoteric accusations levied at figures of cultural power. Bowie’s lifelong interest in mysticism begins here, and Pagels’ curated explanation of gnostic texts and belief surely had an effect on his conceptions of power, reality, and man’s celestial ascent.

The Man Who Sold the World (1970) – Day of the Locust, Nathaniel West

This album is both a collection of underworldish characters and a reflection of the desperate desire to illuminate a missing part of the self; what better match than West’s 1939 novel about a man who roams through a series of surreal Hollywood scenes, whose themes “deal with the alienation and desperation of a broad group of odd individuals who exist at the fringes of the Hollywood movie industry”?

Hunky Dory (1971) – Earthly Powers, Anthony Burgess

Earthly Powers, whose you’ve-never-heard-of-it quotient is high, sees Burgess reckoning with a century of change and innovation through the eyes of Kenneth Toomey, who recounts the social and cultural changes for each of his 81 years on Earth. Likewise, Hunky Dory‘s subject matter draws from Bowie’s predecessors and contemporaries and spans the 20th century of culture, from its cover referencing Marlene Dietrich to the futuristic fusion of cinema and space exploration in Life on Mars? Furthermore, the album is anchored by the ode to artistic reinvention, Changes.

The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars (1972) – The Outsider, Colin Wilson

Ziggy represents the height of Bowie’s fascination with the Nietzschean Übermensch, a concept that extends to the figures profiled in Wilson’s study of creativity and isolation. Beyond illustrating the essential otherness of these artists, Wilson questions the fundamentals of a society that allows its greatest thinkers to enter a state of total alienation.

Aladdin Sane (1973) – The Leopard, Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa

Aladdin Sane tears the Ziggy/Übermensch from the heavens of rock stardom and hurls him into an apocalyptic wasteland of American pop culture. Meanwhile, The Leopard follows a nobleman caught in the midst of a revolution from which will emerge a new era. Despite their stylistic differences both are meditations on the loss of prestige, the possibility of eternity, and the malleability of human society.

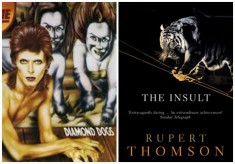

Diamond Dogs (1974) – The Insult, Rupert Thomson

The natural counterpart for Diamond Dogs is 1984; after all, Bowie had envisioned it as an operatic adaptation of Orwell’s book. But for a subtler pairing check out The Insult, which begins with protagonist Martin Blom being shot in the head in a supermarket parking lot. After his recovery he can only see at night—but his doctors insist he is completely blind and delusional. Insult follows Blom’s journey through the sinister underworlds of his hometown where the machinations of various evil plots play out; Diamond Dogs provides an ideal dystopian soundtrack.

Low (1977) – The Divided Self, R. D. Laing

Bowie wrote Low, the first album in the Berlin trilogy, as a synthesis of his own mental torment with addiction and the woes of post-WW2 Europe. Laing’s The Divided Self explores mental illness and psychosis through the lenses of philosophy and existentialism, focusing on the individual who “cannot take the realness, aliveness, autonomy and identity of himself and others for granted.” Low itself is divided into two parts, one a progressive-pop exploration of confusion and anguish, the other an experiential series of sounds conjuring a variety of moods, dreams, and epochs.

Heroes (1977) – The Quest for Christa T., Christa Wolf

Heroes makes quite a few references to another book on Bowie’s list, Alberto Denti di Pirajno‘s A Grave for a Dolphin; however Quest for Christa T is so ideologically similar that it should be in the liner notes. In it a young woman recalls her friend, Christa T., an apparently “good citizen” of East Berlin, who only really feels alive through dreams and imagination as recorded in her stories and diary. The idea that an individual could subvert the USSR’s power in such an invisible yet powerful way led to the book’s immediate censure in East Germany. Likewise Bowie’s album redefines the power of art and dreaming as an act of rebellion, even if “just for one day.”

Let’s Dance (1983) – Nights at the Circus, Angela Carter

Let’s Dance is Bowie’s flashy, gratuitous ode to the spirit of the early 80’s. It manages to sneak in some of his more political tunes (such as China Girl if you believe this conspiracy-esque essay), but was imagined primarily as a vehicle for hits. What better to complement it than Angela Carter’s colorful and absurd Nights at the Circus, with its own political confusion?

Outside (1995) – White Noise, Don DeLillo

I can never listen to outside without being reminded of the opening to Lost Highway. Bowie’s first work with Brian Eno since Low, Outside broadcasts from the intersection of art and horror, and the strange swell of mid-90s hedonism harkening to the glam era and Bowie’s golden years. White Noise is Outside’s spare literary counterpart, tapping into the same questions of how art distorts reality and how future artists create sinister empires of meaning by tampering with the work of their forebears.

Amy Conchie is assistant to the publisher at Melville House.