May 1, 1920

The Apocalypse is here, and it’s dystopian

by Greg Hrbek

Available for purchase here

In her 1965 essay “The Imagination of Disaster”, Susan Sontag discussed the meaning and power of the catastrophic imagery of science-fiction. The thesis of her argument has now become a trope of pop-cultural psychoanalysis: “we live under the threat of inconceivable terror,” and science-fictional disasters “normalize what is psychologically unbearable, thereby inuring us to it.” Back then, the terror was of a civilization-ending exchange of nuclear weapons. Today, our terror is a little different. We don’t fear the instantaneous end of everything; we fear a gradual end, the steady slide into a state labeled, in the marketplace for stories, as dystopian/post-apocalyptic. That’s how my book is classified, tagged, and shelved.

Is the world of my novel a dystopia? Strictly speaking, that means “a society characterized by human misery.” In fact, the world of the book is no more dystopian than the one we live in now. In the future I envision, we are not living in misery. We are living in a condition of uncertainty, in a perpetual fear of attack and of some final collapse. But we aren’t miserable in the sense that the characters of Cormac McCarthy’s The Road are miserable, struggling every day to survive in a world thrown back to the primitive. But it sort of depends on what you mean by us. Because in my book, in an alternate-universe America, a million Arab-Americans are living in internment camps on the Great Plains, where opium addiction is rampant and drone strikes are commonplace. So, I guess you could say there’s a dystopia here. It’s just not being lived by everyone.

*

As for the Apocalypse. To borrow a phrase from the Oxford English Dictionary, it’s in “weakened use.” Not to say that literary apocalypses are a dime a dozen. Just: the Apocalype isn’t what it used to be. And I’m not referring to the original meaning of the word (which has to do with revelation). I’m talking about scale—or, degree of disaster.

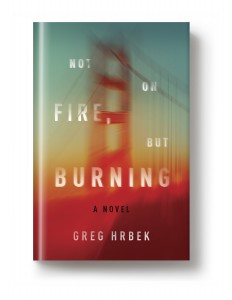

My book begins with what might be the use of a nuclear weapon by Islamosfascists. No one’s sure. It could also be a meteor, an alien death ray, or the anger of God. The ambiguity is perfectly captured in the cover art by Adly Alewa, who uses no conclusive imagery, but renders the hypocenter in the colors and textures of a dream-holocaust. Ground Zero, in this story, is not the World Trade Center. It’s the Golden Gate Bridge. The physical effect of the “attack” (which, in the world of the story, comes to be known as 8/11) is less like Lower Manhattan in 2001 than Hiroshima/Nagasaki in 1945. Destruction of a city. Deaths in the tens of thousands. It’s a catastrophe, it’s a tragedy. But, in the grand scheme of things, the area of effect is very small.

When I was a kid with a basic understanding of the world (1974–1985), my concern was that the ICBMs would come out of the sky like rain, and a wave of nuclear fire would incinerate America from coast to coast. Apocalypse had one meaning: the immediate end of everything. There might be a few survivors wandering around—like the father and son in The Road—but there certainly wouldn’t be any structure or infrastructure. Once it happened, nothing was ever going to be even remotely the same again. But, in the post-8/11 world of my story, life continues pretty much as it did before. Yes, anxiety and racial tension are high (and like I said, there’s that thing about a million people confined and suffering out of sight), but overall there’s Internet and TV, children go to school, adults go to work, people drive their cars and talk on mobile phones. So, how exactly is this post-apocalyptic?

*

But there is a more significant issue at the heart of these questions about a novel–a book that might simply be mistakenly categorized; or perhaps purposely miscategorized to gain some visibility via a not-illegitimate but nonetheless tangential connection to a vogue of the market.

The French philosopher, Jean Beaudrillard, made the postmodernly ironic assertion back in 1991 that the Gulf War did not take place. I think it can be said, in the same spirit, that The End has already occurred. We’ve already been through the Apocalypse. We’ve been writing fictions about this state of affairs for some time now and obsessively consuming the stories—and what we think we’re doing is what Sontag told us we were doing: inuring (maybe even inoculating) ourselves to the future unthinkable. But really what we’re doing is denying the circumstances of the present.

What we’re doing is this: We are reading books and watching movies that replay, in a virtually endless series of metaphorical disguises, the American Apocalypse, while the populations of Iraq and Syria (and so on) live in actual unfolding states of dystopic implosion.

*

I won’t make believe I don’t understand the allure of fictive disaster. I grew up impassioned by the destruction-mythologies of postwar Japan and America: the science-fiction cinema of nuclear fear. To my child’s mind, there was nothing more aesthetically thrilling than monsters laying waste to major cities and taking down historic landmarks. What do you get, as audience, from the sight of a stop-motion animated model of an octopus wrapping its tentacles around a miniature simulacrum of the Golden Gate Bridge and squeezing? You get the existential double-exposure of termination and continuance. That’s the state we live in now. Because the monster finally did come (in the form of a jet plane piloted by atavistic zealots) and The End happened and the resultant shockwave of Dystopia has hit.

What we want now are stories about it.

Tell the story in a new way, just don’t unnerve us too much or make us look too closely at the reality beyond our own borders and make us feel too responsible for it. How about, the world has been burned up by fire, or we’re dying from thirst, or we’re drowning in water, or the zombies are everywhere, or the aliens are invading, or the gas has run out. A scenario that will evoke our sense of trauma without engaging our consciences too directly. Nostalgias of the most profoundly twisted variety camouflaged as cautionary prediction. Ultimate message: It’s a scary idea, but rest easy, it hasn’t happened yet.

Except it has.

So maybe my book is in the right category after all. Because, even though it’s set in the future, it isn’t about the future at all. It’s about the present.

Greg Hrbek is the author of NOT ON FIRE, BUT BURNING (Melville House, 2015). He won the James Jones First Novel award for his book The Hindenburg Crashes Nightly, and his short fiction has appeared in Harper’s Magazine, The Best American Short Stories, and numerous literary journals. He is writer in residence at Skidmore College.