January 15, 2015

The Art of the Novella challenge 10: The Distracted Preacher

by Jonathan Gibbs

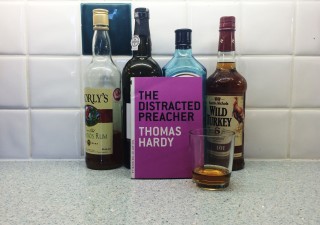

Title: The Distracted Preacher

Title: The Distracted Preacher

Author: Thomas Hardy

First published: 1879

Page count: 98

First line: Something delayed the arrival of the Wesleyan minister, and a young man came temporarily in his stead.

Oh, Thomas Hardy, Thomas Hardy.

I haven’t read Thomas Hardy in decades, or not the prose, at any rate. If the novels – or the major ones: Mayor of Casterbridge, Tess, Jude, Far From the Madding Crowd – were mainstays of my teenage years, now they languish up high on my bookshelves, and I think of them at least in part through Helen Simpson’s marvellous short story ‘Heavy Weather’ – about two run-ragged middle-class parents on holiday in Hardy Country, squabbling over who has found the most time to read among all the fraught child-wrangling. Recently I have read some of the poetry, which makes this almost a reverse of my experience with Baudelaire, whose novella Fanfarlo I read earlier in this novella project. So I turned to The Distracted Preacher with interest, and nostalgia, and high hopes.

High hopes for what? For a dose of grim and fatalistic rural naturalism, perhaps, from this humbler, less programmatic English Zola. Well, if reading The Distracted Preacher has taught me anything, it’s that reading with false expectations brings a productive tension to the proceedings but not one that pays off well. The Distracted Preacher is a comedy – or a comic tale according to the jacket copy, but I tend not to read that before I read the book, clearly preferring to come armed with own prejudices rather than those of the publisher. A comic tale, then, though alas not a particularly funny one.

The preacher of the title is Mr Stockdale, who arrives at the small English village of Nether-Moynton, on the country’s south coast, with the best intentions of fitting in and doing good, but finds himself bamboozled by his landlady, the “enkindling” Lizzy Newberry. The comedy in the narrative, such as it is, comes from Stockdale’s delayed realisation, slightly behind our own, that Lizzy is fully involved in the smuggling operations by which the villagers make their living. She goes out at night covered up in a man’s coat to set signals for the boats coming across from France; he follows her perturbed; he confronts her; she dissimulates; he gibbers. They love each other, but neither can understand why the other won’t give up their silly predilection for criminality/morality so they can both be happy.

Let us cast a younger Hugh Grant as Stockdale, and I suppose a younger Nicole Kidman would have jumped at Lizzy. It is possible, in fact, that the comedy of Lizzy’s character would come across better on screen than on the page; there is something childishly inscrutable about her, as this selection of dialogue shows, taken from when Stockdale first confronts her:

“I am only partly in man’s clothes,” she faltered. “It is only his great-coat and hat and breeches that I’ve got on, which is no harm, as he was my own husband; and I do it only because a cloak blows about so, and you can’t use your arms. I have got my own dress under just the same – it is only tucked in.”

And again.

“I have only a share in the run,” she said.

And once more:

“I don’t do it always. I do it only in winter-time when ‘tis new moon.”

Count those onlys. Now decide: is she being pert or petulant? Are these the words of an ironical and flirtatious woman, toying with her befuddled beau, or those of someone simply too dim to realise the effect her words are likely to have on the man she loves?

In basing his whole story around the tension thrown up by this odd couple, Hardy is pushing us towards one narrative crux: who will yield? If he yields, and turns smuggler, then it turns into a romp. If she yields, and turns respectable, then it’s a dull morality tale. If neither of them yields, or one of them dies, then we throw the book away in disgust.

It’s this kind of zero-sum game that points up a possible defect to the novella form. If Hardy had expanded his canvas to take in the wider situation of the villagers who are driven to crime by high taxes, or the customs officials who are painted as foolish, vindictive baddies, then we would have something more to go on, and the will-they/won’t-they reductiveness of the plot would matter less. But he doesn’t, and we don’t, and there we are.

One other thing springs to mind as something that maybe comes between the book and us, reading it today: smuggling itself. Smugglers are a huge part of British folklore; they are like pirates – baddies we love to love. Think of Jamaica Inn, Moonfleet, Kipling’s poem ‘Smuggler’s Song’, with its imprecation to “Watch the wall, my darling, while the Gentlemen go by”. There’s an implicit romance to smuggling in these fictions, whatever their morality, that I think is just alien to us now.

What is smuggling? It’s dodging taxes, and while I wouldn’t be so sententious as to suggest that we’re all somehow above such immorality these days, I do think smuggling’s lost its benign aspect. These books are all about local communities outwitting local bailiffs, like Robin Hood dodging the Sheriff of Nottingham, doing what’s needed to get by. In contemporary terms, once you’ve discounted smuggling of actually illegal goods (drugs) and people trafficking, then I suppose what you’re left with is cigarette smuggling, which though it apparently costs the British taxpayer some £2bn a year is unlikely to turn up in a romantic novella plotline any time soon. It’s just too drab a subject to attach any glamour to. I suppose the closest approximation to the role of smuggling in The Distracted Preacher is the low level marijuana growing in films such as We’re The Millers or, in the UK, Saving Grace. I haven’t seen either, but then I’d be unlikely to buy a ticket for The Distracted Preacher either, Grant and Kidman or no Grant and Kidman.

Jonathan Gibbs is the author of Randall, or The Painted Grape, published by Galley Beggar Press. He tweets as @Tiny_Camels and blogs at Tiny Camels