January 29, 2015

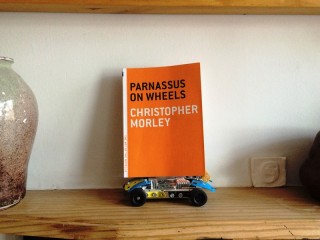

The Art of the Novella challenge 12: Parnassus on Wheels

by Jonathan Gibbs

Author: Christopher Morley

First published: 1917

Page count: 142

First line: I wonder if there’s not a lot of bunkum in higher education?

Part of this project, I said out the outset, was to open up my reading habits to pleasures as yet unknown, as well as to those I know from reputation, or only in part. Here is a case in point for the former. I’d never read Christopher Morley, neither had I heard of Parnassus on Wheels, though its sequel The Haunted Bookshop probably did ring a vague bell.

But then, somewhere in a Twitter discussion of the challenge, someone said that Parnassus was a personal highlight of the series, an annual re-read I think they said, and so I plumped for it next.

Now, this really isn’t the kind of book I’m ever likely to pick up of my own volition – a comedy of the jovial and bucolic kind, rather like the country idyll at the heart of The Winter’s Tale, but with no darkness to set against it, no bite of satire, no blissful flights of Wodehousian farce. A happy book, and how many of those are there in the world?

I’m not quite sure how Parnassus on Wheels sits in the American canon – is it something everybody reads at some time in their life? Or has its own particular brand of old-fashionedness become itself old-fashioned? There’s a definite Pickwishness about proceedings.

I’m so ill-read in this kind of stuff that my reference points are probably fairly wide of the mark – Little Women? Garrison Keillor? There’s even a touch of the Edward Gorey about Morley’s worldview, once you accept that Gorey’s Gothicism is no more inherently dark than Morrissey’s miserablism.

Suffice it to say that Morley’s book – his first, of very many – is a joy and a hoot, largely because it plays entirely to the gallery. It is a book predicated entirely on the idea that books – proper books, real books, honest-to-goodness stitched-together-from-paper-and-card books – are good for the soul, and that anyone who is in the habit of reading them – which, oh my, is you yourself! (not you, reading this: you’re a damned idiot sucking on the digital teat: but you, reading Melville House’s edition of Parnassus on Wheels) – anyone in the habit of reading, I say, is a Good Person, and destined, if not for the heaven to come, then certainly the heaven on earth that only books can offer. Which is as demonstrably true as any tautology can be.

“Lord!” he said, “when you sell a man a book you don’t sell him just twelve ounces of paper and ink and glue – you sell him a whole new life. Love and friendship and humour and ships at sea by night – there’s all heaven and earth in a book, a real book, I mean. Jiminy!”

(A real book! Hear that, Bezos?!)

That’s Roger Mifflin speaking, by the way, the owner of the titular travelling bookshop, a charming horse-drawn caravan that he drives over the whole of the nation, from Maine to Florida, selling books at farms and villages and getting well-liked everywhere he goes. He is the driving force of the story, an impish and pragmatic proselytiser of the type we tolerate in novels but would hate in real life, but the book’s hero is Helen McGill, a stolidly content New England farmer’s wife – except that the farmer is not her husband, but her brother, and that he’s not much of a farmer, not since he wrote a Thoreau-esque book in praise of the simple life that turned bestseller, such that he now spends his time shamelessly tramping about the county, desporting himself as an homme de lettres, while she stays at home, cooking and cleaning and not realising what she’s missing.

So, Mifflin turns up at their farm in the hope of selling his Parnassus to Andrew – so that he can go off to write a book himself, naturally – and in Brooklyn, in point of fact, so I suppose we must credit Morley with a particularly powerful gift of foresight in that instance…

“New York is Babylon; Brooklyn is the true Holy City. New York is the city of envy, office work, and hustle; Brooklyn is the region of homes and happiness.”

(How does that sound, today, Melville Housers?!)

Helen immediately sees how quick her brother will be to buy it and be off, leaving her to manage the farm singlehanded, so she jumps right in and buys it herself. She deserves an adventure of her own, she says.

What follows is a picaresque, with the minor trials and triumphs that implies, but a novella-length picaresque, which is something of a contradiction. The whole point of the picaresque is that it goes on and go, at potentially interminable length, although – when successful – always at a pace to make that length seem quite reasonable. When you get to page 80 of Parnassus’s 140, however, and find that Helen still hasn’t disposed of Mifflin, who’s tagging along on the start of her travels to show her the ropes, you get the distinct feeling you’re not really going to get the full gamut of those possible adventures.

Morley cuts things short, in other words, making this a story with a fine opening act, and a just resolution, but a whole chunk cut out of the middle. Why Morley didn’t go with the rest of it I’m not sure – the book is crying out to be double the length, and he was certainly a hugely prolific writer in the rest of his career – but in no way does this detract from the pleasure of the book.

If, like me, you like books, you’ll love it, for it is the cross-stitch sampler embodiment of two of your greatest, most private and secret dreams, the sort of whimsical thoughts-to-self you suck on on long train rides like a liquorice stick, that you blow on summer’s afternoon like a bubble pipe… and these are, one, that you might one day run a bookshop yourself, you know, with all your favourite books dispalyed in the window, a pot of coffee ticking over on the counter, and a dog aslumber by the fire, and rosy-faced children dragging their parents in from the pavement to splurge their pocket money on full price hardback editions of classic novels that will help them grow up into strong, intelligent and fearless human beings…

And two, that reading books will help you grow up into a strong, intelligent and fearless human being. When we all know they do nothing of the kind. And thank god. For, if they did, everyone would be at it.

Jonathan Gibbs is the author of Randall, or The Painted Grape, published by Galley Beggar Press. He tweets as @Tiny_Camels and blogs at Tiny Camels