March 18, 2015

The Art of the Novella challenge 17 & 18: The Diamond as Big as the Ritz, and Rasselas, Prince of Abyssinia

by Jonathan Gibbs

Title: The Diamond as Big as the Ritz

Title: The Diamond as Big as the Ritz

Author: F. Scott Fitzgerald

First published: 1922

Page count: 84

First line: John T. Unger came from a family that had been well known in Hades – a small town on the Mississippi River – for several generations.

It’s easy to forget, if you only read the novels, how wacky some of Fitzgerald’s shorter fictions could be. Here we are, in the first line, with a character hailing from the Mississippi town of… Hades. Point taken, sir.

Fitzgerald’s general genius was to transpose the triumphalism of the American daydream from its natural major to the minor key, while keeping all its brilliance. But he also turned out enough stories for four collections in the twenty years of his publishing lifetime and five more after it – and among them were oddities such as The Diamond as Big as the Ritz and ‘The Curious Case of Benjamin Button’

To be honest, this was another one of the stories in the novella series that I’d assumed I’d already read, but no; The Diamond… is like appendicitis, which if you think you’ve got it, you haven’t. No one could read this and not know it. It’s unhinged, deliberately, and threatens to undermine Fitzgerald’s golden reputation as the guy who got close to the ‘very rich’, and knew them for what they were, and somehow saw his way clear to hanging them all by silken ropes only ever of their own making. This one – this story, this book (it’s really just a long story, I think) – reads like it’s written by someone who hates, rather than pities the super-wealthy.

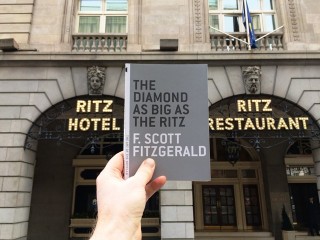

Do we all know it? Do I have to describe it – the boy from the south who goes north to school and then, one summer holiday, heads west to visit with the family of his good, quiet friend, Percy Washington, whose father, he says, is “by far the richest man in the world”, and has a diamond as big as the hotel of the title. (And, yes, I’m writing this in the UK, so that’s a picture of the London Ritz hotel up top, opened five years before New York’s Ritz-Carlton.)

This brag turns out to be the truth. The mountain-sized diamond discovered by Percy’s grandfather in the wastes of Montana is at once the foundation on which the family’s unimaginable fortune rests, and the towering glory of their Shangri La-like fortress home, a hidden valley containing castle, lake and, well…

Full in the light of the stars, an exquisite château rose from the borders of the lake, climbed in marble radiance half the height of an adjoining mountain, then melted in grace, in perfect symmetry, in translucent feminine languor, into the massed darkness of a forest of pine. The many towers, the slender tracery of the sloping parapets, the chiselled wonder of a thousand yellow windows with their oblongs and hectagons and triangles of golden light, the shattered softness of the intersecting planes of star-shine and blue shade, all trembled on John’s spirit like a chord of music.

If happiness writes white, then what does opulence write? It overwrites. No wonder what we remember about Gatsby, among all the splendours of his mansion, is the shirts – and those we remember mostly for the pathos of Daisy’s reaction:

“It makes me sad because I’ve never seen such — such beautiful shirts before.”

Funnily enough, the effort that Fitzgerald expends on coming up with luxuries beyond the wildest dreams of mortal man (solid diamond dinner plates with emerald inlays, a bed that tips you straight into a bath in the morning, surrounded on all sides by aquariums, and with a “moving-picture machine” to entertain you) is duplicated in an eerily similar novella, also in the MHP series, that I picked up and started last week – but put down because I had a Fitzgerald-length train journey ahead of me.

That is Rasselas, Prince of Abyssinia, by Samuel Johnson, he of the Dictionary and the Boswell’s Life of. Let me introduce it now:

Title: Rasselas, Prince of Abyssinia

Author: Samuel Johnson

First published: 1759

Page count: 186

First line: Ye who listen with credulity to the whispers of fancy, and pursue with eagerness the phantoms of hope; who expect that age will perform the promises of youth, and that the deficiencies of the present day will be supplied by the morrow; attend to the history of Rasselas, Prince of Abyssinia.

You’re listening now, right?

Johnson’s Enlightenment fable, published the very same year as Voltaire’s Candide, which it resembles, begins where John T. Unger and Percy Washington arrive: in an earthly paradise built in a valley inaccessible to the outside world, wherein all is harmony and the King’s offspring live endlessly happy lives, until such a time as they are ready to rule.

The sides of mountains were covered with trees, the banks of the brooks were diversified with flowers; every blast shook spices from the rocks, and every month dropped fruits upon the ground. All animals that bite the grass or browse the shrubs, whether wild or tame, wandered in this extensive circuit, secured from beasts of prey by the mountains which confined them.

Meanwhile, in Montana…

The whole valley, from the diamond mountain to the steep granite cliff five miles away, still gave off a breath of golden haze which hovered idly above the fine sweep of lawns and lakes and gardens. Here and there clusters of elms made delicate groves of shade, contrasting strangely with the tough masses of pine forest that held the hills in a grip of dark-blue green. Even as John looked he saw three fawns in single file patter out from one clump about half a mile away and disappear with awkward gaiety into the black-ribbed half-light of another.

Isn’t it delightful! It seems like an exercise you might set a Creative Writing class. 1) fifteen minutes’ free writing in which you must invent and describe the most beautiful place in the world. Start from the best that nature can offer, and allow yourself unlimited cash to improve it. 2) Once you’ve written yourself into a stupor of adjectival excess, spend another fifteen minutes wondering what the hell you might do with this place, in narrative terms. Where can you go, once you’ve built Paradise?

Johnson’s idyll is, pretty clearly, something of a straw man, if you’ll forgive the mixed metaphor. Rasselas, an intelligent and sensitive youth, has tired of his life of ease, and longs to escape to the real world. He finds a comrade in his tutor, the poet Imlac, who ironically enough enlisted to come to the Happy Valley because he was sick of the world and thought that retreat (and boundless luxury) would cure him of it. But when Rasselas presses him on this he admits he would rather be out there than in here. In fact, about a third of the narrative is taken up with Rasselas’ failed attempts to escape his gilded cage, and Imlac’s account of his life in the big wide world.

When the two of them do finally make it out, they are accompanied by Rasselas’ sister Nekayah, and her companion, or lady-in-waiting, Pekuah. What follows is an account of the quartet’s wandering in the world, and their attempts to find happiness, or, in their words, settle on the right ‘choice of life’. They visit Egypt to see the pyramids, rock up at various courts to enjoy the hospitality of their rulers, and converse with a variety of gurus, hermits and astronomers. In between this the three of them sit around and bash all these ideas around: much of what we read comes across as a semi-Platonic colloquy – intelligent, rather dry, but never stilted or confusing. In fact, it is highly epigrammatic, and the book has been held in high esteem as a source of great wisdom.

On the duty of marriage:

“How the world is to be peopled,” returned Nekayah, “is not my care and need not be yours. I see no danger that the present generation should omit to leave successors behind them; we are not inquiring for the world, but for ourselves.”

On the impossibility of ‘having it all’:

“Nature sets her gifts on the right hand and on the left. Those conditions which flatter hope and attract desire are so constituted that as we approach one, we recede from another.”

Or fame:

“Youth is delighted with applause, because it is considered as the earnest of some future good.”

I couldn’t help noticing, though, in reading the book, that talking wisdom (or reading it, for that matter) is not the same thing as living it. The four adventurers go on and on, in their privileged way, and everywhere they go they meet people thought to be happy and successful, yet who aren’t… the king is an idiot, the guru’s philosophy can’t help him when his daughter dies, the hermit can’t wait to get back to town.

The current of frustration that flows under the surface tide of epigrams reminded me of Jack Kerouac’s Desolation Angels, in which he spends a solitary summer fire watching in the Cascades in Washington State, wishing he was in town; and then descends to Seattle and then San Francisco, gets loaded with his friends, and wishes he was back up on the mountain.

Rasselas ends delightfully arbitrarily, in a chapter (the book is made up of dozens of short chapters) entitled ‘The Conclusion, in which Nothing is Concluded’. In a brief envoi, Johnson tells us what the four plan to do next. Pekuah decides she wants to join the convent she stayed in after being abducted by an Arab chieftain. Ah, no, actually she

wished only to fill it with pious maidens and to be made prioress of the order.

Made prioress.

Nekayah loves knowledge most of all, so she plans to study all the sciences and then “found a college of learned women”.

Found a college.

Rasselas himself

desired a little kingdom in which he might administer justice in his person and see all the parts of government with his own eyes; but he could never fix the limits of his dominion, and was always adding to the number of his subjects.

What does this remind me of? Well, apart from the story of the Three Little Pigs, I can’t help thinking of good old Donald Barthelme:

So I bought a little city (it was Galveston, Texas) and told everybody that nobody had to move, we going to do it just gradually, very relaxed, no big changes overnight.

Great wisdom comes from great privilege. The Lives of the Philosophers reads very differently to the Lives of the Artists or Poets, if only for the fact that you’ve got to have the wherewithal to sit on your arse and think all day. Rasselas isn’t strictly speaking a satire – not like Candide is – but there’s something touchingly naïve about those three characters, as Johnson leaves them, stroking their chins and planning their futures. Compare them to Imlac, the common poet.

Imlac and the astronomer [a friend he’s picked up on the way] were contented to be driven along the stream of life without directing their course to any particular port.

That’s how to live, then.

Johnson wrote the book, apparently, in a week. The week between the death of his mother and her funeral. To pay for her funeral.

I have to mention, that the late Mr Strahan the printer told me, that Johnson wrote it, that with the profits he might defray the expense of his mother’s funeral, and pay some little debts which she had left. He told Sir Joshua Reynolds that he composed it in the evenings of one week, sent it to the press in portions as it was written, and had never since read it over.

(From Boswell’s Life of Johnson.)

Which rather explains the abrupt ending.

But what of Fitzgerald? Well, the interesting thing about Rasselas is that, having set up his idyll, and had his hero quit it, no more mention is made of the Happy Valley. The travellers don’t miss it (but then they’re living pretty well despite it, you might say), and they certainly never try to go back there – though I’d bet the Prince’s ‘little kingdom’ will bear a strong resemblance to it, as do the childhoods of our children, when we have them, to the childhoods we had ourselves.

And Fitzgerald’s Happy Valley, what of that? Well, to be blunt, he destroys it. Unlike Imlac, who enters the mountain kingdom knowing he forfeits the right to leave, young John only discovers late on in his visit that he is not going to be allowed to go ever home, and worse. It is young Kisimine, Percy Washington’s sister, with whom John has fallen in love, that lets slip the fact that the children have had guests before, but that they were murdered before the holidays were over.

“It was done very nicely,” Kisimine tells him. “They were drugged while they were asleep – and their families were always told that they died of scarlet fever in Butte.”

So John plans to escape, taking Kisimine (and her older sister) with him, despite his disgust at the rich girls’ dyed-in inhumanity… but in a coincidence of great moment the forces of external reality choose just this time to attack the Washingtons’ citadel. Fitzgerald, having built his Happy Valley, quite literally sends it sky-high – boom! crash! smash! sizzle! – as, I should think, most Creative Writing students would do, having been given 15 minutes to decide what to do with their own personal Castle Miraculous Built of Adjectives. What else is there to do with paradise, once you’ve built it? This, the cynic suggests, is what satire means.

Fitzgerald leaves his three characters lying under the stars, with a chill coming on, and the realisation that the pocketful of diamonds that Kismine grabbed as they fled are actually rhinestones, trinkets she’d kept for fun because she was bored of the real thing. The valley, castle, diamond, wealth… it’s all gone – and you get the sense that these three aren’t about to go bounding off down the hill, like Rasselas & Co., to find out their futures.

In fact here, suddenly, and strangely, the Fitzgerald we know and love – who has been all but absent throughout the sinister but rather glib fairy tale – rears his head. “At any rate,” John says to Kisimine,

“let us love for a while, for a year or so, you and me. That’s a form of divine drunkenness that we can all try. There are only diamonds in the whole world, diamonds and perhaps the shabby gift of disillusion. Well, I have that at last and I will try to make the usual nothing of it.”

That’s a schoolboy talking, remember, to a school-age child. There’s a little more – I won’t spoil the end – but that Gatsby-esque note of exquisite abandon is present and correct. No point following these guys on their travels. They won’t meet any gurus, or astronomers, they won’t even get abducted and carried off to an island on the Nile (or the Mississippi). And even if they did, they wouldn’t glean any wisdom from it. If The Diamond… is in any way a response to Rasselas – and I’d be thrilled to hear from anyone that it was – then this is the lesson we must take from it. There’s the gains of 160 years of progress, right there.

Jonathan Gibbs is the author of Randall, or The Painted Grape, published by Galley Beggar Press. He tweets as @Tiny_Camels and blogs at Tiny Camels