March 25, 2015

The Art of the Novella challenge 19: The Lifted Veil

by Jonathan Gibbs

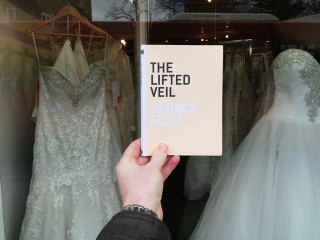

Title: The Lifted Veil

Title: The Lifted Veil

Author: George Eliot

First published: 1859

Page count: 75

First line: “The time of my end approaches.”

Now I’m not particularly an aficionado of ghost stories, or the gothic, or horror, but then nor, it seems, was George Eliot, who is another author I am coming to first in novella form – proof if proof were needed that I didn’t study an English degree at university. Middlemarch – “one of the few English novels written for grown-up people” (Woolf) – sits still on my shelves, gazing balefully down upon me, and, excellent though The Lifted Veil is, reading it has in no way excused me from that particular obligation.

The book fits the bill of the novella form perfectly – it is the story of a life, told in retrospect, in the first person; and not in a comprehensive, biographical way, but obsessively, eyes narrowed, and focusing on one particular aspect which, if it applied to you, you’d write a novella about it too.

The narrator, Latimer, suffers from a double form of second sight – it gifts him occasional flashes of his own future, and it lets him see easily and all the time into other people’s minds. He can make out their thoughts and intentions, though none of them are very happy ones. The more you get to know Latimer, the more you begin to think that the sheer, drear, monotonous awfulness of what he sees in other people is as much down to his morbid temperament, as to theirs. The ‘lifted veil’ is a metaphor for the novelist’s own personal curse – to always see through those around one, always imaginatively and always reductively.

The story opens dramatically enough, with Latimer making a premature declaration of death. You might think of the classic film noir DOA, which has Edmund O’Brien staggering into a police station to report his own murder. Here’s Latimer:

Just a month from this day, on the 20th of September 1850, I shall be sitting in this chair, in this study, at ten o’clock at night, longing to die, weary of incessant insight and foresight, without delusions and without hope. Just as I am watching a tongue of blue flame rising in the fire, and my lamp is burning low, the horrible contraction will begin in my chest. I shall only have time to reach the bell, and pull it violently, before the sense of suffocation will come. No one will answer my bell. I know why.

It’s horrible, and compulsive. For some reason the image of the old man in his chair brings to mind Arrangement in Grey and Black No.1 (a.k.a. Whistler’s Mother). We can imagine the same domestic grey, the same blackness of attire – there’s little more than a decade between the book and the painting – but in fact Mrs Whistler lacks the moroseness, the self-obsession that is a pit deep enough to drown in. (Who is more self-obsessed than the person who can see into the souls of those around him or her? With no mystery to them, what is the point of even talking to, or looking at, other people? No, Whistler’s not right. If anything, the mood of the novella more accurately resembles that of a Munch painting: dour, overpowered, feverish.)

I said that Latimer sees through everyone, but in fact there’s one veil that does not lift for him. Inevitably, it is the one that hides the heart, mind and soul of a young woman, a little older than him, with whom he falls… not into love, precisely, but into an infatuation. This is Bertha (strangely impossible name, today, alas, for a femme fatale), a family friend and the intended bride of Latimer’s elder brother Alfred. Alfred is everything that Latimer is not: handsome, self-confident, loved and admired by their father.

Latimer is, naturally, smitten with Bertha, although the causality of this is ambiguous. Does he fall for her because he cannot read her, or can he not read her because he is blinded by desire? In any case, the reader might at first be similarly affected. Here’s Bertha when he first sees her:

not more than twenty, a tall, slim, willowy figure, with luxuriant blond hair, arranged in cunning braids and folds that looked almost too massive for the slight figure and small-featured, thin-lipped face they crowned. But the face had not a girlish expression: the features were sharp, the pale grey eyes at once acute, restless, sarcastic. They were fixed on me in half-smiling curiosity, and I felt a painful sensation as if a sharp wind were cutting me.

Difficult to know, at this distance, about that ‘sarcastic’. In our strange modern world a sarcastic look as about as genuine an expression of deeply held feelings as you can get. For Latimer, the uncertainty is absolutely delicious. Bertha flirts with him, sometimes maliciously, but at other times seemingly honestly, giving him means to suppose that she loves him more truly than she does his brother.

Then, when he’s ready to tear himself in half over her, it gets worse; he is vouchsafed another vision of his future, a scene from the future in which Bertha is his wife, only now he can read her mind:

Bertha, my wife – with cruel eyes, with green jewels and green leaves on her whie ball-dress; every hateful thought within her present to me… “Madman, idiot! Why don’t you kill yourself, then?” It was a moment of hell. I saw into her pitiless soul – saw its barren worldliness, its scorching hate – and felt it clothe me round like an air was obliged to breathe. She came with her candle and stood over me with a bitter smile of contempt; I saw the great emerald brooch on her bosom, a studded serpent with diamond eyes. I shuddered – I despised this woman with the barren soul and mean thoughts; but I felt helpless before her, as if she clutched my bleeding heart, and would clutch it till the last drop of life-blood ebbed away. She was my wife, and we hated each other.

Oof. Reading this, I wondered about the misogyny of it – Bertha is a harridan to put men off marriage for good – but then Latimer is darkly painted , too. The whole book is, truly, a vision of hell, but it is no glib or distant hell, easily conjured and equally easily dismissed.

Not, as I say, being a big reader of such works – ghost stories and the like – the closest comparison I can bring to bear is that of Poe, but Eliot brings something to bear that Poe cannot: a thickening of the texture of the uncanny, that drags it down, drags back into the heart of man. Poe, in the end, is always fantastical, his twists always twist away from humanity up into something ineffable, something that be explained away or excused. There is something glum, grim, sullenly northern or northern European about The Lifted Veil. Bertha is described as being like Lucrezia Borgia, but also like a “Water-Nixie”, a new word to me, but easily resolvable to a water sprite or Rhine-maiden, “pale, fatal-eyed”.

The tale is dreadful above all because it stays close to home – and that is the ‘realism’ of Eliot, I suppose, her acknowledged mastery of psychological shadings. The story sinks its fangs into a very fundamental fear – the fear that when we are faced with the thing that will do us the most damage (the first bad man, the crumbling cliff edge, the toxic dose) we will reach for it, we will pitch after it, while our useless knowledge flaps hideously around us.

What’s most weird about Eliot’s novella is how it sits so unnervingly between the Gothic and the modern. Frankenstein and Poe are far behind it, but The Turn of the Screw is ahead of it. It can’t be fully reconciled to either tradition – the mark of the true novella? Perhaps it’s no surprise that this was an experiment that Eliot didn’t repeat. (It was published in the same year as her first novel, Adam Bede.) But it shows what she’s about.

Jonathan Gibbs is the author of Randall, or The Painted Grape, published by Galley Beggar Press. He tweets as @Tiny_Camels and blogs at Tiny Camels