July 6, 2015

The Art of the Novella challenge 32: Tales of Belkin

by Jonathan Gibbs

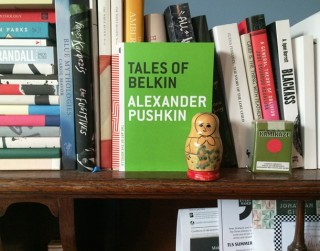

Title: Tales of Belkin

Title: Tales of Belkin

Author: Alexander Pushkin

First published: 1831

Page count: 108

First line: Having taken it upon ourselves to publish the Tales of I.P Belkin, which we offer now to the public, we wanted to append a brief biographical sketch of the late author, and in doing so partly satisfy the justly aroused curiosity of lovers of our national literature.

Now hold on a minute, people. I started this project – this challenge – in good faith. I’ll read all your novellas, I said to Melville House, and I’ll write about them. And I’ve tried to do that, tried to give an honest response to each book as I read it, sometimes drifting into reminiscence or invective, often pronouncing from atop a particular, one-week-only, never-to-be-ridden-again hobbyhorse, and only occasionally descending into something akin to literary criticism. I’ve kept up my side of the bargain. And so have Melville House… mostly.

I raised an eyebrow at Maupassant’s La Horla: do three versions of a short story, even when the three versions are fairly different, and the story itself superb, make a novella? I threw up my hands at Balzac’s The Girl With The Golden Eyes, despairing of its descriptive logorrhea, clunking satire and borrowed-clothes sexiness.

And now this.

Tales of Belkin, by Alexander Pushkin. Five short stories, together with a metafictional ‘Note from the Publisher’, telling us that what we’re about to read are “true stories heard from various people” – heard by I.P. Belkin, a mild and modest landowner of the early 1800s, who wrote them down for his own amusement. There is nothing to link the stories: no common characters or theme or underlying structure to give them form. There’s a ghost story, a tale of military honour, a tale of family dignity, and a couple of love stories. There are outrageous coincidences, it-was-all-a-dreams and subtle character studies.

Belkin himself seems to transcribe verbatim the stories he heard – each story has its own narrator, as indicated in the publisher’s note, and the difference in narrative styles is intriguing. Some narrators tell their stories first-hand, some offer them as retellings; some intrude on their narration, others retire to near-omniscience.

Taken together, however, they are, quite simply, not a novella.

Yet here they are in the Art of the Novella series. Why, Melville House, why?! Perhaps the publishers will point to their note on the inside flap that the work, “first published anonymously, due to the author’s fears of the Tsar’s censors […] would prove such a watershed publication that it has become the namesake for Russia’s most prestigious literary award, the Belkin Prize, given to the best novella of the year”. To which I can only reply, Why, Russia’s most prestigious literary award, why?!

In fact, the Belkin Prize itself is a frustration. There is a website, but it’s in Russian, with no English version. You can find a few winners’ names here and there online, but there’s nothing comprehensive. Are any of the winners available in translation? It would be good to know. I can’t even work out how long it’s been going.

There is some good info on the blog Lizok’s Bookshelf, where writer and translator Lisa Hayden Espenschade tells us that the prize

recognizes the best повесть of the year. A brief digression since the “povest’” category is a little tricky: a loose translation of my Ozhegov dictionary definition calls a povest a narrative literary work that’s less complicated than a novel. When I write about povesti, I usually call them short novels or novellas. For reference, Sorokin’s Blizzard is a povest’ but his Oprichnik book is a novel, at least according to the books themselves. Related words include повествование/povestvovanie, which is storytelling, narrative, or narration.

I particularly like that “less complicated than a novel”. That’s something I could use in my ongoing definition of the novella. It’s not length that differentiates the novel and novella, but the intricacy with which the narrative binds the plot (the interaction of character and event) to the world. In the novella, the blinkers are on, the head is down; the narrative sticks to the facts. In the novel, the shutters are open, and the world is allowed to bleed in, to infiltrate and contaminate – though that contamination works both ways. The world illuminates the novel, and the novel illuminates the world. The novella is a stage set with nothing beyond the wings.

But back to Belkin. I could talk a little about the individual stories, but why should I? I’m here to write about novellas. I could scratch my head over the figure of Pushkin, who we know is the ‘Father of Russian literature’, but is so much less widely read abroad than his descendants, some of whom have struck gold in this novella series, with more to come.

I mean, I’ve tried to read Eugene Onegin, but the rhyme scheme, in English, gets thoroughly in the way of its ‘novelishness’. With little on my shelves covering this field I’ve read Adam Thirlwell on it, and its connection to Tristram Shandy, in Miss Herbert, and I’ve read about Nabokov’s trials with it, and his set-to with Edmund Wilson (and, while we’re at it, why isn’t there a reasonably priced edition available of Nabokov’s all-the-sense-and-none-of-the-poetry translation – perhaps with some of the commentary?) I happen to have seen the opera of Onegin and, for that matter, the opera of The Queen of Spades, based on Pushkin’s story of that name, which opens my Penguin Classics Russian Short Stories from Pushkin to Buida, and which editor and translator Robert Chandler calls “the greatest of all Russian short stories”.

Chandler reminds us that Pushkin wrote the first major works in Russian in a number of genres – from historical novel to narrative poem to verse novel – but there’s nothing in any of this that, for me, makes the case for Pushkin as a worthwhile author to read, rather than simply to tip one’s hat to and acknowledge as ‘the father of them all’, then move swiftly on to Chekhov, Tolstoy, Dostoevsky and the rest.

To be sure, the stories in Tales of Belkin are good ones, mostly. I can live without ‘The Undertaker’ (gothic near-horror) and ‘The Shot’ (another duel! though a million miles from Chekhov’s masterpiece), while ‘The Snowstorm’ is amusing enough to pay its way. The last two stories, however, are better, and seem to point the way far more insistently to the writers that would come after.

‘The Stationmaster’ tilts in the direction of Chekhov, with its tale of a stationmaster – not of a railway station, but a coaching station. He has a beautiful young daughter, who charms everyone she meets, the narrator included, but eventually runs off with a no-good hussar. The strength of the story is in the coda: the last time the narrator passes through the area he learns that the station master is dead, but hears from a boy of the village that “a rich lady”, who can only be the daughter, had visited, and gone to pay her respects at the cemetery. The boy takes the narrator to see it:

We went to the cemetery, a bare place, unsheltered, dotted with wooden crosses, without a single tree to give it shade. Never in my life had a I seen such a graveyard.

“Here’s the grave of the old stationmaster,” the boy told me, jumping onto a pile of sand in which a black cross with a gold design on it had been planted.

“And the lady came here?” I asked.

“She came,” Vanka answered.

Yes, the prose is good – “clear and succinct” as Chandler has it – but it’s the distance at which we observe the emotional pay-off – at third hand, and too late for the stationmaster – that makes it work.

‘The Lady-Maid’ is a love story of an endlessly familiar stamp. Neighbouring landowners have a feud and never talk. The daughter of one wants to see the supposedly dashing son of the other, so dresses up as a peasant girl and waits for him in the woods where he hunts at first light. They meet, and fall in love, but she can’t reveal who she truly is – while still secretly holding “the dark, romantic hope of finally seeing the Tugiobsky landowner at the feet of a Prulichinsky blacksmith’s daughter”. You can guess how it ends. Or it doesn’t much matter how it ends. Either way.

Certainly, there is a sense in these five tales of similarity-in-variety, a sense that the absent Belkin is somehow there in the texts he transcribes – rather as the narrator in Rachel Cusk’s Outline, which I read recently, is somehow there in the stories other people tell her of themselves. Pushkin gives us a step on the way from the nouvelle (e.g. the tales collected in the Decameron) to the novel, from the various, serial plainsong of the one to the complex polyphony of the other. His is an organising presence. And I do doff my cap to him, but with no Russian to read him in, I doff my cap retreating, and head off to hang out with his children.

And it’s not a novella.

Jonathan Gibbs is the author of Randall, or The Painted Grape, published by Galley Beggar Press. He tweets as @Tiny_Camels and blogs at Tiny Camels