July 16, 2015

The Art of the Novella challenge 33: The Duel (Kuprin)

by Jonathan Gibbs

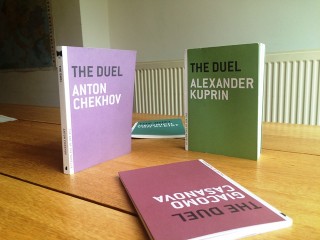

Author: Alexander Kuprin

First published: 1905

Page count: 306

First line: The sixth company’s maneuvers were winding down, and the junior officers were checking their watches more frequently and with greater impatience.

From the novella that’s not a novella, because it’s a collection of povesti or tales, to the novella that isn’t because it’s over 300 pages long. Or it is. Or isn’t. Clearly Melville House are throwing down a gauntlet here. The Duel comes in at 92,437 words – or nearly two Gatsbys, to use the standard measure – while, to take an example entirely at random, my own book, Randall, or The Painted Grape, runs to 96,633 – and that, my friends, is most definitely a novel, and I’ll fight anyone who says it’s not.

The contention, clearly, is that there is more to the definition of the novella than length, which I’ll accept, with the caveat that whatever it is the novella does, that makes it a novella, it is most easily or successfully do-able over a certain length, and that length is well under 90,000 words.

Following my recent take on Pushkin’s Tales of Belkin, I had an interesting Twitter response from Katia Bowers, Assistant Prof of Slavic Studies at University of British Columbia, who defended Belkin as a novella, where she defined a novella as a “less structured experiment with novelistic form”, pointing out that it came from a time when Russian writers were “working out what novels are, what novelistic form is”. She also called it, experimentally, a “pre-novel”, which is another reminder that Russian literature as we know it was a very late starter. By the time Pushkin wrote his book, English literature had already had Defoe, Richardson, Fielding, Sterne, Scott and Austen.

Katia’s defence does make me think that Belkin probably does belong in the novella series (to sighs of relief from Melville House, no doubt), but as a seminal experiment, rather than a central exemplar, a sideshow rather than a tent pole. Only seventy years separate Tales of Belkin and Alexander Kuprin’s The Duel, but seeing as those seventy years contain all of Tolstoy, all of Dostoevsky, all of Chekhov and all of Gogol, you might as well say that they are separated by nothing less than the full, magnificent flowering of Russian prose fiction.

Reading Kuprin from the early 21st Century, what strikes me is how forward-looking it is, how close it is to the cynical, scabrous slant of the new century it rolled in on the back of. (It’s not modernist in its style, particularly, indeed far less so that Kate Chopin’s earlier The Awakening.) In its brutal-comical take on the military life it’s only a hop and skip away from Catch-22, and takes Hašek’s Good Soldier Švejk happily in its stride to get there. In its willingness to plumb the depths of personal despair – to write it, rather than simply show it – it’s at least as close to Sartre as it is to Dostoevsky.

But it’s this very depth and texture of affect that tilt me towards positioning it as a novel. It’s got too much going on to be a true, or a pure novella.

There is no true or pure novel, of course – it is its promiscuity, its avariciousness and indifference, its mongrel air that mark it out as a genre. If we are going to define the novella in opposition to the novel, we’ve got to look at the outline each of the two forms makes, the way the novel’s borders are porous and badly guarded, happily welcoming foreign antibodies and invading armies and integrating them with the same equanimity, where the novella is closed and armed and intent on itself. It is tensed. It is ready to fight its corner. No wonder so many of them are called The Duel.

The Duel’s setting is a remote garrison of the Russian army. Far from any actual fighting, the soldiers’ only occupation is endless drills and occasional inspections. They spend their time gambling, drinking and carrying out torrid affairs with the wives of other officers. The book’s hero is Romashov, a thin, shy ungainly Second Lieutenant who is intelligent enough to be dissatisfied with his lot, but not really clever enough to change it, and certainly not good enough a soldier. In the opening scene, a group of bored officers are using a tailor’s dummy for sabre practice. Romashov has a go, and nearly slices his hand off.

For this man, the lack of activity breeds a particular kind of misery. He wants out, but can’t get out. He’d rather do anything than get drunk again with the other idiot soldiers, but can’t stop himself – come evening, drinking games and stupid jokes are a better option than his crappy room and crappier thoughts. He keeps himself going in his misery by pining for Alexandra Shurochka the wife of a superior officer. She knows he fancies her, knows full well too that her husband is a drip – he’s cramming for his entrance exams for the general military academy, which he’s failed twice, while she knows all the answers off by heart, sitting there in the room with her needlework – but she still doesn’t quite feel strongly enough about Romashov to have an affair with him.

Kuprin gives us full access to Romashov’s thoughts and world view, but not Shurochka, and this makes her a fascinating and substantive character. Is she eminently sensible to ignore Romashov’s doe eyes, or cold and calculating? It’s up to the reader to interpret her. She certainly has him wrapped around her little finger:

“Listen, Rommy: really, don’t forget us. I have only one person I can be myself around – that’s you. Do you understand? Only, don’t you dare make those sheep’s eyes at me again. Because then I won’t want to see you. Please, Rommy, don’t even think it. You’re barely even a man.”

Later, at a group picnic, she takes him off into the woods to lie in the grass and exchange sweet nothings. They talk of love, she confesses her love – for today at least – kisses him, but still tells him how pitiful he is.

The bonfire, wherever it was, could not be seen from where they were, but every once in a while, a red light flickered over the tops of the closest oaks, like the reflection of distant summer lightning. Shurochka stroked Romashov’s head and face quietly; when his lips found her hands, she pressed her palm to his mouth herself.

And again.

She threw her arms around his neck and pressed her hot moist mouth to his lips, her teeth clenched, pouring her whole body from feet to breast into his with a groan of passion. To Romashov, it was as if the black trunks of the oaks swung to one side, and the earth floated to the other, and that time stood still.

The hand on the mouth. The kiss with clenched teeth. It’s those actions that make her, for me. As a character, she is opaque (we don’t know if the oaks swung this way, the earth that way, if time stood still for her), but infinitely open to interpretation.

“Being close to you excites me. But why are you so pitiful?”

To which Romashov can only fling himself on the ground, when she makes to leave, and hold her about the legs, and cry:

“Sasha, Sashenka! Why won’t you give yourself to me? Why? Give yourself to me!”

Oh, we know why. We know why.

Again, that title: We know a duel is coming. We can guess what it will be about. What Kuprin does with these characters and that event is unforgettable: alive, but incidental, produced by character not plot – but it is also light. It’s not the treatment that would work with a novel.

Let’s think again about plot and the novella. Here there is an insistence on plot, but also on a lightness of plot. A novella is a pebble dropped in a small pool. The ripples don’t reach further than the banks. There are no echoes, no ramifications beyond them. You can’t have an echo where there is nothing to echo off.

The other element of the book that does make it feel more novel- than novella-ish is the presentation of Romashov’s interiority, the banking up of his misery and despair and self-hatred until it reaches existential proportions.

Romashov held his hands in front of his face and looked at them with surprise, as if for the first time. “No. None of it is me. And if I pinch myself on the hand… like so… that’s me. I see my hand, I hold it up – that’s me. This, that I’m thinking right now, that’s also me. And if I decide to go for a walk, that’s me. And the person who stops – that’s me too.

“How strange, how simple and how incredible. Maybe everyone has such an I? And maybe not everyone has one? Maybe I’m the only person who has one.? And if that were really the case?

Of course, this kind of interiority doesn’t mean this can’t be a novella. But this and the tragi-comic treatment of the military life, and the sections in which Kuprin seems to use his situation to build out struts and girders to the rest of the world… to make the specific general… (“Save for a few careerists and men of ambition, the majority of the officers treated their military service as if it were a period of enforced labour, loathsome and unwarranted…”)… all of this put together gives the book more scope, more ambition, a wider purview than would be allowed in my restrictive definition of the novella.

The story: something glimpsed.

The novella: something anatomised.

The novel: everything, if only by implication.

The novel form works on the unspoken assumption that the text could go on growing, sentence after sentence, extending on both the axis of space (taking in more of the world, inside and out) and the axis of time (taking in more of what has and will happen), until it encompasses literally everything. The novel implies the whole world. It is universal in scope, the novella universal only ever in aspect. That is why symbolism is so important in the novel, less so in the novella. It suggests ways the given narrative could be expanded and extrapolated. Symbolism implies the unseen, the unmentioned, the unsupposed. It seems to present echoes to the ear of the reader, from which the reader builds the invisible structures out there beyond the text, off which the words might have bounced. Back to The Duel.

The Duel is, undoubtedly, a goodie, managing to wind up the nothingness of provincial military life until a kind of tension is achieved. It is never quite gripping, never quite absurd. It has indelible moments that refuse to grow into scenes. It has characters to spare (and Chekhovian characters at that) – not just Romashov and Shurochka, but the bellicose Bek-Agamalov; the alcoholic, Dostoevskian Nazanski; Lieutenant Burden, with his pathetic private zoo; even the general who comes to inspect them neatly sidesteps the reader’s expectations as if they were a clumsily wielded sabre. Above all, it has a protagonist – Romashov – who holds it all together, who deserves a whole novel, but who is denied it, as he is denied so much else. In fact, perhaps it is he, with his pitiful lack of ambition, who stops this being a novel! Perhaps it is Shurochka, “young, smart, good-looking, I know this. Not beautiful” Shurochka, from inside that text, who made that decision, who called it, and made the right call.

Jonathan Gibbs is the author of Randall, or The Painted Grape, published by Galley Beggar Press. He tweets as @Tiny_Camels and blogs at Tiny Camels