January 6, 2015

The Art of the Novella challenge 8: Jacob’s Room

by Jonathan Gibbs

Author: Virginia Woolf

First published: 1922

Page count: 212

First line: “So of course,” wrote Betty Flanders, pressing her heels rather deeper in the sand, “there was nothing for it but to leave.”

In the stack of MHP novellas Jacob’s Room show up for the thickness of its spine: chunky, solid, ever so slightly forbidding, and so very much going against the residual and no doubt unhelpful image of Virginia Woolf – from her photos if nowhere else – as fey and ethereal, even her wryness softened to a genteel ‘Who, me?’ puppyishness. And then there’s the grey slab of its cover, which seems, for much of the book, to misrepresent its contents, which are so fantastically effervescent, so alive, always moving, never still. The cover, you think, reading it, looks like a gravestone.

I hadn’t read Jacob’s Room before, and so I came to it perhaps a little from the wrong direction. After all, this was the book in which Woolf comprehensively broke the mould of the realist novel and worked out the processes that she would later refine in the more famous books, the ones that I had read.

So it paved the way for Mrs Dalloway, To The Lighthouse and The Waves, but is Jacob’s Room worth reading? Well, yes, of course. It is an often scintillating read. It might not be her most experimental book (The Waves presumably is that, though annoyingly I can’t find my copy of it in the house; I remember my mother telling me it’s one of those books that are best read at a certain age, and I’d like to go back and test that idea) but I think it must be her freest.

It presents a life – that of young Jacob Flanders, Cambridge undergraduate and man-about-Europe – from being a “tiresome little boy” to something like adulthood, but without any of the usual accoutrements, or furniture, or scaffolding of the novel. It slips from scene to scene, from style to style – close third person to interior monologue to prose poem – from character to character. In theory all these differing perspectives are there to give us a kaleidoscope vision of Jacob, as seen by those around him, who know him, and love him, or are just sat on the bus opposite him for a few minutes, but the book is even less structured even than that.

If one of my original theories of the novella was that it is a form predicated on concision and reduction – a pruned novel, self-sufficient, with nothing implied beyond its frame – then this might be an anti-novella. The text of Jacob’s Room might be thought of as what is left after a much bigger novel has been ruthlessly edited – except that this is what was discarded, not what was kept. It is the sweepings of the cutting room floor. It is a file of murdered darlings.

And what darlings they are. My copy is a welter of underlinings. Here’s a couple of paragraphs that, though consecutive, got marked for entirely separate reasons:

The Scilly Isles were turning bluish; and suddenly blue, purple, and green flushed the sea; left it grey; struck a stripe which vanished; but when Jacob had got his shirt over his head the whole floor of the waves was blue and white, rippling and crisp, though now and again a broad purple mark appeared, like a bruise; or there floated an entire emerald tinged with yellow. He plunged. He gulped in water, spat it out, struck with his right arm, struck with his left, was towed by a rope, gasped, splashed, and was hauled on board.

The seat in the boat was positively hot, and the sun warmed his back as he sat naked with a towel in his hand, looking at the Scilly Isles which—confound it! the sail flapped. Shakespeare was knocked overboard. There you could see him floating merrily away; with all his pages ruffling innumerably; and then he went under.”

The Shakespeare, of course, is a book; Jacob is sailing to the Scilly Isles from Cornwall with a university friend – and the extract shows the comedy of the writing, as well as its dismissal of traditional narrative and, in the first paragraph, the reaching, reaching, for description, for some adequate form of description, to keep throwing words at the world until it yields itself, in some way, up. A particular patch of water being compared to a bruise – now, if I, as a writer, could come up with one simile like that in my career, I’d consider myself blessed, or brilliant.

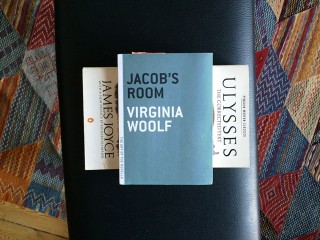

It’s fascinating, particularly, to read Jacob’s Room in tandem with Woolf’s diaries, in which she records her work on it even as she is reading Ulysses for the first time.

Wednesday 6 September moves from her proofs of her book (“The thing now reads thin and pointless; the words scarcely dint the paper; and I expect to be told I’ve written a graceful fantasy, without much bearing upon real life”) straight to Joyce (“I finished Ulysses and think it a mis-fire”). You get something of the confidence of Woolf as a writer that her unhappiness with her own work is in no way born of her trembling before what is generally considered one of the greatest novels of the 20th Century.

But Jacob’s Room does stand up against Ulysses. If it’s not a more radical work, then you might say it’s more courageous. Both of them reject conventional characterisation, conventional plotting, conventional mimesis – all the stuff Woolf rails against in her essays (viz ‘Modern Fiction’: “Is life like this? Must novels be like this? Look within and life, it seems, is very far from being ‘like this’. Examine for a moment an ordinary mind on an ordinary day. The mind receives a myriad impressions – trivial, fantastic, evanescent, or engraved with the sharpness of steel. From all sides they come…”).

Unlike Ulysses, however, Jacob’s Room isn’t underpinned – and, underwritten – by the solid framework of myth, of pre-existing literature. The gaps in our expectations of what literature might be (and try to think what it must have been like to read these books in 1922) are filled, in Joyce, by Homer, and, well, pretty much everything else. With Woolf, there is nothing underneath, no safety net. The gaps in the books are gaps in life.

Writing this piece, I was humming and hawing over whether I really considered Jacob’s Room a novella, rather than a novel. Certainly, it’s a book to define as much by what it’s not, as what it is. I like the capaciousness of the novel, and certainly no theory of the novel would think to exclude this book, whereas it’s possible that some strict theories of the novella would think it too baggy, not necessarily in its extent, but in its diffuseness.

But then I thought, perhaps it’s best thought of neither a novel or a novella. Perhaps it’s an essay. Certainly it contains plenty of material reflecting on its own processes:

The strange thing about life is that though the nature of it must have been apparent to every one for hundreds of years, no one has left any adequate account of it. The streets of London have their map; but our passions are uncharted.

And, a dozen pages on:

For example, there is Mr. Masefield, there is Mr. Bennett. [He of her essay ‘Mr. Bennett and Mrs. Brown’.] Stuff them into the flame of Marlowe and burn them to cinders. Let not a shred remain. Don’t palter with the second rate. Detest your own age. Build a better one.

This is not mere novel-writing. This is Woolf burning her thoughts direct onto the page.

Yes, Jacob’s Room is an essay, it’s an attempt at something. Perhaps, even, it’s an illustrated essay, and the fictional elements, the stories and characters, are the illustrations. This makes it more contemporary than ever. Jacob’s Room: An Essai. I like that.

Jonathan Gibbs is the author of Randall, or The Painted Grape, published by Galley Beggar Press. He tweets as @Tiny_Camels and blogs at Tiny Camels