February 21, 2014

The rise of the literary anti-heroine

by Sadie Mason-Smith

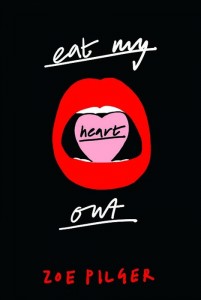

Eat My Heart Out by Zoe Pilger

A bevy of recent books feature female main characters who avoid falling into the role of caregiver or even quirky love interest. Instead, Sarah Hughes has noticed a new cultural trend: women are focusing less on romance and more on having a good time.

Hughes reports in the Guardian that authors are writing more characters like Zoe Pilger’s Ann-Marie, who “spends her time careening through London while trying to get as wasted as possible and discover the meaning of life.” Fellow writers Helen Walsh, whose latest novel The Lemon Grove features a middle-aged woman fantasizing about seducing her daughter’s boyfriend, and Emma Jane Unsworth, whose novel Animals has been called “Withnail for girls,” are also embracing an antihero for a heroine. However, writing such an opinionated main character can cause reprisals in reviews. Pilger explains:

“Some reviewers have said Ann-Marie is unlikeable, damaged and lost, but I see her as strong. She’s frustrated at the social facades that make up so much of daily life. If you’re a man, you can be a disaffected antihero and have a proper existential crisis, but if your character is female, her concerns are dismissed as the petty stuff of personal life.”

Author and critic Roxane Gay recently lambasted the idea of “likability” as a desirable quality in a main character on BuzzFeed:

“Writers are often told a character isn’t likable as literary criticism, as if a character’s likability is directly proportional to the quality of a novel’s writing. This is particularly true for women in fiction,” Gay says. Gay prefers a more alive version of a protagonist. “I want characters to do the things I am afraid to do for fear of making myself more unlikable than I may already be. I want characters to be the most honest of all things — human.”

These new anti-heroines are definitely human, with all the inherent flaws in the condition. Hughes feels that these women appear as “part of a wider cultural change in which the comfortable romantic lies of a Bridget Jones or Carrie Bradshaw are replaced with something rougher, and perhaps truer.”

Unsworth explains her motivation for writing such daringly human main characters as a need for “alternative” narratives. “I felt as though there weren’t many stories that featured women just dicking about, and I also wanted to address the idea that if you keep partying, you’re an idiot or a failure – like there’s just one way to live, which there isn’t.”

Sadie Mason-Smith is a Melville House intern.