July 18, 2014

The Very Hungry Caterpillar has OCD: When adults find meaning in children’s books

by Julia Fleischaker

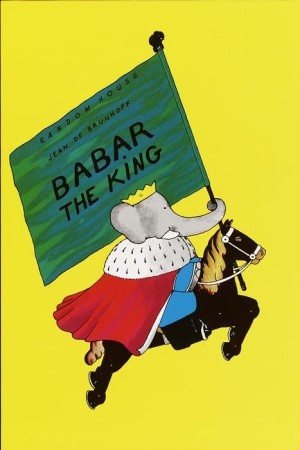

Most of us remember Babar as a charming series of children’s books. But some people also see it as an endorsement of colonialism. Image via Random House

Are the Babar books simply the charming story of an orphaned elephant who becomes king, or are they a justification of colonialism? Is The Very Hungry Caterpillar really just very hungry, or is it in the midst of an obsessive compulsive episode? Hephziba Anderson at the BBC writes about the hidden subtexts in children’s books – what’s really there, and what adults imagine is there.

Revisiting kids’ books in adulthood can yield all sorts of weird and wonderful subtexts, some more obvious than others. How could Dr Seuss’s How the Grinch Stole Christmas be anything other than a parable of consumerism? Why would it not seem blindingly clear that CS Lewis’s The Chronicles of Narnia are in fact a fantastical re-imagining of Christian theology?

Similar close readings have rendered the Paddington Bear books fables about immigration and Babar the Elephant an endorsement of French colonialism. Alice’s Wonderland adventures have been seen as everything from a paean to mathematical logic to a satire about the War of the Roses or a trippy caper with drugs as an underlying theme. And what about The Little Engine That Could? You might know it as a story about trains that fosters can-do optimism, but it has also been taken as a you-go-girl feminist tale. (The eponymous little engine is a lady train and when she breaks down, only another female train will stop to help out.) As for The Wonderful Wizard of Oz: why, it’s an allegorical representation of the debate surrounding late 19th Century US monetary policy, of course.

As adults, we can look at these books in their greater context. No longer just escpapist bedtime reading, even Dr. Suess gets real. This post at LilSugar runs down much of Suess’ subversive subtext, from environmentalism in The Lorax to anti-Semitism in The Sneetches. (See this 1998 story that NATO and the UN actually distributed The Sneetches to children in Bosnia in order to foster racial tolerance.)

Sometimes a train is just a train, though, and I have trouble getting worked up over a Soviet moral system in Thomas the Tank Engine. But as Anderson notes, even if children can’t identify them, larger, adult, themes can be an important part of a book’s charm.

When we pick these books up decades later, we’re surprised to learn what we doubtless always sensed as kids, even if we lacked the vocabulary to articulate it: that these stories are about eternal human strengths and weaknesses, about how to exist in the world.

Then again, the hidden nature of their messages is crucial to their magic. As Bettelheim noted, explaining to a child what makes a story so captivating would ruin it. Its power to enchant “depends to a considerable degree on the child’s not quite knowing why he is delighted by it”.

Julia Fleischaker is the director of marketing and publicity at Melville House.