December 12, 2012

This is your brain; this is your brain on books

by Ellie Robins

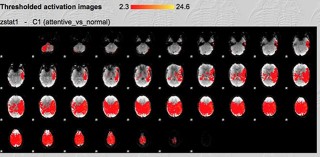

Blood flow to the brain while reading Jane Austen

Once we’ve all unwrapped our new Jabscreens this Christmas there’ll no doubt be another round of hand-wringing about what the internet is doing to our brains and will we ever create great art again and who will teach children to concentrate and oh god isn’t it all just so terrible? When that happens, try to remember this natty little piece of research.

Researcher Natalie Phillips noticed that writers were complaining about their wandering attention as far back as the Enlightenment:

Phillips warned against “adopting a kind of historical nostalgia, or assuming those of the 18th century were less distracted than we are today.” Many Enlightenment writers, Phillips noted, were concerned about how distracted readers were becoming “amidst the print-overload of 18th-century England.”

Rather than seeing the change from the 18th century to today as a historical progression toward increasing distraction, Phillips likes to think of attention in terms of “changing environmental, cultural and cognitive contexts: what someone’s used to, what they’re trying to pay attention to, where, how, when, for how long, etc.”

And set out to find a solution to the problem of the unruly attention span. Her findings have thrown out some amazing fMRI images of what happens to the brain when we read (see image above):

Surprising preliminary results reveal a dramatic and unexpected increase in blood flow to regions of the brain beyond those responsible for “executive function,” areas which would normally be associated with paying close attention to a task, such as reading, said Natalie Phillips, the literary scholar leading the project.

During a series of ongoing experiments, functional magnetic resonance images track blood flow in the brains of subjects as they read excerpts of a Jane Austen novel. Experiment participants are first asked to leisurely skim a passage as they might do in a bookstore, and then to read more closely, as they would while studying for an exam.

Phillips said the global increase in blood flow during close reading suggests that “paying attention to literary texts requires the coordination of multiple complex cognitive functions.” Blood flow also increased during pleasure reading, but in different areas of the brain. Phillips suggested that each style of reading may create distinct patterns in the brain that are “far more complex than just work and play.

As Phillips puts it, “it’s not only what we read — but thinking rigorously about it that’s of value, and that literary study provides a truly valuable exercise of people’s brains.”

Ellie Robins is an editor at Melville House. Previously, she was managing editor of Hesperus Press.