March 18, 2014

Walter Dean Myers and his son talk about race and children’s books

by Kirsten Reach

In the Sunday Times, YA author Walter Dean Myers and his son Christopher Myers, an illustrator, discussed the necessity of more diverse children’s books. A new study from the Cooperative Children’s Book Center of the University of Wisconsin says only 3% of books published last year featured black characters, and only 2% were by black writers.

In the Sunday Times, YA author Walter Dean Myers and his son Christopher Myers, an illustrator, discussed the necessity of more diverse children’s books. A new study from the Cooperative Children’s Book Center of the University of Wisconsin says only 3% of books published last year featured black characters, and only 2% were by black writers.

Why aren’t there more people of color in children’s literature? Christopher Myers said the closest thing to a villain he can find is The Market: “The Market, I am told, just doesn’t demand this kind of book, doesn’t want book covers to look this or that way, and so the representative from (insert major bookselling company here) has asked that we have only text on the book cover because white kids won’t buy a book with a black kid on the cover — or so The Market says, despite millions of music albums that are sold in just that way.”

Walter Dean Myers took a more personal tack, talking about empathizing with white characters as a young reader and growing frustrated with the absence of characters like him:

Then I read a story by James Baldwin: “Sonny’s Blues.” I didn’t love the story, but I was lifted by it, for it took place in Harlem, and it was a story concerned with black people like those I knew. By humanizing the people who were like me, Baldwin’s story also humanized me. The story gave me a permission that I didn’t know I needed, the permission to write about my own landscape, my own map.

During my only meeting with Baldwin, at City College, I blurted out to him what his story had done for me. “I know exactly what you mean,” he said. “I had to leave Harlem and the United States to search for who I was. Isn’t that a shame?”

…Books transmit values. They explore our common humanity. What is the message when some children are not represented in those books? Where are the future white personnel managers going to get their ideas of people of color? Where are the future white loan officers and future white politicians going to get their knowledge of people of color? Where are black children going to get a sense of who they are and what they can be?

Myers Sr. concludes that we would be more empathetic, and our justice system would be improved, if all young people had the opportunity to read about characters of color. Twitter users (led in part by Jennifer Weiner) began sharing their favorite titles about people of color with the hashtag #colormyshelf.

This isn’t the only instance of writers discussing the lack of diversity in publishing in recent memory, but it’s unusual to hear the focus on children’s literature. Lee & Low Books spoke with several authors and librarians about why there are so few multicultural children’s books. Interviewees suggested that there may not be enough diversity within publishing houses, or enough connections between writers of color and agents or publishers, or that the books that are put out are not marketed properly. These are the same issues that come up when we discuss the lack of diversity in literature for adults.

Dr. Sarah Park Dahlen, an assistant professor at St Catherine University, said one letter from a white male editor called a book by an Asian-American woman “exotic.” She found the adjective distasteful in this context. She writes, “Although not uniformly, I’m wary of non-Asian Americans who have written Asian American stories because I’ve read so many patronizing, Othering texts.”

In a lecture, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, who just won the NBCC Award for Americanah, said the first stories she wrote as a child in Nigeria were about white, blond, blue-eyed children who drank ginger beer, walked around in snow, and talked about the weather. She had never tasted ginger beer or experienced a snowy climate; she had been raised on children’s books from Britain and the U.S. She says that power lies in being the author of a definitive story about a place or a nation:

Power is the ability not just to tell the story of another person, but to make it the definitive story of that person…. I recently spoke at a university where a student told me that it was such a shame that Nigerian men were physical abusers like the father character in my novel. I told him that I had just read a novel called American Psycho, and that it was such a shame that young Americans were serial murderers. Now, obviously I said this in a fit of mild irritation.

But it would never have occurred to me to think that just because I had read a novel in which a character was a serial killer that he was somehow representative of all Americans. This is not because I am a better person than that student, but because of America’s cultural and economic power, I had many stories of America. I had read Tyler and Updike and Steinbeck and Gaitskill. I did not have a single story of America.

Jesmyn Ward, author of Salvage the Bones and The Men We Reaped, talked about race and publishing in her recent interview with Guernica:

Publishing companies put labels on these books. For me, the labels are Southern and black and woman. For some reason, they think an audience depends on the author’s identity, and every time they add another box, the audience gets smaller in their minds. You know those numbers showing that in the workplace, a person of color has to work ten times harder or more efficiently than a white colleague? I hate to say this, but I feel like that’s the case with literature, too. I’m not saying I have to write a book that’s ten times better than my counterparts, but I do think that I have to concentrate my efforts on writing something that will really engage people’s humanity and will tie readers to my characters regardless of race. I have to prove that I can connect with a wider audience. I think I accomplished that with Salvage. I went to Mystic, Connecticut, for example, to a wonderful bookstore there, full of people who couldn’t have been further from the place I come from, but they really responded to my work and saw my characters as human beings and loved them that way.

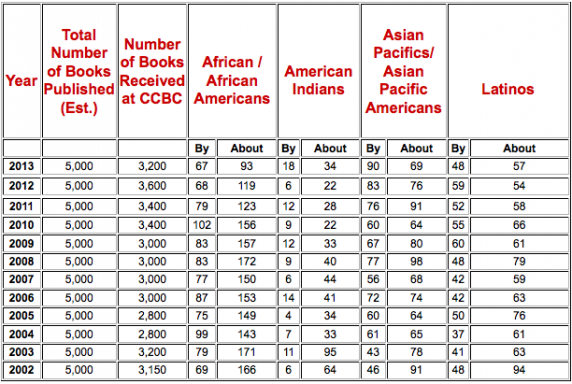

Finally, here are the number of children’s books by and about people of color since 2002, according to the CCBC:

Here’s an infographic from Lee & Low about the last eighteen years:

The numbers are terrible. Publishing is too white and privileged and short-sighted. We need to do better.

Is the issue that these stories are being written all the time, and publishers aren’t taking them on? Or are too few stories being written? It seems like a little of column A, a little of column B.

In yet another article about millennials last week, Reid Wilson reminded us that that generation is the most diverse generation. There is a population out there that could support a wider range of backgrounds in its characters or its authors. When will the diversity in the U.S. population be reflected in its literature?

We need educational programs that will encourage people to read and write. We need diverse writers with great stories. We need diverse stories by great writers. We need readers to pay attention to these stories. We need cool librarians, booksellers, teachers, and parents who will seek out books by multicultural writers, and who will spread the word about them.

Kirsten Reach is an editor at Melville House.