July 7, 2015

NME will be free! Britain’s most notorious music magazine embraces the Time Out model

by Mark Krotov

Why, as an adolescent, did I spend so much time reading NME, aka the New Musical Express, aka Great Britain’s most excitable, overheated, and temperamental music magazine? Perhaps because the spirit of the magazine was itself more than a little adolescent.

Why, as an adolescent, did I spend so much time reading NME, aka the New Musical Express, aka Great Britain’s most excitable, overheated, and temperamental music magazine? Perhaps because the spirit of the magazine was itself more than a little adolescent.

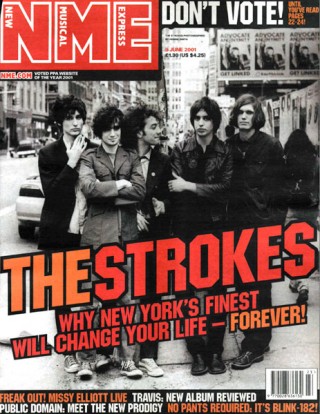

Unlike American music magazines, which seemed to hew to coolness and self-restraint even at their most earnest moments, NME was aggressively enthusiastic. A band no one had ever heard of would suddenly be proclaimed the Next Big Thing, and it would remain that way until some other band would take on the burden, and the previous Next Big Thing would be castigated.

In its heyday, which lasted decades, NME was influential, widely read, and controversial. The Guardian’s piece on the magazine’s latest transformation (more on that in a moment) offers only a hint of the impact of NME, which

has played a pivotal role in both the independent and mainstream music scenes over its six decades of publication.

Early readers of the magazine included John Lennon, Malcolm McLaren and T Rex frontman Marc Bolan, while its writers have included Bob Geldof and Pretenders lead singer Chrissie Hynde.

Yet even when I read it diligently, in the early 2000s, NME felt like something of a throwback. Websites like Pitchfork and Stereogum had captured (though did not replicate) the magazine’s energy, and a growing archipelago of music blogs proved to be as good as their printed antecedent at generating hype.

I write about NME in the past tense because I haven’t read the magazine in about a decade, which is unfair, but probably not inconsistent: there must be generations of ex-teenagers who lived through their own NME era, only to graduate into something more mature and less fun.

But the past tense might be appropriate for another reason: NME, which is down to a circulation of 15,000 from a peak of over 300,000 in 1964, is going to become a free magazine. As the Guardian reported yesterday:

The move, which has been rumoured for several months, is an attempt to navigate the torrid conditions of the consumer magazine market . . . From September, 300,000 copies of the magazine will be distributed free of charge in the hope it will boost advertising revenue and ensure its continued survival in print as well as online.

There are many reasons to be wary of this move; media industry analyst Douglas McCabe was interviewed by the Guardian and cites a few of them:

My instinct is to feel quite concerned about it . . . When you look at other magazines that have gone free, like Time Out, the reason they’ve been a great success was because they didn’t have to adapt very much. It was a magazine that readers already understood and already had broad cultural interest—whereas NME will have to work very hard to move away from becoming a niche interest title. So in my view they’ve built up a relatively challenging proposition.

We’ll have to wait until September to see what the new NME will look like—and whether its new model will allow it to preserve the things its many fans have cherished for generations. But as McCabe says, worry is not an inappropriate reaction. In a statement, the magazine’s editor, Mike Williams, said that

NME is already a major player and massive influencer in the music space, but with this transformation we’ll be bigger, stronger and more influential than ever before. Every media brand is on a journey into a digital future. That doesn’t mean leaving print behind, but it does mean that print has to change, so I’m incredibly excited by the role it will now play as part of the new NME. The future is an exciting place, and NME just kicked the door down.

Which doesn’t lack for enthusiasm, but it’s hard not to agree with the music critic Marcello Carlin, who tweeted the following in response to Williams’s statement:

“massive influencer in the music space”; I preferred it when NME editors spoke English.

— Marcello Carlin (@marcellocarlin) July 6, 2015

Indeed.

NME may very well be dead. Long live NME!

Mark Krotov is senior editor at Melville House.