June 10, 2011

Sherman Alexie takes Megan Cox Gurdon to task for her dumb essay

by Melville House

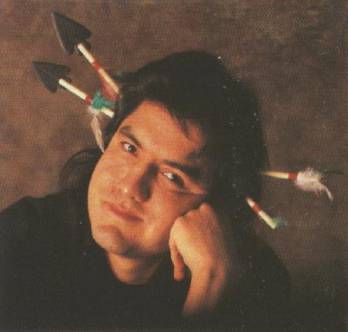

Sherman Alexie, champion of YA lit, warts and all

Perhaps Sarah Weinman said it best on her Twitter yesterday: “dear Meghan Cox Gurdon: the moment you say readers have written emails supporting your piece, it’s all over.”

Weinman of course was referring to the controversy sparked by Megan Cox Gurdon‘s condescending, churlish, and pedantic essay railing against the darker elements in modern YA fiction in last weekend’s Wall Street Journal, and linked to this interview Cox Gurdon gave to Karen Springen for Publishers Weekly in which she whines about being misunderstood. ”This is another great example of people supplying from their own fevered minds what I didn’t say,” she said. “There’s a big graph in the piece about the argument in favor of these books — that they are thought to validate the experience of teens who are suffering.”

Never mind that that graph precedes another in which she takes that argument apart and shits all over it, almost completely dismissing the notion that engaging with dark or disturbing content can be cathartic. But I digress.

In her piece, Cox Gurdon specifically singles out Sherman Alexie, the author of The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian, chastising him for defending the bleak and lurid in YA fiction when he said that much worse could be found on the internet. “One depravity does not justify another,” she scolded.

Thankfully, Alexie responded with his own essay in the Journal yesterday:

Almost every day, my mailbox is filled with handwritten letters from students-teens and pre-teens-who have read my YA book and loved it. I have yet to receive a letter from a child somehow debilitated by the domestic violence, drug abuse, racism, poverty, sexuality, and murder contained in my book. To the contrary, kids as young as ten have sent me autobiographical letters written in crayon, complete with drawings inspired by my book, that are just as dark, terrifying, and redemptive as anything I’ve ever read.

Alexie goes on to describe some pretty shocking details about his own childhood, being raped, being let down by the adults who were supposed to be looking out for him, and how he’d wished that as a child going through these things he’d had a book like his own that could have spoken to what he was experiencing. And then he takes Gurdon to task quite nicely:

When some cultural critics fret about the “ever-more-appalling” YA books, they aren’t trying to protect African-American teens forced to walk through metal detectors on their way into school. Or Mexican-American teens enduring the culturally schizophrenic life of being American citizens and the children of illegal immigrants. Or Native American teens growing up on Third World reservations. Or poor white kids trying to survive the meth-hazed trailer parks. They aren’t trying to protect the poor from poverty. Or victims from rapists.

No, they are simply trying to protect their privileged notions of what literature is and should be. They are trying to protect privileged children. Or the seemingly privileged.